The sound of stockwhips cracking and the thunder of hooves

19 May 2020

This is an extract from An Alice Girl by Tanya Heaslip, published by Allen & Unwin (RRP: $32.99), available 19 May.

This is an extract from An Alice Girl by Tanya Heaslip, published by Allen & Unwin (RRP: $32.99), available 19 May.

Hot on the heels of her first memoir, Alice to Prague– only published in May last year – Tanya Heaslip has launched her second. An Alice Girl explores her childhood growing up on Bond Springs cattle station during the 1960s and 70s.

It was the world that shaped who Tanya is today and the landscape that ultimately drew her back to Australia after the adventure and romance she chronicled in Alice to Prague.

When she was a girl on Bond Springs a trip into town was a big deal and undertaken infrequently. She and her sister and brothers learned everything from their parents, Jan and Grant, and from the land around them, the books they read and through School of the Air.

They had to occupy themselves, with friends of their age visiting only during the school holidays. In this extract – from the prologue, ‘The Cattle Duffers’ – we get a glimpse of one of the ways they did that.

‘Cooeeeee!’

The call ripped through the hot, still air. I swivelled in the saddle, hands tight on the reins, straining to catch the direction of the sound. My skewbald mare Sandy moved restlessly under me, her ears pricked, sensing my anxiety. To the west lay a rocky rise, shrouded by blue-grey mulga, but if the sound had come from behind the rise it was impossible to tell. Behind me a dry creek bed dropped away to the south, lined by river gums wilting in the afternoon heat. There was no sign of anyone there. Nor did it seem a likely hide-out.

I cupped my hands around my mouth and shouted in return, ‘Cooeeeee!’ The words hit the low hills and reverberated back, while above a hawk rose high into the vastness on the currents of a willy-willy. Like my shout, the hawk was soon a speck in the emptiness, swallowed by the big, blue bowl of sky above. Sweat ran down the back of my thin cotton shirt. The sun burned my arms. Time was running out.

‘Cooeeeee!’ I tried again desperately.

Then I heard it, in bursts, through the thicket in the direction of the southern fence. ‘Tanya—over—here!’ I then realised it was M’Lis’s voice, followed by the sound of stockwhips cracking and the thunder of hooves beating through the bush. Perhaps the cattle were breaking away to the rocky outcrop, which would give them cover until they reached that fence. I looked over to what lay between here and the fence. Long, low, flat mounds of red earth sweeping towards the glint of wire in the distance, potted throughout with rabbit holes, treacherous for horses. One misstep and they could break a leg.

My sister was calling for help and that route was the best way to head off the mob. But I couldn’t risk Sandy going down a rabbit hole. So, I took a deep breath and leaned low over Sandy’s neck. We came up straight and fast along a cattle pad, a narrow, dusty track created by cattle meandering to waterholes over the years. It ran across the side of the hill, which was a slightly longer way. Soon my ears were filled with the sound of Sandy’s hooves and my pounding heart. I kept swivelling.

‘Here!’ M’Lis’s voice came to me through the scrub. Then I glimpsed her crouched over a grey horse, hat flattened on her head, flying in pursuit of the fleeing cattle. Behind her came her friend Jacquie, standing high in the stirrups of her horse, UFO, her blonde ponytail swinging wildly.

‘Here!’ M’Lis’s voice came to me through the scrub. Then I glimpsed her crouched over a grey horse, hat flattened on her head, flying in pursuit of the fleeing cattle. Behind her came her friend Jacquie, standing high in the stirrups of her horse, UFO, her blonde ponytail swinging wildly.

Right: M’Lis and Tanya entertaining family and friends around a campfire.

‘Where are the others?’ I called frantically.

They should be nearby. We were a team with a job to do. I just hoped they were covering the flank on the other side of the hill, stopping the cattle being driven down there. But I couldn’t see anyone in this hilly, scrubby corner. Out there, unseen, was my little brother Benny on his grey pony, Lesley, and our friend Donald on his bay gelding.

