Loading article…

Loading article…

18 August 2020

By MIKE GILLAM

All photos © Mike Gillam

I look at a map of major aquifers in central Australia variously named Ngalia, Amadeus, Lake Eyre, their boundaries delineated and mapped in reassuring detail, parts of which are now overlaid by gas exploration leases that leave no gaps in between.

I’ve barely scratched the surface of this country but I know of secret places with water features, the kind that aren’t mapped and delineated. Sandstone gorges with unique petroglyphs and aquatic macro-invertebrates still waiting to be discovered.

My camera captures the gyrating motion of whirlygig beetles that move so quickly they displace water, leaving visible tubes in their wake (image second from bottom). Water striders gather, like hyenas at a carcass on the African Plain, around the discarded head of a grasshopper.

River channels with deep pools reveal their secrets at night; primitive transparent prawns with impossibly long forelimbs, a curious purple spotted gudgeon, desert gobies and eel-tailed catfish swim slowly through the torchlight.

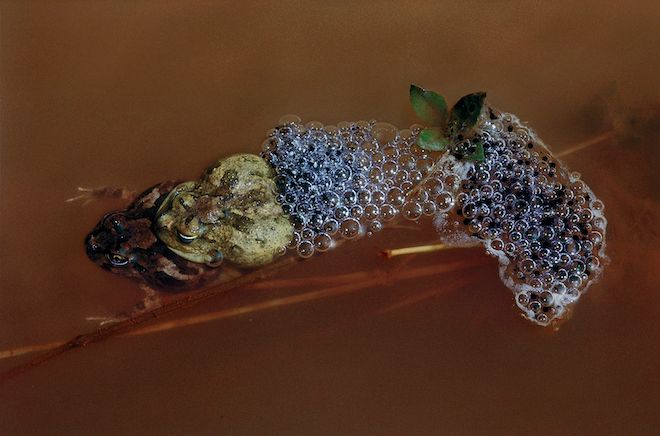

Here’s the riverine burrowing frog, Opisthodon spenceri, that comes to the surface to hunt insects and vanishes beneath the sand at sunrise. They live in the sandy margins of the river channel pools and keep hydrated by following the subtle movements of the water table; year after year, centimetre by centimetre, as they wait for a summer flow of the river and a chance to breed (image at bottom).

To survive and prosper in the semi-arid and arid lands of Centralia, Aboriginal people needed an encyclopaedic knowledge of their country, especially water sources, their lifeline in good seasons and drought. Even today their knowledge at a local level collectively surpasses and is much more nuanced than the broad brush mapping of water resources by Government.

The Arrernte dictionary, published by IAD Press, lists well over 40 conditions, types and actions of water. For example, kwatye-kwerte, meaning misty rain, combines the words for water and smoke. Brown water from fallen leaves and bark tannins is unerre. Froth on running water in creeks is antye and damp earth is terte.

Not surprisingly it was the permanent surface waters that were most valued. For every Aboriginal person these rare places were the most revered, most protected and sacred features of their country.

With the arrival of Europeans, water places became flashpoints of conflict and more often great anguish, as people were driven off or helplessly watched as their sacred sites were damaged by herds of livestock.

During the outstation movement from the 1970s to the present day, remote communities and homelands were often established at or near the beloved wells or permanent pools inhabited by rainbow serpents, those powerful ancestors from the age of creation.

One such carpet snake ancestor connects the Todd River south of Ntaripe (Heavitree Gap) at Alice Springs with the sacred rockhole at Arurlte Artwatye (Native Gap) 115 km north of the town and the waterhole at Glen Helen 150 km to the south-west.

This site is located in the Hann Range, a sandstone ridge overlaying basement rock and situated in the Ngalia Basin, a place of remarkable subterranean diving beetles. (This is a new frontier for scientists and many new stygobitic (living exclusively in groundwater) life-forms are being found and described.)

Elements of the carpet snake creation story shared by Arrernte and Anmatyerr people are described at the Arurlte Artwatye reserve.

“A giant carpet snake ancestor came out of the small waterhole. Before leaving he sang a song which was so full of feeling that the throats of the young maidens felt as if they were tightly bound with grass… Again he sang and once again the young women were Witchelka – choked with emotion and love.

