Zachary Rolfe: What evidence will be relevant?

14 August 2020

Archived article

By KIERAN FINNANE

What permission did police have to enter the premises in Yuendumu where Kumanjayi Walker was on the night of 9 November 2019, when he was allegedly fatally shot by Constable Zachary Rolfe?

What knowledge did police have of Kumanjayi Walker being predisposed to violence?

Who gave the officers permission to enter the premises?

What powers were they relying on for entry? And what was their plan?

What briefings had they had – for instance on the likelihood of Kumanjayi Walker resisting arrest and deploying a weapon?

These are some of the topics that defence counsel will seek to cover in the cross-examination of witnesses in the upcoming committal hearing of the case.

Mr Rolfe is pleading not guilty to the charge of murder.

His committal in the Local Court is a preliminary hearing of evidence upon which the court will base its decision on whether that evidence is sufficient to allow the matter should proceed to trial in the Supreme Court.

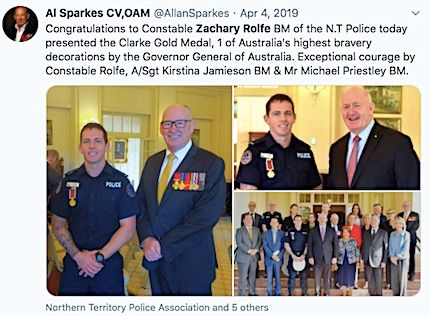

Mr Rolfe, decorated for bravery in 2019 (above), attended by phone last Friday’s hearing by Judge John Birch of argument between defence and prosecution counsel over the relevance of the topics and of the cross-examination of specific witnesses in relation to them.

Mr Rolfe, decorated for bravery in 2019 (above), attended by phone last Friday’s hearing by Judge John Birch of argument between defence and prosecution counsel over the relevance of the topics and of the cross-examination of specific witnesses in relation to them.

Relevant to whether Kumanjayi Walker was predisposed to violence, argued defence counsel, David Edwardson QC, would be evidence around an incident on 6 November, when the deceased confronted with an axe other officers attempting to arrest him.

What was the extent of Mr Rolfe’s knowledge of this incident on the night of the fatal shooting?

For the prosecution, Philip Strickland SC accepted that these topics were relevant but had arguments about the extent to which certain witnesses could give evidence on them. Hearsay evidence, for instance, would not be admissible at trial. Witnesses would have to have direct knowledge of events and briefings.

“Highly relevant”, argued Mr Edwardson, would be the evidence of the police officer who briefed Mr Rolfe about approaching Kumanjayi Walker on 9 November. What was her understanding, for instance, of what was expected of a police officer confronted by a person wielding a “blade” as, he said, was the case that night?

Mr Strickland objected to the relevance of this line of questioning of this particular witness.

There were no doctors or nurses in the community on the fateful night, as they had evacuated following the earlier “ransacking” of the clinic. Was Kumanjayi Walker involved in that earlier incident? If so, that could be relevant to his “state of mind” in seeking to avoid arrest on 9 November, argued Mr Edwardson.

Mr Strickland, however, said “intelligence” received on that topic by the officer briefing Mr Rolfe would again only be hearsay and not admissible at trial. It amounted to a “fishing expedition”, he argued, and in any case his involvement in the clinic incident would not be relevant at trial.

Mr Edwardson, however, countered that the defence was entitled to explore the issue, about which the present brief provides no information.

There was significant difference of opinion about expert evidence from medical doctors on the potential of serious or fatal injury being caused by a pair of scissors. Could scissors, for instance, have potentially cut the carotid artery? Part of that evidence would go to the mobility of the right arm of the deceased at the time of the scissors being wielded.

Mr Strickland objected that the witnesses do not have “specialised knowledge” of the underlying facts of the incident. To have an “expert opinion” on the matter they would have to know whether Kumanjayi Walker’s arm was “pinned down” by the third party (the second police officer present). That was a factual matter for the (eventual) jury to determine.

The medical doctors therefore could offer opinion evidence, rather than give expert testimony on this topic, he argued.

However, Mr Edwardson said one of the medical doctors, a burns and trauma surgeon with military experience in Iraq and Afghanistan, had viewed the body-worn camera footage of the incident. His evidence would thus be more than opinion.

Judge Birch will make his determination on the issues this Thursday, 20 August at 9am.

He extended Mr Rolfe’s bail to 1 September, the first day of the committal hearing, and gave him permission to attend from Canberra by audio-visual link.

The primary reason for this, said Judge Birch is the biosecurity concern (the Covid-19 pandemic) that all of Australia faces. He did not expound on what the secondary reason might be.

Mr Edwardson and Mr Strickland, today appearing from Adelaide and Sydney respectively , will appear in person in Alice Springs for the committal.

Meanwhile, the Warlpiri Parumpurru (Justice) Committee have appealed to the community to gather outside the court on the first day of the committal “in solidarity, support and love for one another”, as Kumanjayi Walker’s cousin Samara Fernandez-Brown (above) put it in a video callout on their social media.

She asked Aboriginal organisations in particular to lend support to Yuendumu families wanting to come into Alice Springs.

She did not comment on Mr Rolfe being allowed to appear at the committal by video link.

The most relevant question to ask in this case is whether the best interests of justice can be guaranteed by trial by jury or trial by judge alone.