Rock climb to close: Who wins?

3 November 2017

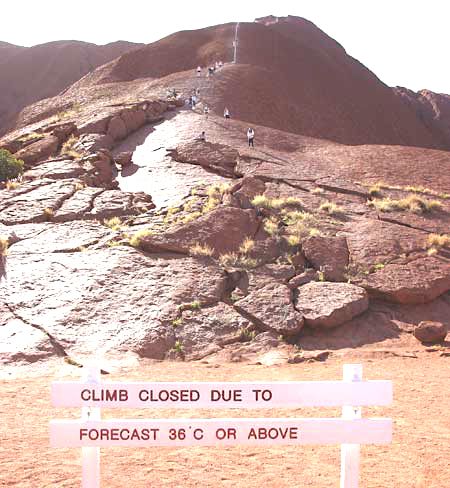

ABOVE: “Joint management” can have surprises store in store for our major tourism assets. Are the West MacDonnells next? Check about the highest peak of Mt Sonder being off limits. BELOW: Climbers ignore the sign at the base of The Rock.

COMMENT by ERWIN CHLANDA

COMMENT by ERWIN CHLANDA

There is no question that climbing Uluru is one of the most superb tourism experiences in Australia. It will come to an end in two years’ time – officially, at least.

Restrictions in which other parks are next?

Parks run both by Parks Australia (Canberra) and Territory Parks (Darwin) have management structures that gives decision making power to a handful of private owners while the general taxpayer foots the massive costs.

For example, in 2016/17 the Uluru management board of 12 had eight Indigenous members. On the board of the West MacDonnell Ranges, vital for the development of the tourism industry in Alice Springs, the numbers are 13 Indigenous, two non-Indigenous.

In my 41 years in The Centre I’ve climbed The Rock perhaps seven times, and been in that national park probably 300 times.

A mate and I climbed it on a stormy night that was so black that we had trouble seeing from one white mark on the ground to the next. We were climbing mostly on our hands and knees. The already fierce wind, accelerated by the half-venturi effect at the top, threatened to blow us into the void.

This is a world away from today’s regimented and constrained tourism.

My other climbs over the years were benign and the view over the desert and across to the Olgas (as they were known then) was magnificent beyond description.

Over the years I encountered vastly different opinions about climbing The Rock.

To me the most significant came from the most senior of all custodians, the late Paddy Uluru, decades ago. I was talking with him alongside the monolith.

He said, words to the effect: If you are stupid enough to climb it, go for it. He surely wouldn’t. He said there is not much water up there, if any; hardly any plants and no game.

But he would never tell me the full story about The Rock, he said, only a few basic parts of it. It’s the story that is sacred and secret, not the landform.

Clearly there are other views abroad today as this week’s statement by Sammy Wilson illustrates.

Sustained opposition to climbing over the years has come from predictable sources and the debate, usually heated, has been chronicled in tens of thousands of words in our seven million word archive on this site (google it – and don’t forget to use the name Ayers Rock as well).

The official version of the climb decision, dutifully trotted out by the majority of media yet again, displays a surprising and deplorable attitude toward sacred sites.

In most other countries they represent the essence and beauty of religious faiths whose adherents would say to you, come and see our sacred site, enjoy it, learn from it, feel elevated by it. It would be needless to say respect it.

It would be absurd to expect the Catholics to discourage anyone from visiting the Papal Basilica of St. Peter in the Vatican and exploring every nook and cranny. They wouldn’t dream of telling tourists to just look at it from a distance.

So who are some of the usual suspects against climbing, and what are they on about?

• Aboriginal activists were having a ball for decades threatening closure: For every “gun to the head” of traditional owners there was one to the head of the tourist industry or government.

• Rangers and tour guides: It’s a big task to carry down people who’ve had a heart attack. However, full marks to those who are and have been providing the safety backup for an iconic adventure for millions of people. A reported 35 have died since climbing started to become popular in the mid 1930s.