“His song complete, the great snake rested his head on the range. Then he went up into the sky to return to earth at the Glen Helen waterhole, 150 km in the south-west. In the form of a man he then walked back…to Native Gap where he remains today.”

The map within this story highlights the value and paucity of permanent waters, the movement of people between them and the importance of song-lines connecting country and language groups. While knowledge of this nature might be widely shared, one person was unlikely to be the repository of it all.

So it was that I was shown a site many years ago, a place that people were worried for, a place that unthinking people might damage in the bed of Lhere Mparntwe (the Todd River ), south of Ntaripe. The site was identified by the Medusa-like roots of an ancient gum in the river bed, carefully covered up with sand. From there I was given sparing details of a snake that rose up into the sky and flew north to the rockhole at Arurlte Artwatye.

Underground aquifers feature prominently in popular film culture, much of it borrowed from the United States, gritty and gilded stories of pioneering triumphs over adversity. Everyone is familiar with the scene of well diggers using dynamite in final desperation and the satisfying geyser of water shooting skywards under pressure.

Less familiar is the 1880 account of workers on the Overland Telegraph Line who blasted a ‘native well’, very likely a permanent source of water, a rockhole, in an attempt to make the supply bigger and better. The site of this disaster resulted in the loss of the water-holding feature at Arurlte Artwarte: the water drained away.

I daresay such acts greatly eroded trust in European government and belief in the ingenuity of western technology. There’s every indication that little has changed in the intervening 100 years except perhaps the loss of trust in government has by now permeated more widely, especially on matters of the environment and the role of corporations.

In Centralia the precarious availability of surface waters led to the pastoral industry’s ambitious industrialisation of subsurface resources. The water story gathered pace in the decades following World War II with widespread drilling for groundwater. The rangelands were finally conquered with windmills and the tyranny and authority of climate was gradually silenced for a time.

This allowed pastoralists to graze more stock, much more widely, with the support of frequently placed windmills that pumped water to surface tanks and troughs. We will never know how many rockholes, how many fragile seepages and relict species were lost as water tables lowered and the supply to natural features ceased or slowed.

Natural surface waters and the surrounding lands bore the brunt of grazing in the early days but the creation of numerous permanent waters throughout Centralia enabled vastly more country to be exploited without pause.

Today there are around 35,000 known water bores in the Northern Territory. I’d suggest that our society understood precious little of what was risked and ultimately lost during pastoralism’s industrialisation of water.

Now the industrialisation of water in Centralia’s rangelands has entered a new phase of escalation, extraction and grazing intensity but there will be no independent review of the environmental costs. Kilometres of poly pipes are being laid across the land so that cattle may fully and constantly reach every last fertile corner that was not previously supported by permanent water.

With huge evaporation rates in excess of two metres per annum and an annual rainfall of less than 300 mm, permanent waterholes such as Glen Helen and Boggy Hole are invariably sustained through a connection with subsurface aquifers.

In a handful of rare places located in the Chewings and George Gill Ranges, water trapped within layers of rock and released gradually through fractures result in continuous, albeit minor, stream flow. These relict streams persist on the surface over relatively short distances and usually overflow into a permanent water source. The importance of these rare freshwater environments were highlighted by ecologist Jenny Davis who has led associated research and survey efforts in Centralia since 1993.

Among the notable discoveries was the presence of the water penny, Sclerocyphon fuscus, a species also known from temperate south-eastern Australia.

Unlike whirlygig beetles that readily take to the air to disperse, the water penny beetle that Davis describes is a life-form of low vagility (its spread within an environment). Larvae are usually found in riffle environments, in exceptionally clean water attached to rocks. Clustered individuals have given rise to the common name of leopard rock and adults, while terrestrial, are unable to fly.

I’m certainly convinced by the insights of Dr Davis in her evidence provided to the Northern Territory fracking enquiry. “…As my previous research has shown, water resources are vital refuges in dry landscapes. Some subterranean aquifers and mound springs supported by the underground waters of the Great Artesian Basin are “evolutionary refugia”, supporting species that have persisted for up to a million years and which live nowhere else on earth.

“Springs in the Central Ranges support relict populations of aquatic insect species, such as mayflies, caddisflies and waterpennies, that were once more widespread but became isolated as the continent became increasingly dry.