In the distance I knew my brother Brett, and Jacquie’s brother Matthew, would be heading our way. He’d have my friend Janie with him, as well as another great horse rider, Joanne.

But now everyone seemed lost in the blur and brushlands.

‘They’ve got them!’ M’Lis’s voice came out in frantic bursts through the thick trees. ‘They’re getting away! You take the fence side . . . we’ll cut them off before they reach the creek.’

Our one, desperate job today was to stop the cattle duffers.

Sandy and I cut towards the south, then plunged down towards the length of Kangaroo Flat, focused only on turning the mob. They had a lead on us and I knew we were struggling to make up the gap. If we could stop them reaching the creek, we’d be in with a chance. Where were Benny and Donald?

We knew that the cattle duffers had stolen Dad’s cleanskins— young cattle that had not yet been branded—and were now driving them hard towards their own bush hide-out. And the duffers knew the best secret gorges or wild scrublands to push the cattle into. We knew what they’d do if we didn’t stop them.

We knew that the cattle duffers had stolen Dad’s cleanskins— young cattle that had not yet been branded—and were now driving them hard towards their own bush hide-out. And the duffers knew the best secret gorges or wild scrublands to push the cattle into. We knew what they’d do if we didn’t stop them.

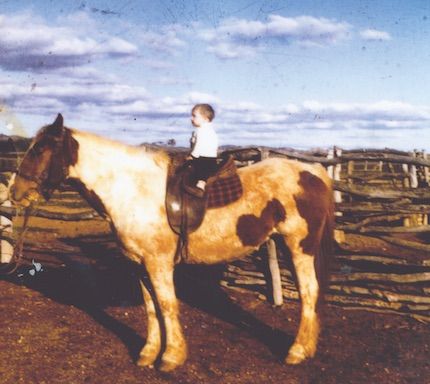

Right: Brett in the saddle, aged 18 months.

They’d build makeshift yards to trap the stolen cattle. Next they’d brand the cleanskins with their own illegal brand and sell them on. And for all we knew, they had some of Dad’s best branded steers, and were intending to cross-brand them too. While the steers wouldn’t be as easy to sell, cattle duffers were cunning and clever and usually found a way to persuade the right kind of people to buy.

We couldn’t let that happen. We were here to protect Dad’s cattle—all of them—at any cost. There was no time to waste.

Then, as one, M’Lis, Jacquie and I were both out onto the open flat—past the rabbit holes, racing across the gibber stones, nothing in our minds now but the safety of the mob, and the protection of the herd. It was now or never to get the cattle out of the clutches of the duffers and herd them back to safety. Our destination still seemed far away. A long, low washout stretching north to south on the eastern end of the paddock, across the dry creek, and then a scramble up the flinty hill that squatted in the middle of the paddock. It was a wondrous hill, we thought, and many years ago M’Lis, Brett and I had named it House Hill.

House Hill boasted a 360-degree view of our world, including the homestead that sprawled away in the distance to the north. On the very top of the hill sat a solitary prickly orange tree. It had defied the droughts and the desert winds year after year, its bark rough and sturdy and its incongruously green leaves pointing defiantly to the high blue sky. We were so proud of the orange tree. So proud that, many years before, we’d crowned it Home Base. That meant freedom and safety for the cattle and us.

To find out what happens next, you know what to do …

Right: Tanya Heaslip. She launched her memoir online from Red Kangaroo Books last night. All photos supplied.

Right: Tanya Heaslip. She launched her memoir online from Red Kangaroo Books last night. All photos supplied.

Good on you Tanya. I so admire the life on a good cattle station.

The essentials: a good Boss and a good Missus.

Tanya, Brett, M’Lis and Ben were so lucky: Great parents, lots of good fun, music, learning essential disciplines from loving parents and companions.

Station kids can ride buckjumpers, walk cattle across Australia, drive trucks, yet they also derive so much benefit from our wonderful School of the Air, today demonstrating to the world the principles of education in isolation.

It’s a great book and I recommend it to all

A fantastic story, and will be shared on the RFTTE.com facebook group!