A touch of light: whispers in pollen, amber and stone

14 October 2020

Archived article

By MIKE GILLAM

All photos © Mike Gillam

We walked in the shadow of the range for six hours, our path slowed by numerous gullies and channels that braid the gravelly foot-slopes. At each significant break in the range we detour and check for water before continuing our west to east transect.

In un-trampled places the soil exhibits a delicate crust of cryptogams, some are distinctly two-tone where the dry mesh of lichens, algae and bacteria is flushed with colour in response to a rain shower the day before.

The gorge ahead looks more substantial than those we’ve already checked; underfoot, the scatter of stone chips increases markedly. Here, a low mound where countless generations of patient men sat and experimented with varieties of stone, chipping and shaping their treasured cutting knives and larger implements.

Nearby the grinding stones show where women worked; one large base stone has several elliptical grinding grooves with a round reddish ‘pestle’ stone placed on top awaiting the return of its owner.

We rest a while to give my friend a break, he’s booked in for another hip replacement and his gait has a disturbing crab like quality that has me wincing in sympathy.

Thankfully the mulga staff is making a difference to his balance and confidence. There’s a lingering regret and concern for his safety also, but I know better than to give voice to my concerns.

We enter the gorge an hour before sundown and more petroglyphs appear almost immediately. There’s a large dry rock-hole and smaller features with limited water and some thriving ficus. A grey fantail flits ahead of us.

Lichen abstractions decorate the shady protected cliff faces and liverworts form pale silver and green curtains hanging like frozen waterfalls from moist fissures. In one overhang we find a large stone tabletop with strongly incised lines, a site where stone weapons were sharpened according to popular belief.

We complete our reccy and return to a sandy creek bed at the mouth of the gorge to make camp. The September weather is mild and we eat from our meagre supply of muesli bars, nuts and apples before finding an agreeable patch of sand to sleep. A lack of bedrolls is the price of travelling light and sleep is fitful but adequate.

We rise in the predawn and make preparations for the day. Heat the coffee and skip the rest. A breeze murmurs through the modest gorge as we enter; its high value to the original Arrernte inhabitants is expressed in long lasting rock-holes, galleries of petroglyphs and deep shade.

Some artworks may well record the earliest human responses to, and memories of, this place, its sacred sites, totems and animals.

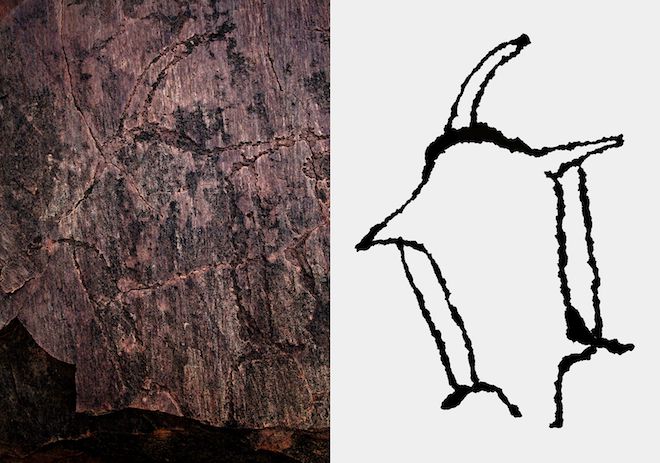

Among the carefully inscribed, chiseled and fretted markings I examined that day, was one of special interest. On a large flat rock, eroded over aeons, was the unmistakable outline of a marsupial glider. Yet another depicts a four fingered mammal track of unknown identity. Instinctively I search among the vertical rock splits and high ledges for signs of Leporillus apicalis, an elegant native rodent that builds elaborate nests, presumed extinct. The habitat looks promising but for the thousandth time there’s no sign.

The glider shape is very distinctive but eroded by the elements and somewhat confused by natural rock fractures. I curse my lighting oversight; there is no flash or torch to provide low angled light and accentuate the chiseled lines. Although the outline is imperfect, we can still clearly trace the curved tail at the top, the four outstretched legs with additional flaps of skin stretched between and the head at the bottom with its nose chipped away by a rock fall.