• Those who foist views against climbing, which they are entitled to hold for themselves, onto others who regard climbing as the adventure of a lifetime. As it turns out the the nay sayers are now getting their way.

• Those who argue that only 20% of visitors now ascending the climb, and therefore closing it is OK. That’s a cynical Furphy: The decline is largely caused by temporary closures imposed by the people who have the most to gain from it – park staff. They often draw a long bow on safety issues, or at times cite reasons with no links to safety.

• The numbers are perhaps also down because people who want to climb have given up, recognising the chances of being allowed to climb are slim. They just don’t go to the Uluru park. The climb was closed for parts 229 days of the 273 days between January 1 and September 30 this year. That’s 84% of the days.

Both NT and Federal parks have management boards that have the power to instruct the lessee, namely the respective government parks services. These services are obliged to follow board instructions.

“They’re both boards of joint management, not advisory bodies,” says the Central Land Council.

In the case of Uluru the board must have an Anangu majority. In fact in 2016 it had eight “traditional owner nominees” chosen by the Federal Minister from nominations by the Anangu community, according to the Parks Australia website.

The other four board members were Sally Barnes, Director of National Parks, two people nominated by the Ministers for Tourism and Environment, respectively, and one from the NT Government.

So we have a tiny group of people in control of one of the nation’s most significant tourism assets, owned outright by a small number of private people, and operated by a staff entirely paid for by the taxpayer. Good work if you can get it.

The 2016 annual financial report of Parks Australia, whose parks apart from Uluru–Kata Tjuta also include Kakadu and Booderee, lists “receipts from government” as $40.5m.

There are 32 national parks under joint management with the NT Government, including the West MacDonnells, Finke Gorge, Watarrka (King’s Canyon), Trephina Gorge, N’Dhala Gorge, Emily and Jessie Gaps, Arltunga, Chambers Pillar, Ewaninga Rock Carvings, Rainbow Valley, Alice Springs Telegraph Station and Ruby Gap.

Their joint management structure is similar to the one at The Rock.

Says Chris Day, director of Central Australia Parks in theDepartment of Tourism and Culture: “The Tjoritja / West MacDonnell National Park is a Joint Managed Park.

“The land owners are the traditional owners for those lands held by the Tyurretye Aboriginal Land Trust and the park was leased to the NT Government for 99 years.

“It has a joint management committee that represents the partners – traditional owners and government.

“The committee is the governing body of the park which approves local guidelines and criteria to guide decision making, strategic plans and some permits including commercial operations,” Mr Day says.

“The committee is the governing body of the park which approves local guidelines and criteria to guide decision making, strategic plans and some permits including commercial operations,” Mr Day says.

“The committee has 15 members, 13 of whom are traditional owners, and two park / government representatives. This number is not defined by legislation so it could be varied.

“The committee members are nominated and accepted by the traditional owner family group, who are members of the land trust holding title to the land.”

Parks and traditional owners’ interests have clashed before, and recently this little gate (above) has appeared just off the Larapinta Trail.

Heading off on the trail towards Alice Springs from Standley Chasm, you first climb “the Staircase to Heaven”, leading to an outlook with a 360 degree view that will take your breath away.

Trekking down the other side you come to a creek that flows towards the chasm and through it. To continue the Larapinta trail you turn left – upstream. But if you turn right – downstream – a wonderful walk, mostly in the shade between two ranges, will take you to the northern end of the chasm.

It’s a two or three hours round walk for reasonably experienced walkers back to the charming and increasingly popular restaurant and camping ground. But what’s with the gate?

RELATED READING:

(Links takes you to the issue in our foundation archive, scroll down to find the headline)

Mt Sonder fiasco dims hopes for parks strategy.

Mt Sonder ban “lifted”.

What happens when the Basilica is being used for a religious ceremony?

Maybe the gate is part of the 40.5m from the government and cost them $100,000 to put in and another 25,000 for the lock?

Reduce the entry fee to $10 or potential tourism will die.

