Film short on answers for trouble in the streets

18 February 2020

COMMENT by ERWIN CHLANDA

Amidst the frenzy to stop the avalanche of juvenile delinquency, hate posts ricocheting around the social media echo chamber, as law and order is chosen by the CLP for its banner election policy, as shops are closing and long time locals are leaving town, Dujuan Hoosan seems to be the wrong kid in the wrong place at the wrong time.

He confesses to have been right in the midst of the nightly mayhem in the streets of Alice Springs. The movie In My Blood It Runs, in which he is the hero, sets out to provide an explanation for his behaviour.

But when the lights went up after the local premiere on Saturday the nearly 500 people in the auditorium had just three questions for the star, and the six members of the production team on the stage for a Q&A: Is his brother jealous of his stardom? (Yes.) How can the community better understand Aboriginal problems? (See below.) And the one which KIERAN FINNANE is leading her review with.

Are we in the same town as the keyboard warriors and the would-be vigilantes? The people clamouring for a curfew? Baying for more cops? Are we on the same planet? Just three questions about a movie that is seen around the world and and portrays Alice Springs people as barbaric towards Aborigines, especially kids?

Here we have a 10-year-old who gets mostly Es at school, as the film reports, but has developed a world view that makes him want to say to the Prime Minister “stop killing Aborigines” and who wants whites to get out of town.

Is this a documentary? No, it is not. It is propaganda, on the back of this child’s story, for an agenda, some of which may be honourable or at least well intentioned. But it is propaganda.

Is this a documentary? No, it is not. It is propaganda, on the back of this child’s story, for an agenda, some of which may be honourable or at least well intentioned. But it is propaganda.

“In My Blood It Runs is not just a film, we have a multi-year impact campaign that dovetails our film release,” as the film’s website makes it clear.

This campaign includes addressing racism; supporting an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander led education system; making schools culturally safe; a restorative youth justice solutions instead of punitive youth justice; raising the age of criminality from 10 to “14/16 years old”; and so on.

And cash: “Your donation will directly support Children’s Ground to establish a school in Dujuan’s homelands, Mpweringke Anapipe.”

So what’s driving this project?

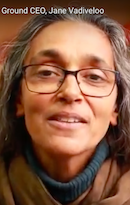

Jane Vadiveloo (at left), one of the leading production team members, the CEO of the Alice Springs NGO Children’s Ground, in town for 20 years “and still learning,” gave an indication during the Q&A which had a lot more As than Qs: “I think we all know the horrendous human rights injustices and abuses that happen every single minute of every single day in every single sector, whether it be prison, education, health. Aboriginal children are 23 times more likely to be in gaol … the constant fear and surveillance that people have to live under.”

Jane Vadiveloo (at left), one of the leading production team members, the CEO of the Alice Springs NGO Children’s Ground, in town for 20 years “and still learning,” gave an indication during the Q&A which had a lot more As than Qs: “I think we all know the horrendous human rights injustices and abuses that happen every single minute of every single day in every single sector, whether it be prison, education, health. Aboriginal children are 23 times more likely to be in gaol … the constant fear and surveillance that people have to live under.”

That is a remarkable statement given that a huge number of people living and working in Alice Springs are focussed on Aboriginal people, responding to their needs, courtesy the taxpayer, of course. Half of the town’s workforce, directly and indirectly, would be a reasonable guess.

Ms Vadiveloo could have added housing, police and youth work to the sectors where Aboriginal needs are massive and disproportionate, and the multi-million dollar budgets of Aboriginal controlled NGOs.

The film’s Leitmotiv is: Alice is a bad place, for Dujuan and kids like him, but all’s good in the homelands (Dujuan has two, Sandy Bore in The Centre, his mother’s, and near Borroloola, his father’s).

The sustained failure to develop employment opportunities on homelands and the costs of servicing are not issues this film spends any time on.

Long-time campaigner William Tilmouth summarised what he took away from the movie. One of the film’s major points is that “Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people love and care for their children” – something being questioned while kids as young as eight are out in the streets, night after night.

Mr Tilmouth says the answers must come from the families: The one which created this film, the many which sustain Aboriginal society with mutual support, but also those who currently are neglectful, failing to provide a safe home for their children who are plunging the town into its current turmoil.

“The leadership in the film came from the family,” he said.

“It never came from the leadership that you see today, from people who live on high wages, have comfortable homes, food in the fridge.

“Those people profess to be leaders, because they head up large organisations, they meet with government people continuously, they have large meetings and sit around drinking copious amounts of coffee, and at the end of the day, nothing comes out of it.

“They ensure the organisation they work for is compliant. No-one asks them to lead.

