Centre art stands out in SA festival

8 December 2017

By KIERAN FINNANE

Like familiar faces in a crowd, the works of Central Australian artists jump out as I visit Tarnanthi, billed as a Festival of Contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art at the Art Gallery of South Australia in Adelaide.

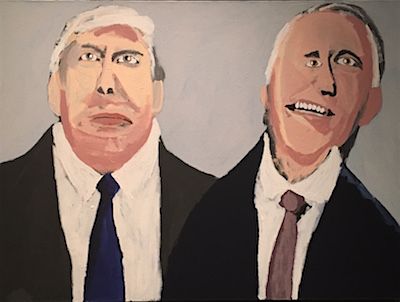

And they are faces, many of them. Portraits by Vincent Namatjira – sorely missed at the 2017 Desert Mob, which he opened – are there. ‘The Donald’ has caught his attention, although in both instances it is the man alongside who is captured more perceptively, Barack Obama and Malcolm Turnbull. His Turnbull (right) reveals the unease behind the Prime Minister’s trademark bland smile.

And they are faces, many of them. Portraits by Vincent Namatjira – sorely missed at the 2017 Desert Mob, which he opened – are there. ‘The Donald’ has caught his attention, although in both instances it is the man alongside who is captured more perceptively, Barack Obama and Malcolm Turnbull. His Turnbull (right) reveals the unease behind the Prime Minister’s trademark bland smile.

And Namatjira’s intriguing self-portrait alongside billionaire Gina Rinehart underscores how wide-ranging he is in his scrutiny of the outside world from his base in Iwantja Arts in South Australia’s far north-west. His interest was apparently sparked by her appearance in the list of Australia’s richest in Forbes magazine.

“I’m interested in who these people are and how they made their fortunes,” he is quoted as saying in Adelaide Now (April 26, 2017).

“Their lives must be really different to ours – from mine and my friends and family’s.”

Perhaps the rich and famous think similarly when they are afforded a glimpse into the Aboriginal world, such as that offered by the series of faces from Yarrenyty Altere Artists. As inventive as ever, nine artists have richly embroidered faces (left, detail), each with its own distinctive character, and mounted them on tall sticks. This suggested to me spirit figures although the collective title of the work seems more human-centred: Every face has a story, every story has a face: Kulila!

Perhaps the rich and famous think similarly when they are afforded a glimpse into the Aboriginal world, such as that offered by the series of faces from Yarrenyty Altere Artists. As inventive as ever, nine artists have richly embroidered faces (left, detail), each with its own distinctive character, and mounted them on tall sticks. This suggested to me spirit figures although the collective title of the work seems more human-centred: Every face has a story, every story has a face: Kulila!

This last word means ‘listen’ and has been taken to heart by Tarnanthi’s artistic director, Nici Cumpston. The exhibition is notable for its presentation of multiple Aboriginal voices, whether through audio-visual supporting material or in interpretive panels, explaining the background to the work and offering insights, often poetically expressed.

Scale and ambition continue to mark the work from artists in the APY Lands. A huge, amazingly coherent canvas telling the story of Kungkarangkalpa: Seven Sisters (below) is the work of 24 women artists, “as old as 90 and as young as 17”, in the words of one of them, Nyurpaya Kaika Burton.

“This is a story about strong women,” she says. “It is about women looking after each other and working together to stay safe.”

For the men from the Lands, 23 of them, their monumental canvas, Kulata Tjuta, is in tribute to the late G. Ingkatji, a painter, ceramist, cultural leader and teacher.

‘Kulata’ means spears, which have been a dominant motif for many of these artists in recent years. Movingly, a collection of spears and spear-throwers, miru, are laid out in front of the painting, the miru inscribed with the names of a number of senior men who have passed away. They include G. Ingkatji himself and another wonderful artist and leader as well as curator, H. Tjupuru Burton who died in February this year.

Paying tribute is also the impulse behind a major installation (left) from men and women of the Lands (I counted 59 names). It too is titled Kulata Tjuta and is dedicated to the late Y. Lester and his long-standing fight “for recognition of Maralinga and Emu Field.”

Paying tribute is also the impulse behind a major installation (left) from men and women of the Lands (I counted 59 names). It too is titled Kulata Tjuta and is dedicated to the late Y. Lester and his long-standing fight “for recognition of Maralinga and Emu Field.”