I suppose it’s still possible that this tiny marsupial persists in remote and well watered microclimates of inland Australia but more likely the petroglyph in question records a life form that vanished after the onset of aridity.

Petroglyphs at N’Dhala Gorge are estimated to be from 2,000 to 10,000 years old and I could well imagine sugar gliders inhabiting this place during the last pluvial. Who knows, perhaps they still exist in remote topographic wonders, of fire shadows and vertical retreats, niches that give the native a rare advantage and make life difficult for predatory cats.

Libraries of ochre cave art and petroglyphs are extensive and yet they don’t tell the full story of Aboriginal knowledge of a changing landscape before Centralia was settled by Europeans from the late 1880s.

Libraries of ochre cave art and petroglyphs are extensive and yet they don’t tell the full story of Aboriginal knowledge of a changing landscape before Centralia was settled by Europeans from the late 1880s.

Leading archeologist Dr Mike Smith has studied human occupation of the Australian arid zone over several decades. He presents a complicated and fascinating picture: of human resilience and land use through glacials and interglacials, responses to the onset of aridity with retraction of the summer monsoon (most severe between 24-20 ka, and with rising temperatures at 17-16 ka) and then the re-establishment of the summer monsoon after 16-14 ka.

The fossil record as revealed by palaeontologist Dr Peter Murray and colleagues illustrates another world entirely, from vast inland lakes inhabited by crocodiles and flamingoes, of marsupial lions, diprotodon and ancestral kangaroos.

There is some conjecture about the overlap between humans and the megafauna; examples of dated Pleistocene cave art are quite limited and their antiquity is often contested.

However, it is clear from recent research at Warrtyi in the Flinders Ranges that humans occupied the arid zone at 49 ka and indeed hunted megafauna. This should add weight to some of the contested examples of megafauna depicted at art sites.

Unambiguous thylacine petroglyphs depict a species that became extinct much more recently, likely displaced by dingoes that arrived on the Australian mainland from South East Asia about 5000 years ago. I have no idea of the age of the glider petroglyph but the species may have declined or disappeared as a result of changes in rainfall and climate, well before the arrival of Europeans and their cargo of rabbits, cats and foxes.

More information, albeit scant and sometimes hard to find, is recorded in the post contact period by explorers, pioneers, visiting scientists and writers:

…A local resident [surely Telegraph employee P.M.Byrne] recorded that rabbits first appeared in numbers near Charlotte Waters the year after the Horn [Scientific Expedition in 1894] … and that by 1921, ‘the rabbits have supplanted the marsupials.’… (So Much That Is New, Mulvaney & Calaby’s biography of Baldwin Spencer 1860-1929.)

There is overwhelming logic and research underpinning the notion that the rabbit invasion was followed by predatory cats and foxes: “Cats did not occupy Australia from the earliest point of entry (Sydney, 1788), but instead diffused and were spread from multiple coastal introductions in the period 1824–86. By 1890 nearly all of the continent had been colonised…”

Another scenario based on popular anecdotal evidence was repeated by several early writers and noteworthy researchers of the times. This view held that cats came to the interior much earlier, from the west coast and before the European settlers; presumably originating from whaling vessels or even Dutch shipwrecks. A passage from the classic I saw a strange land by Arthur Groom is representative of the prevailing and persistent view of the times.

Groom, author and travel writer came to Central Australia in 1946 and employed Aboriginal people as guides and camel handlers to assist his travels across more difficult terrain. At the time Groom and his companions, periodically distracted by Government rewards offered for dingo scalps, were travelling south of Watarrka, the George Gill Range.

Tiger, one of his more experienced Aboriginal companions, revealed:

…wild dawg – been here alla time. Horse and cattle come before rabbit. Pussy-cat he come long, long time ago – before sheepee an’ bullock an’ camella. My people tell me – pussy-cat come that way,” he nodded to the west. “Long time ago – before white people come, big boat come that way and pussy-cat jump off, run about, find ‘nother pussy-cat, and now big mob pussy-cat everywhere, run about desert country alla time; eat little birds – lizard – eat close up everything.