“In this case here [the film] you could clearly see that the community took ownership and they took control. They handled the solution and they tackled the problem.

“Think about leaders [as people] who will take you to a place where solutions seem impossible, and make them possible. That’s true leadership.

“Think about leaders [as people] who will take you to a place where solutions seem impossible, and make them possible. That’s true leadership.

Mr Tilmouth (file photo).

“Dujuan, his father, his grandfather, they made that solution so easily possible.

“When you see the amounts of money that is thrown at these non-existent solutions … how much would it have cost to bring in police in camouflage?

“No-one wants to listen. It’s a dent in their ego. Get back into your box and be the bureaucrat you were designed to be, because you are definitely not a leader.

“[With this film] the control came from the families, and with a little support, they achieved what every government department, every Aboriginal leader, tries to aspire to.”

Was it just the auditorium lighting or had Mr Tilmouth reddened some faces in the crowd, so short of questions?

It seems that the writer came to this film screening with a set of expectations that inevitably were not met and felt somehow short-changed enough to go as far as accusing the film of being a propaganda stunt.

Is it the duty of the film makers to answer all of the questions troubling this town about law and order or is it enough for it to give a glimpse into the world that many would never see in the hope to broaden understanding and encourage dialogue?

A generous and sensitive undertaking that the family would have made. If the writer did feel so disappointed at the lack of answers, and also lack of questions which he has a dig at the audience about, then why didn’t he ask any questions during the Q and A?

It’s one thing to discredit the authenticity and motives of a film, it’s another thing to report on it in such a way that perpetuates the exact problems that were being highlighted in the film.

Making assumptions about how people in the audience were feeling, making guess work of Aboriginal organisation employment stats are all markers of sloppy journalism boarding on shock jock tactics. This is an opinion piece that does nothing to further the positive work that needs to happen in this town.

In My Blood It Runs is an intelligent look at the issues facing our young people, told, for once, through the eyes of those young people so often ignored or left out of the conversation.

The creative team behind the film prioritise the rights of the family and communities that the doco focuses on. This approach, of putting people at the front of the discussion, is key to change.

The top down, negative, shaming approach predominately taken, and reflected in the attitude expressed by this review, does not work.

It’s a shame that this reviewer did not gain insight from the documentary, however many people will.

In my blood it runs aims to not only educate, but have an actual impact on improving the health and wellbeing of (young) Aboriginal people.

It is only via these methods that the trickle down effect will occur, and alleviate issues most visible (and apparently most concerning) for the community; such as kids on the street at night.

The film reignites the fire to act, and provides actual avenues for change.

@ Kim Hooper: Your response is exactly correct. The film doesn’t provide any form of direction. All it does is pump up Children’s Ground’s square tyres.

@ Kim Hooper: I did not describe the film as a propaganda stunt. I described it as propaganda, not a documentary.

My estimate was of the “number of people living and working in Alice Springs [who] are focussed on Aboriginal people, responding to their needs”. That is not just “Aboriginal organisation employment stats” but includes government instrumentalities.

A significant part of my comment was the verbatim statements by William Tilmouth, a respected Aboriginal leader.

I welcome Ms Hooper’s contribution to the discussion, but I stand by my comment.

Erwin Chlanda, Editor

In a town where the media plays a role in further entrenching the social stratification of its citizens, it is heartening to see a story told from the perspective of Indigenous youth and Indigenous families. This is the role of a documentary: to highlight the voices of the marginalised. Congratulations to the filmmakers, the family and collective behind this production; with intent to increase understandings and create a discourse about the collective struggle Australia faces in reducing social disparities and empowering people to find solutions. A much needed and relevant conversation as evident in the full house attendance of the screening on Saturday night and the response by national media.

Building an impact and outreach strategy around a film (or book or album) does not make that work of art propaganda. Ask Kieran [Finnane] – I’ve provided her with some tips and strategies on this kind of work for her forthcoming book. If she runs with this approach will that make her book propaganda for the peace movement?

What is driving this project and the impact strategy that runs alongside the release of the film are the goals that the family and community on screen have identified.

After the film was completed over 35 people gathered for three days to discuss how they wanted the film to be released and what they hoped it could achieve.

This is because issues of misrepresentation are so common and also because the ethos and process of creating this film ensured that those featured on screen remain in control of the way the film was made and is released.

There is a lot more I would like to share as I feel that this piece misrepresents the film and discounts Dujuan and his family’s experiences.

However, it’s your perspective on the film. Just as this film is Dujuan’s perspective on life and school in Alice Springs.

People can read more background on the project our website.

