The stolen child who went to university

8 February 2019

A series about high achievers from Central Australia

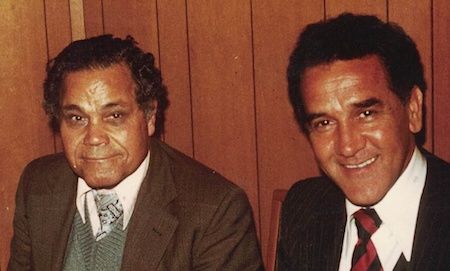

Joe Croft, left, the first Indigenous person to enter an Australian university (University of Queensland in 1944) with Charlie Perkins, right, the first Indigenous person to graduate from an Australian university (University of Sydney, 1966). Taken in Adelaide in 1980.

By JOHN P McD SMITH

Stolen child Joe Croft grew up at The Bungalow in Alice Springs and became the first Indigenous Australian to enter university.

Most of the stories told about the Stolen Generation are understandably sad, but this one is a little different. This is a story of goodness, compassion, forbearance and success with a quantity of sadness in the mixture. This is Joe Croft’s story.

A descendant of the Gurindji and Mudpurra people from the Northern Territory, Joe Croft was forcibly removed from his mother at just three years of age and spent his childhood in government institutions including The Bungalow, the historical Telegraph Station in Alice Springs.

Joe barely remembered his mother when he was taken from her at the age of three on Victoria River Downs Station in the Northern Territory in about 1929.

All he knew was the loss of warmth and comfort and a feeling of inexplicable loneliness as he sat in the back of a dirty, rough government truck on his way to Kahlin Compound in Darwin. Joe’s mother followed her son to Darwin, but Joe didn’t know. Kahlin was overcrowded so Joe was soon on his way south to the Pine Creek Children’s Home and his mother now lost track of him.

However, Joe didn’t stay at Pine Creek long either for he was soon in the back of a truck again on his way south to the Government Compound at Jay Creek west of Alice Springs.

Here he was bundled into an iron shed that served as a dormitory. There were many unhappy and confused children at Jay Creek who had been drawn from the surrounding station and settlements.

Local pioneering school teacher Ida Standley and well know local Aboriginal woman Topsy Smith were very kind to the children and did their best to compensate for the trauma the children were suffering because of the separation from their mothers.

What a travesty it was that the white fathers did not want their children and the Aboriginal mothers were not allowed to keep them.

Joe began to learn to read and write and he grew to love the walks and picnics into the hinterland of the MacDonnell Ranges.

Not too much time went by however before the government trucks rolled into the compound to take the children away yet again.

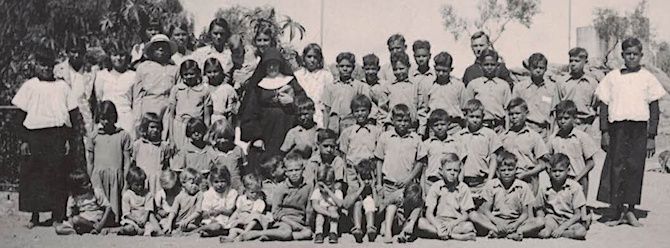

Anglican children at The Bungalow in 1938-39. Joe Croft is the altar boy at the far left. Father Ken Leslie is standing at the back to the right. Sister Kathleen is standing in the middle row.

The vehicles unceremoniously rumbled along the dusty road into Alice Springs where the children were driven to the site of the Old Telegraph Station, two miles north of the town.

At least there was plenty of water from the springs, while the living conditions, though barely acceptable, were an improvement on Jay Creek.

Joe soon found himself an iron bunk in the boys’ dormitory on the lower of the three tiers. Mrs Standley was now gone and Joe did not like the new superintendent. The man was a bully and abusive to the girls and everyone feared him.

It wasn’t all bad for another person came into Joe’s life.

He was the Anglican priest who had some to Alice Springs in November 1933 to begin the first parish. His name was Father Percy Smith. He had been expressly asked by the Bishop of Carpentaria, Stephen Davies, to give special attention to the children of The Bungalow seeing that 80% of them were baptised Anglicans.