Whatever the pattern of invasion, at Finke Gorge National Park, it seems likely the arrival of cats was to spell disaster for Leporillus apicalis, the lesser stick nest rat or white-tipped stick nest rat. A communal species, it lived in elaborately constructed nests in rocky overhangs, often integrating natural crevices, ledges and vertical chimneys. One huge nest measured in South Australia was estimated to be 3 x 2 x 1 metre.

Whatever the pattern of invasion, at Finke Gorge National Park, it seems likely the arrival of cats was to spell disaster for Leporillus apicalis, the lesser stick nest rat or white-tipped stick nest rat. A communal species, it lived in elaborately constructed nests in rocky overhangs, often integrating natural crevices, ledges and vertical chimneys. One huge nest measured in South Australia was estimated to be 3 x 2 x 1 metre.

The last confirmed sighting of Leporillus was in 1933 and the species, once widespread in Central Australia, was considered extinct by 1940 following thirty years of steady decline. Largely absent from the literature and rock art, Leporillus has left its own distinctive signature in the rocks; a residue called amber rat, deposits of a tar like substance, hardened and varnished, mark the communal toilet sites close to the elaborate nest structures.

It’s still possible to find relatively intact stick nest structures in crevices and beneath rocky overhangs in the weather protected sites favoured by these impressive nest builders. I always check to see if new material has been added to the nests, ever hopeful that miracle populations might persist somewhere in the high country.

It’s heartening to remember that another native rodent, Zyzomys pedunculatus, believed to be extinct for over fifty years was re-discovered in 1997 in the west MacDonnell Ranges. As I scan the latest cohort of dead Callitris pines west of Alice Springs I wonder how the reprieved Zyzomys is doing. At Standley Chasm a great many cycads are also charred, their life force frozen like blackened steel sculptures and yet I know that unlike the pines, new growth will likely follow.

Undoubtedly the cats and foxes followed the rabbit invasion of Central Australia but there was an earlier introduction at Palm Valley in the Finke Gorge National Park that fooled scientists for a while. The landscape of cross bedded sandstone, wet gullies and tall graceful Livistona palms has a primeval quality. Ancient cycads and Callitris pines are delightful features of the deep magenta and lichen streaked rock walls and complete the perfect picture of a botanical time trap.

Only recently was serious doubt cast on the antiquity of Central Australia’s most famous oasis. Cycads and pines occur widely throughout the high country but the Livistona palms occur nowhere else in this region.

Clearly we have grossly underestimated the movement of trade items and knowledge between Aboriginal language groups in Australia. DNA evidence has proven that custodians of this remarkable place secured the seed of palms from the far north and planted them to enhance their own country.

Clearly we have grossly underestimated the movement of trade items and knowledge between Aboriginal language groups in Australia. DNA evidence has proven that custodians of this remarkable place secured the seed of palms from the far north and planted them to enhance their own country.

It seems likely that the seed was either traded or brought down from the north by the original Aboriginal explorers who travelled to the site during climatic conditions more favourable than the present day:

…the red cabbage palm, as it’s known locally, came via seeds somehow carried south nearly 1000 kilometres from palms that grow in the north. Now new evidence from a group of Australian and Japanese researchers shows that the red cabbage palm has been diverging from its northern parents for just 15,000 to 30,000 years…

Most of Finke Gorge National park has been spared from fire for decades now, a result of continuing and massive investment by ranger staff who undertake regular control burns during winter and manage fuel loads by a variety of means.

One frosty morning I watched the pollen puff from a hillside of native Callitris pines, a line of seven or eight trees, one after the other, casting their magical smoke as an unseen zephyr flowed across the hillside. The scene backlit by the rising sun was at once slow and yet deceptively fast. There was little point running for the camera, sensibly I enjoyed the choreography of the moment.

Kieran and Mike,

Thank you for interpreting the country for us.

Another fascinating piece – thanks!

Love this series.

More wonder.