The work brilliantly uses kulata to evoke the atomic explosions at Maralinga and Emu Field that took Mr Lester’s eyesight, dispersed his people, and caused injury and death to an unknown number of them. This has never been properly recognised or compensated. Beneath the kulata are the carved piti which no doubt stand for people and country as one.

Coming in Mr Lester’s footsteps in focussing attention on the Maralinga legacy in recent years has been Mumu Mike Williams, and works by him in collaboration with Sammy Dodd are in the room leading into the Kulata Tjuta installation. The atomic tests are not explicit in this work but it continues in the vein of his appropriation of maps and mail bags (as with the worked acquired by Araluen out of Desert Mob this year) to assert Aboriginal presence and rights in their land. In the same room is a multi-panelled video installation that tells the compelling Maralinga story.

In a year when so much has happened for the Namatjira family, including the restoration of Albert Namatjira’s copyright to his descendants through a trust, Tarnanthi adds to the interest: in terms of Aboriginal art history and Namatjira’s place within it; and in terms of the contemporary revitalisation of the and Hermannsburg watercolour school.

On the lower ground floor, artists of the Iltja Ntjarra Many Hands Art Centre have responded to historic photographs by Rex Battarbee and possibly Albert Namatjira of places the pair listed and painted.

On the lower ground floor, artists of the Iltja Ntjarra Many Hands Art Centre have responded to historic photographs by Rex Battarbee and possibly Albert Namatjira of places the pair listed and painted.

Right: Photographs of men with donkeys, attributed to Rex Battarbee and Albert Namatjira, and the response works, top, by Gloria Pannka and bottom, by Reinhold Inkamala, who has introduced the Hermannsburg Mission into his composition.

The contributions to this series of younger artists alongside their established elders speak to the renewed drive of this art centre and of attention to this work. I was particularly struck by the work of Reinhold Inkamala for his observations, his free adaptation (which was actually common to many of the artists’s responses) and for his painterly style.

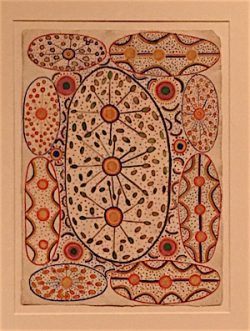

On the first floor of the gallery it is fascinating to see two works in watercolour and pencil on paper, attributed to Albert Namatjira, depicting traditional motifs related to the bush onion (yalke) totem place in Nuamana, Palm Valley (below left). Alongside this work are examples of the more familiar watercolour landscapes of Albert and his sons as well as some superb early works from Papunya. These include two by the illustrious Kaapa Tjampitjinpa, both from 1971.

In the current Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory exhibition devoted to the early Papunya works, Tjungunutja, there are only three on show by Kaapa, with others by him restricted from public viewing. So it is a treat to see these and to see visually expressed in the display the deep links between Namatjira and the Papunya painters.

In the current Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory exhibition devoted to the early Papunya works, Tjungunutja, there are only three on show by Kaapa, with others by him restricted from public viewing. So it is a treat to see these and to see visually expressed in the display the deep links between Namatjira and the Papunya painters.

Elsewhere on this level, some displays draw out the broader Australian art context in which Aboriginal art has been produced and received and on which it has had an influence. A marvellous watercolour landscape by Otto Pareroultja thus hangs in a modernist decor (see below). On the floor is a 1960s hand-pulled woollen rug by an unknown maker from Ernabella, but other pieces in the display are by non-Aboriginal artists and designers.

The curtain fabric for instance was designed by Frances Burke in 1965, using a bold pattern of shields. It is interesting to think about how unlikely this would have been in decades earlier and again now and why this is so, what it says about the Australian “you, me, them, us” that is the focus of the displays in this room.

This focus on work from Central Australia is a personal one. There is much else to see in this wide-reaching exhibition, including, for me, a memorable installation by Yolngu artist Ishmael Marika, incorporating enthralling archival film of his ancestors dancing a sunset clouds songline, and selections of paintings by Western Australian artists Nyaparu William Gardiner (Nyangumarta/Warnman/Manjilyjarra people) about experiences in mines and on stations in the Pilbara, and Ngarralja Tommy May (Wangkajunga, Walmajarri people) whose work about his country is rendered with exquisitely fine brushing.

Tarnanthi was staged at multiple venues in the city in October; the exhibition in the Art Gallery of South Australia opened then and goes until 28 January 2018.