Alex Kelly

Associate Producer and Impact Producer, In My Blood It Runs.

In My Blood It Runs is on at the Alice cinema from February 27.

Hi Alex Kelly, thank you for your comment.

Kieran Finnane’s second book, as did her first (Trouble), is dealing with facts in a fair and balanced manner which underpins this form of long journalism.

When completed she will promote her book with all elements of the trade as a work of integrity and relevance, and no doubt Kieran will appreciate your advice.

At no time will she accept the suggestion that she is the mouthpiece of one pressure group or another, nor will such a suggestion be appropriate.

By contrast, you describe In My Blood It Runs: “What is driving this project and the impact strategy that runs alongside the release of the film are the goals that the family and community on screen have identified.”

In your own words, the film has an agenda which it serves, which confirms the accuracy of my description as propaganda. It is not a documentary which would have been tied to the requirements of the Journalistic Code of Ethics.

For example, the film communicates to people the world over, by using snippets of the Four Corners program, that in Alice Springs, men in correctional facilities treat children brutally.

At no time does the film report that the events resulted in a $100m Royal Commission, making a string of recommendations, initiating a broad re-think of how to deal with children at risk and children who commit crimes.

I am surprised that none of this was found worth-while to be included in the film, in the interest of balance, by the “over 35 people gathered for three days to discuss how they wanted the film to be released and what they hoped it could achieve”.

You will find ongoing and extensive reporting and commentary about these issues in the Alice Springs News, including our readers’ comment section which of course includes Aboriginal contributors.

Erwin Chlanda, Editor.

@ Alex Kelly: “We all know the horrendous human rights injustices and abuses that happen every single minute of every single day in every single sector, whether it be prison, education, health.”

Hi Alex, just wondering if you can provide any evidence at all to back up [this] quote?

I have just spent two days in Alice Springs hospital and seen the wonderful caring staff in action in the paediatric section. I did not see any human rights abuses or breaches there, to Indigenous or other races.

My wife is a teacher and works closely with year three (mainly Indigenous children), many of whom are in care from the abuse and neglect from their own family, and many have faced incredible trauma.

She has been working closely with children like these for over 20 years and is very well respected by her peers and parents of the children.

Many of these children (now adults) still recognise her and say hello in the street, as do the parents of these children.

Can you explain what injustices and abuses occur at her school?

I work with Aboriginal adults and have done so for 17 years. I too have not seen this abuse and injustice “every single minute, every single day”, in fact I have rarely ever seen it, if at all.

I would hope that you would make a public apology or retraction for these comments unless you have evidence.

If you do have evidence, have you reported it?

One of the other interesting points I see on your website is that “children do not belong in custody”.

I tend to agree with that, however I wonder if your foundation (that must be funded quite well by the government) does not seem to make the connection that if 12 year olds are not on the street at 2am, or breaking into houses, or stealing cars, or smashing property, that they would be far less likely to end up before the courts.

Unfortunately, after many diversions, many “second” chances, many “opportunities” they may be placed in custody, as a last resort.

Could you use some of your funding to educate the parents of these children that a safe home will be of benefit?

So it seems you have insulted our wonderful teachers, health staff and others in a quest to portray your movie the way you want.

From many of the comments, the critical review by Alice Springs News, and some of the professionals who have been to a pre-release screening of your film, it seems like you have once again used race to push a narrative, and cause further division in our community. Well done.

@ Erwin: To be clear, I make a distinction between the film and its content and the project – the campaign and release strategy.

I was speaking specifically to the impact and outreach release strategy when I said: “What is driving this project and the impact strategy that runs alongside the release of the film are the goals that the family and community on screen have identified” and spoke of the 35 people strong planning meeting.

If it was not clear this strategy meeting was for the *release* of the film and the process of addressing the content of the film itself was very different.

We didn’t start with goals and work backwards to create a film that fit them, we started with the story as it unfolded and built the impact strategy around that when the film was completed, which I regard as critical to doing this work well and not producing what you call propaganda.

It’s a two-edged sword. Many years ago when I was a secondary teacher, an Indigenous boy threw a chair across the room, obviously endangering others.

I took him out of the room to point out the error of his ways. His exact response was: “You can’t touch me. I’m Aboriginal”.

On another occasion a girl was badly behaved and interfering with the learning of others.

When I talked to her she claimed that I was picking on her because of her skin colour.

I responded by saying that my own children had the same skin colour as she had (they are part Fijian). The response was yes but they are not Aboriginal.

A friend of ours, a security guard, apprehended a young Indigenous shoplifter and was threatened with legal action if he was touched.

One has to ask where these ideas that these kids have to have special treatment originate?