A painter’s painter turns her eye on Hermannsburg

11 September 2020

By KIERAN FINNANE

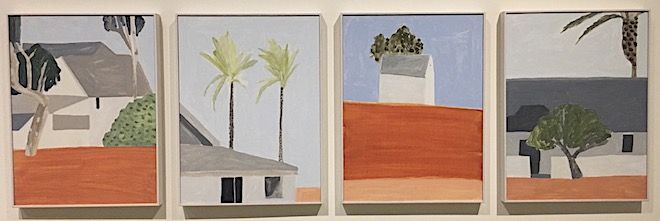

On entering the gallery showing Neridah Stockley’s Hermannsburg & Paint there is an impression of a lost city, laid bare by a receding sea or sands. It is a low-rise city, of flat white walls detaching themselves from patches of grey and black shadow, of powdery blue sky and bright white light. Small structures cluster on the walls and on the plinths as if separated from one another by scoured sands. A city – waiting to be put back together again.

This impression is undone at closer inspection, but it makes a point about where Stockley’s focus is in this show that grew out of a creative residency she undertook in 2019-20. As she writes in her artist statement, the show is framed around three paintings by Albert Namatjira held in the Araluen Art Collection, but it had its roots in a much earlier aesthetic engagement with “the layered Hermannsburg Precinct”.

Only one of the three Namatjira paintings shows the precinct, Hermannsburg Mission with Mount Hermannsburg, 1937. In this work the mission buildings occupy a narrow band that takes up perhaps one-tenth of the painted surface, with the mountain of the title looming above them like a sleeping giant.

In a second Namatjira painting, Albert’s Camp near Mount Hermannsburg, 1941, a tiny tent can be seen in the middle ground, again dwarfed by the mountain and the mighty landscape in which it sits.

Stockley has clearly responded to the mountain, its impressive presence and scale, in the oil on paper works, 71, 72, 89 (pictured below). As your eye becomes accustomed to her degrees of abstraction, you then discern it in multiple works, attenuated, another form among forms and less preoccupying for the artist than the human-made forms of the mission buildings – essentially, elaborated tents – and their contents.

These forms are mostly stripped down to their rough geometric essence; perspectives are flattened; textures, lights and darks are schematised; verisimilitude is minimal –qualities all found, unusually, in the third Namatjira painting she chose, Ghost Gum, West MacDonnell Ranges, c 1938. It is a painter’s painting, deeply involved with a visual experiment, while also powerfully meditative.

Stockley, one of the Centre’s best known non-Indigenous artists, with a national profile, is a painter’s painter. Her primary interest in this show – and long-standing – is in ways of seeing, but her rigorous attention also distills something important about what the Hermannsburg Precinct represents.

Most viewers will know, from what they bring with them, that Hermannsburg has a bicultural or transcultural history. In this show Namatjira’s rendering of the mission buildings, of his tent, though puny in the scale of Country, signal the colonial wave breaking upon the Western Aranda world. The fact of his painting, and of his achievement in painting, signal the Aranda’s withstanding force, what they made of the extraordinary change.

For Europeans this country has been perceived as empty without the material structures of habitation and cultivation. Being a viewer of European heritage, my eye, for example, in these two Namatjira works is immediately riveted by the human-made forms; though tiny in scale they compete with or out-compete the grand natural structures for my attention. Stockley’s whole show – 128 works – can be considered as an extended exposition on this way of seeing.

It makes sense of that ‘lost city’ impression I had on first entry – the ‘civilising’ city standing behind the mission project fractured in these desert sands even as it fractured also the old Aranda world.

In the ceramic works – beautifully executed, and this is a recently-acquired skill – Stockley sometimes homes in on detail, recognisable vintage objects, typographies, scraps of hand-written text, no doubt drawing on artefacts preserved at the precinct. In some, she also renders homage to a mark-making of the era, needlework, the province of women (taught to the Aranda women by the missionaries’ wives). Though many others register the same preoccupations with the basic forms of European-style shelter as do the paintings, all the elements are the relics of the mission project.

At times in the paintings the artist softens the rigour of her approach to do more representational work. As the images from the whole show settle in my mind, these become the least representational of the precinct. They have the allure of a Mediterranean village – the romance of what some visitors to the precinct no doubt are looking for, as an experience and as a history.

The march around the gallery of Stockley’s stripped-down forms in a reduced palette registers a more challenging view.

Shows at Araluen until 8 November.