“Groundwater-fed springs across the Outback are likely to be important refuges in the future because they are mostly decoupled from regional rainfall. However, if springs are polluted or allowed to dry completely, extinctions will occur because the specialised species they support cannot easily disperse to live somewhere else…”

And I could not pass up this cautionary quote from RMIT’s Dr Gavin Mudd in his evidence to the fracking enquiry: “The constant emphasis on risks being low and manageable just shows too much confidence,” he said. “We need to be much more realistic and mindful of examples [of contamination] like PFAS, like McArthur River Mine, Rum Jungle and Red Bank Copper Mine.”

Like Dr Mudd, I want to know when the pro fracking Federal and Territory Governments intend to clean up the Rum Jungle uranium sites, dating back to the 1950s and described as one of the most polluted sites in Australia.

At the time of writing, an election looms in the Northern Territory and the subject of ‘fracking’ and the promised gas boom is at the forefront of many voters’ minds. Setting aside for a moment the Federal Government’s egregious role in pressuring the Northern Territory to embrace fracking and admitting my own limitations in analysing this complex issue, I do understand a few things.

Fracking represents another huge potential drain on artesian water and added risks of pollution by this water intensive industry.

A number of major fracking companies in the US have recently filed for bankruptcy and a huge number of uncapped wells with climate-wrecking potential will presumably be left for the taxpayer to remediate. Will rogue emissions be ignored by politicians for decades to come?

A recent article published in the New York Times makes me shudder. “The federal government estimates that there are already more than three million abandoned oil and gas wells across the United States, two million of which are unplugged, releasing the methane equivalent of the annual emissions from more than 1.5 million cars.”

In the right hands, mining technology can operate with a high regard for environmental safety although I’ve seen first hand the shocking disregard for sacred sites by profit-driven miners. I also know as an absolute truth that the Northern Territory Government does not have high standards when it comes to compliance. In terms of proactive environmental enforcement they are generally missing in action and the consequences of taking action after the fact don’t bear thinking about.

So I say, Vote (1) artesian diving beetle!

Thank you Mike. Every time I read your articles I think of a great man: Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, German poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, statesman, theatre director, critic, and amateur artist. He was not a photographer because the technology was not here!

You are a wonderful stories teller, lover of nature and a great teacher.

Thanks for taking us with you on this wonderful exploration. And also, as always bringing the big issues to light. It’s sobering to think what water may have existed here prior pastoralism.

Protect water. Ban Fracking.

What a wake up call this telling and timely short history of Territory water. I turn on the bathroom and kitchen tap, water the veggie garden and ignore its source. At my peril.

As with your previous elucidating notes, you give it right scale; the minuscule embattled beetle pitched against pastoral and mining interests.

This is water. As fundamental matter as the air we breath. I second your vote.

The logic of capitalism has always escaped me. Infinite growth with finite resources.

Energy now but no drinkable water tomorrow. There is something very very wrong with the world.

We don’t seem to be smarter than yeast.

Great article Mike, thanks for writing it. Thanks Alice Springs News for publishing it. It needs to travel far, especially to Darwin readers.

Plans to frack the NT beggar belief. And on this occasion I don’t mind the auto spell genie, just tried to change my text to “crack the NT”. I’ll do my best to share widely. Cheers Lisa.

Historically greed has overwhelmed what should be common sense.

Our personal wellbeing relies wholly on our environment.

Take away our unpolluted water, air and food source and you get what is happening in so many places across our world with an increase in cancers, and other life threatening diseases.

The COVID crisis has shown many around the world, especially in the most air polluted environments, we can survive without all the pollution by adjusting our lifestyles.

Is it going to take a life threatening situation to finally wake people up? I totally believe fracking is not worth the risk.

It only needs one mistake and it could make our land uninhabitable. Once the water is contaminated there is no second chance. That has already been proven by past mistakes in all the risky ventures.

There are areas of our earth so polluted humans cannot enter, hidden away by governments that should be looking after their citizens well being instead risking everything for short term profit.

It takes one major fracking mistake and we lose our towns, communities, pastoral, farming livelihoods – the lot.

That is bad enough but where do we go from here? To the overpopulated, polluted cities we escaped in the first place.

