Watercolour painting: learning from the best, one click away

14 August 2020

By KIERAN FINNANE

It was a case of watch and emulate: two of the top painters from the ‘Hermannsburg School’, working in the tradition of Australia’s most famed watercolour landscape painter, Albert Namatjira, were leading a masterclass.

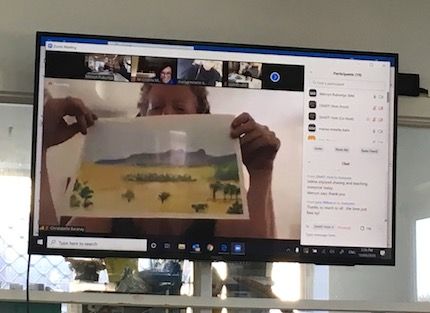

Selma Coulthard and Mervyn Rubuntja were settled at one of the painting tables in the studio of their art centre, Iltja Ntjarra Many Hands, in Alice Springs. The participants were scattered around the country, in cities from Melbourne to Darwin, small towns like Winton in western Queensland, and remote communities, like Fitzroy Crossing, all connecting to the Many Hands studio via Zoom.

The class was being hosted by the Darwin Aboriginal Art Fair (DAAF), which in this pandemic year has been conducted entirely online. Audiences have responded: all of their masterclasses, for instance, sold out well in advance.

The Many Hands lesson was simple but effective: the artists and participants started by drawing from a photograph of Mount Sonder / Rutjipma, a simple outline. Some simpler than others, mostly homing in on the large forms, the great sleeping mountain, the sky above, the open plain in the foreground, more so than the scattered vegetation and smaller rock formations.

The Many Hands lesson was simple but effective: the artists and participants started by drawing from a photograph of Mount Sonder / Rutjipma, a simple outline. Some simpler than others, mostly homing in on the large forms, the great sleeping mountain, the sky above, the open plain in the foreground, more so than the scattered vegetation and smaller rock formations.

The artists drew in some of the finer detail, but they were selective. This was about image-making, not reproduction of the photograph, and about expression also of their belonging to that country, made iconic by the Hermannsburg painting tradition.

The participants took their cue: when they showed their images at the end, they were remarkably varied in approach, just as Coulthard and Rubuntja’s paintings were quite distinct from one another.

Staff in the studio filmed as the artists progressed – laying down their first washes, building up colour, depth and detail.

Coulthard mixed her own colours, as she had been taught, creating a greyish green for the vegetation, closer to the way she sees it when she’s out bush. She understood that Albert had worked from just three basic colours, blue, red and yellow, mixing them himself for the other hues.

During quiet moments, for instance while Rubuntja waited for his washes to dry before painting on top of them, staff showed the participants recent work by the two artists.

During quiet moments, for instance while Rubuntja waited for his washes to dry before painting on top of them, staff showed the participants recent work by the two artists.

They could hardly stand in greater contrast: Rubuntja with his bold clean palette and strongly graphic style, using dark outlines; Coulthard using a warm but more muted palette, with an emphasis on drawing and narrative elements, including animals that bring the paintings “alive”.

Both artists paint the landscapes of their traditional homelands: for Rubuntja, that’s Tjoritja country, west of Alice Springs; for Coulthard it’s Tempe Downs and the Petermann Ranges to the south-west, although she went to school in Hermannsburg.

Both lament the state of their countries (the result of the introduced plants and animals since colonisation as well as the warming climate): “All our plants died off, all our bush tuckers and things,” said Coulthard. “Buffel grass everywhere now … last year Elders were talking, we will have no traditional food. There’s not much wildlife,” said Rubuntja.

These difficult subjects have been tackled by the Iltja Ntjarra artists in previous projects; for the masterclass though they were doing what has established their renown, painting the country of tradition, the country known to their forebears, their “legacy”, as Coulthard put it.

The participants seemed to have thoroughly appreciated this time ‘in the studio’, perhaps none more so than Mervyn Street in the Mankaja studio at Fitzroy Crossing: “Good to meet you all … thank you, mob … I always have country in my heart.”

The participants seemed to have thoroughly appreciated this time ‘in the studio’, perhaps none more so than Mervyn Street in the Mankaja studio at Fitzroy Crossing: “Good to meet you all … thank you, mob … I always have country in my heart.”

In the Many Hands studio, Coulthard and Rubuntja were tickled. This crossing of paths with other artists and with audiences is one of the attractions of the art fairs and awards events; a Zoom meeting is not the same but it has its undoubted payoffs.

Many of the big name Iltja Ntjarra artists will get their turn at leading online masterclasses in the studio’s own program going through to December. Each one has a theme – such as “The story of Yeperenye (Caterpillar) Dreaming”, “Life in Mparntwe (Alice Springs)” or “Tree Study” – and an inspiration image, sometimes a photograph, sometimes a painting.

The idea is to offer their followers an interesting experience, making up for the restrictions on travel affecting the art centre as well as their potential visitors, whether to the studio in Alice or to interstate exhibitions and events.The opportunity may also bring new audiences to their art.

Until circumstances change it’s matter of making the most of what technology allows, says manager Iris Bendor. And for the time being, at least, the results are pleasing. To their surprise, their virtual stall at DAAF sold 85% of its stock.

Until circumstances change it’s matter of making the most of what technology allows, says manager Iris Bendor. And for the time being, at least, the results are pleasing. To their surprise, their virtual stall at DAAF sold 85% of its stock.

Next test will be at this year’s Desert Mob, always a highpoint in the central Australian arts calendar. There will be a ‘real life’ exhibition at Araluen (slightly pared down, with carefully managed numbers of the galleries and simultaneously online) but the other elements of the event, the symposium and the marketplace, will be virtual.

The artists, local fans and other visitors who make the trip to town will no doubt miss the buzz, but the “global reach” of virtual experiences will be the upside.

Image at top: a ‘skirt panel’ on paper by Selma Coulthard, part of an installation that several of the artists have been working on.