Every Wednesday and Sunday Father Smith would come to The Bungalow to minister to the children and Joe became a server.

He and Father Smith were soon good friends. Often Father would have to walk the two miles to the Old Telegraph Station and the children would watch to catch sight of the slight figure coming along the dusty track carrying a small case.

Father Smith soon appreciated Joe’s potential and with assistance from the head teacher, Walter Boehme. They helped Joe to study for his Qualifying Certificate, which he passed admirably.

Father Smith was keen for Joe to go onto secondary education. Native Affairs wanted Joe to go to Adelaide, but Father Smith would not agree because there was nobody there with whom Joe would identify.

Eventually the government allowed Father Smith to arrange for Joe to go to All Souls’ Anglican School, Charters Towers in Queensland. Father Smith’s sought support from his brother, C E Smith, who was a member of the board of governors of the school.

He made the arrangements for Joe’s enrolment. C E Smith and his family became a critical support for Joe after his relocation to Queensland in 1939.

Father Smith was confident that Joe could show Australia what Aboriginal people could achieve given the right set of circumstances. The only money that the school received for Joe’s tuition and board was what came from the NT Native Affairs branch.

Joe did exceptionally well at All Souls, passing both his junior and senior certificates. The headmaster Canon O’Keeffe took special interest in Joe and he graduated in 1943 after becoming school captain, prefect and captain of the cricket, football and swimming teams.

In 1944 Joe was awarded a Commonwealth scholarship to attend the University of Queensland to study engineering and became a resident of St John’s College, making him the first person of Aboriginal descent to enter an Australian University.

His academic results were very good, but with the impact of the second world war he left university to join the army. There is little doubt that if Joe had continued his studies he would have graduated.

After the war he qualified as a surveyor working on dam building and railway line rebuilding projects from 1950 until 1971. He married, had two children and in later years worked for the Department of Aboriginal Affairs in Canberra and also served on the Anti-Discrimination Board.

Joe always acknowledged the role that Father Smith and the Anglican Church played in his formative years, but not withstanding this nothing can detract from his determination, his will to succeed against exceedingly difficult personal odds, his positive and outgoing personality, his humility and his desire to do the best for his own family.

It was indeed a just reward for Joe that in 1974 he was reunited with his mother Bessie after a separation of forty-five years. When they met in Darwin his mother instantly recognised him!

Joe Croft passed from this life on July 22, 1996 aged 70 and his family took his ashes to his tribal home in Kalkaringy, Wattie Creek, NT to be buried in the land of his ancestors.

His daughter, Brenda, writing in 1998, had this to say about the Stolen Generation: “Aboriginal people who were taken away from their communities often travel vast distances in a subliminal, as well as a literal search for themselves and a place to belong. My family was fortunate that so many people kept their memories and gifted them to us, helping fill in the missing pieces.”

During the 1990s All Souls School recognised the achievements of its former student, the late Joe Croft, with the establishment the Joe Croft Scholarship. It assists suitably qualified Aboriginal students to attend the school.

The school also named a stand at the O’Keefe Oval, the Joe Croft Pavilion and in 2015 the University of Queensland created the Joseph (Joe) Croft Indigenous Award in his honour.

[The author, John P McD Smith, is the son of Father Percy Smith (1903-82), first resident Anglican priest in Alice Springs in 1933. John has written his father’s biography, The Flower in the Desert.]

I trust all racist ignorant followers of the Promised Land acknowledge the clear fact that there was never a “stolen generation” and that the vast majority of similar “needy” children today would benefit likewise if they were in fact “stolen” today.

I hear where Peter is coming from there. I fear the Government is far too concerned with being labeled something (by people who want to remain ignorant of what is going on) instead of doing what is right for children.

While I appreciate it is important to never let go of the culture and keep it strong, how do you think kids are going to do that are brought up by absent or alcoholic parents, in an environment where they might be raped or married off at an extremely young age, their families don’t see the importance of school by making them attend every day and they have no safe home to go to at night.

It is very obvious this isn’t the case for a very large portion of Aboriginal kids but for the few that this is a daily life struggle, they need help, and now.