I personally voted independent simply because the major parties have rarely listened to the public once elected. I lost faith in our system a long time ago.

Wake up people. Good health is the most important thing in our life, especially communities relying on under ground water for survival which is the whole centre of Australia.

For the risk takers, ask yourself who gains from your risk? It will not be you it will be another country or a business based away from where we live so you risk your whole well being for no real personal gain to make whomever wealthy.

Are you really that silly? Wake up before it is too late.

What a great article. Rainwater? We had 45,000 litres stored and don’t need either fracking or town water except in an emergency.

Yet we still pay the supply charge.

Let’s start with the real estate industry and developers. An anecdotal report from friends in Sydney in the development industry describes how developers and planners in Sydney are forgoing rainwater storage facilities in favour of carports because the yield in $ per square metre is more on carports that on water storage facilities.

So we let the rainwater flow down the drain, and concentrate on carports.

And what could be more absurd in an arid region such as we have than to go to great expense to pump fossil water to the surface, use it to flush away human waste and then treat it as a waste product (including the nutrients that it contains) and let it evaporate.

Look at the market gardens North of Adelaide and ask how they get their water and nutrients.

Israel can produce a ton of potable water for just under 60 cents and Israel has an export industry in irrigation technology worth billions.

The technology is there.

Like so many other areas we refuse to open our eyes and look around.

Ps.: Mike, what happened to all the owls we used to have?

Trevor, I think you’re right to be concerned about owls but I can’t really shed any light on the matter.

Without any scientific evidence to validate my instincts, I feel that barn and boobook owls are probably naturally low in population density.

They are highly dependent on deep shade and old growth trees and these are being lost to fire and the ambitions of unit developers who are taking out mature Eucalypts on big blocks so they can redevelop for medium density units.

Every “habitat tree” counts and we are losing them regularly with virtually no hope of replacement.

Decorative Mediterranean gardens are increasingly popular with humans but rejected by urban wildlife en masse.

I recall more barn owls in the mid seventies but these were very wet years and the introduced house mice, Mus musculus, was periodically abundant.

I even recall trapping the long haired “plague” rat, Rattus villosissimus, in reasonable numbers at Bassos Farm on Charles Creek in 1975 or 76. So maybe owl numbers fluctuate with the availability of prey.

In the past decade I’ve seen barn owls only four times within the town area and two of these were dead.

I photographed one dead bird in the Todd River near the Schwartz Crescent causeway the day after Territory fireworks and another beneath an electrical transformer in Hele Crescent.

This particular transformer had fried several galahs over the years but the sight of a barn owl spurred me into action.

Thankfully I found a senior bureaucrat at PAWA who visited the site, understood that owls were precious and conceded that the transformer was very old and an upgrade was due.

True to his word the transformer was replaced a year later and there have been no more deaths in the eight years since.

We used to hear boobooks around town quite regularly and I photographed a trio of gorgeous babies in old Eastside about five years ago but I’ve seen none in town since.

Once again the importance of deep shade can’t be over-emphasised.

Lastly, our tragic use of commercial baits to poison mice is probably a factor and I’m certain they take a toll on nocturnal raptors.

After three years of severe drought the owls are clearly struggling and changes in the behaviour of people are critical.

@ Mike Gillam (28 August 2020 At 6:54 pm): Mike and Trevor, I’m pleased to report that boobook owls are present in the Todd River in the vicinity of the town centre as I hear one or two calling each night, sometimes in the evening or in the early hours of the morning if I happen to be up at that time.

I saw one recently when walking along the east bank of the river opposite the CBD at about 9pm – the bird’s calling led me to where it was perched on a low branch of a river red gum and I was able to see it quite well with the aid of a small torch.

A few weeks ago I was caretaking a property on Heffernan Road when one evening I heard a soft thud against the front screen door.

Upon checking I found a boobook owl perched a couple of metres away on a pot plant stand, where it stayed most cooperatively while I fetched my camera and took a few photos.

Presumably the owl had scored itself an insect on the screen attracted to the light.

Given conditions remain very dry and we’ve just been through winter, I’ve been a little surprised by the activity of these birds but obviously some are finding enough to get by on in and around the vicinity of town.