Saying they need to remain with family to keep their culture is just saying turn the other cheek and allow all of the above to happen. Imagine these were you kids.

Thanks John, for your sensitive tribute to a deserving man.

Not stolen. Rescued, nurtured, protected, educated, empowered, but not stolen.

True Peter, sadly what happened when many of these children were taken away was traumatic, however the biggest mistake was the acceptance of the misnomer, stolen.

True, the term stolen usually means taken without permission, but unfortunately this term fails to address the reason they were taken.

In almost all cases it was due to either neglect or an inability to provide a safe environment, and in context, based on what European standards at the time deemed a safe environment.

There have been many prominent Aboriginal people who have gone on record claiming they were stolen, but this often led to heartbreak when the real circumstances are discovered, that their parents were unable to provide for them, for various reasons.

It’s easier to say the government stole you rather than say your parents were unable to provide for you. There has only ever been one truly stolen person in any court case in Australia.

Bruce Trevorow, who was adopter out when his parents left him in hospital and were uncountable for over 12 months.

The term stolen generation is now morphing into the more emotive term genocide.

In the meantime the children continue to suffer.

Local1 – you summed it up perfectly. No-one wants to admit, learn or accept that their parents were unable or unwilling to provide care for them.

So it’s much easier (and preferable) for them to “believe” they were stolen. And now we have $ attached which increases the number of people and empire-building organisations wanting to perpetuate the stolen myth – but the issues around the current generation of neglected kids is a subject that many still choose to ignore.

Hiding behind the smokescreen of culture just gives people an easy way of avoiding honest discussion (and practical actions) to address the shocking reality.

Two amazing men that were successful in their lives. Positivity at it’s best. Their families have also become successful in their own right. Congrats to the families.

I understand that the term Stolen Generation was first penned by Sur Ronald Wilson, president of the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission in his HREOC report. In 1996.

All discussion should begin with that report and Sir Ronald’s use of the expression.

I do not know if it was Sir Ronald’s inspiration or whether someone else coined it and he simply appropriated it.

Whatever the origin, it is now a fundamental part of the children-at-risk community dialogue.

We need to get some things straight here.

If policemen, holy men of the cloth, miners, pastoralist, vagabonds of the day, had kept their trousers buttoned up and not pursued Aboriginal women, there would not be a stolen generation, that is, children sired by non Aboriginal men as those described.

And those kids were stolen from their mothers.

What does taken by force from their mothers not to be seen again mean then?

Like many other Aboriginal mothers whose kids were stolen, Joe Croft’s mother tried to find him looking all over for him as described in this story.

Was that an indication of an uncaring mother? I don’t think so.

Many mothers only found their stolen kids 40 to 50 years later if they were lucky and not died before they could.

They were stolen by the government of the day out of embarrassment it brought on white society, not out of care for those kids’ well being.

There was no alcoholism or such problems in those days amongst Aboriginal people to be a cause to snatch those kids.

All those are today’s issues, unlike those days. A different case and concern altogether.

Thanks for sharing this amazing story, John. I never knew about Joe Croft. It is incredible what he was doing as early as the 1940s.

Worked with Joe Croft in DAA in Canberra.

Crofty was a goodhearted bloke and he listened to what everyone had to to say.

That struck me about Crofty. He was a great listener.

Great historic photos. Some of the people in the group photo look familiar. That may be a very young Charlie Perkins sitting in front of the Sister, with his head turned to his left.

@ David, Posted February 11, 2019 at 11:00 pm: “We need to get some things straight here.

If policemen, holy men of the cloth, miners, pastoralist, vagabonds of the day, had kept their trousers buttoned up and not pursued Aboriginal women, there would not be a stolen generation, that is, children sired by non Aboriginal men as those described.”

Your comment underlines the fact that those children were part of two communities: Aboriginal and European.

I am in total agreement with you, it was a disgrace that those children were stolen from their mother; but in this period of history women of any skin colour did not have many rights.

Amazing to see the Perkins legacy continue with Rachel Perkins, centre stage, at the launch of the YES campaign this week. The Smith, Perkins and Croft families should be proud of this. This is what bringing black and white together should be all about – sharing these stories. Not celebrities saying vote one way or another.