Peter Dixon: I assume you mean St Peter’s in Rome?

If so then I can tell you that nothing happens to the tourist flow when a relgious ceremony is in progress, even when that ceremony is conducted by the Pope.

I learnt this when I was lucky enough to be invited to a beatification ceremony at St Peters a couple of decades ago.

It was an amazing experience not least because neither the participants in the beatification ceremony or the crowds of talking tourists allowed the other party to interfere in their activities.

Interestingly, though the tourist babble offended my idea of the sacred it did not disturb my Italian sister-in-law’s sense of what was sacred at all.

She found nothing offensive in the tourists behaviour.

Like most of her religios peers, my sister-in-law locates the spiritual in the content of the service not the ambience of the surrounds.

What this suggests is that our ideas of the sacred are cultural creations and hence things that are always open to negotiation rather than non-negotiable absolutes.

Whilst it seems there is little doubt that many Anangu worry for those who climb The Rock, and that there are many sacred sites located on it, I don’t think that Paddy Uluru or the other Aboriginal men who took tourists up the rock in the 1930s held the same notion of sacred as your argument implies.

My own reading of the historical archive has lead me to believe that these men, of whom Paddy Uluru was probably the most famous, had a much more “Italian” (to continue the metaphor) notion of the sacred.

That is to say, like my sister-in-law, Paddy did not regard people climbing the rock as incompatible with its sacristy.

From this it follows that the debate about whether to climb or not to climb The Rock is both constructed by and helping construct what we (Australians) mean by the term sacred.

That, as the analogy with the Basilica suggests, we are increasingly defining the sacred as the antithesis of the secular (also evident in the increased sacrilisation of ANZAC Day) bothers me.

Though the constant chat which happens when I go to church in Italy with my sister-in-law still ruffles my Anglo-Australian feathers, I have come to respect that it does not diminish her faith.

All of which is to say that how we honour the sacred comes in many different forms.

I would hate us to lose our sense of the cultural diversity of sacristy in the debate about whether we should or should not climb The Rock.

@ Megg Kelham (Posted November 4, 2017 at 8:28 am): Thank you for your constructive and informative comment.

I’m aware of examples from the past that demonstrate Aboriginal people did not consider climbing Uluru to be offensive, indeed they quite readily did so themselves.

The notion now apparently prevailing that Anangu consider Uluru to be wholly sacred and that no-one should climb it is a confected belief of very recent origin but inevitably parroted by an uncritical mainstream media that’s too lazy or timid to investigate the truth.

Personally I’m not fussed about the closure of the climb on Uluru but it will be interesting to see what consequences, if any, eventuate over time.

A trite argument regularly trotted out by those insisting on the closure of the climb at Uluru is to compare its sacredness to that of St Peter’s basilica in Rome. Megg’s post provides a neat refutation of this simplistic nonsense.

I have my own experience as a tourist visiting St Peter’s – not in Rome but in Riga, the capital city of Latvia. St Peter’s Church with its spire is the tallest cathedral or church in Riga’s Old City; and within that spire is an elevator which takes visitors to two viewing platforms at the top.

St Peter’s church spire is a major visitor attraction, providing great views over the Old City and nearby Daugava River.

It was literally the very first attraction I visited, taken there by my friend who is a Latvian native and not at all affected by the “sacredness” of taking a ride up a lift in a church spire to view the panorama of the city.

Cut the funding and maybe the self proclaimed “custodians of country” might find themselves between the rock and a hard place.

@ Megg Kelham: “Your argument”? Whose? I wasn’t making any argument – just asking for information which you have given, thank you.

No land belongs to anyone on this planet, that’s the fact you shouldn’t deny!

The land belongs to mother nature! We just occupy it and try to make money out of it.

Ayers Rock (Uluru) is a good example of it. Nowadays custodians occupied that land in the 50s and drove away the original owners or better said occupants.

So, why should that tourist attrcation be restricted?! It’s too much ado and blah blah blah for nothing.

Lived in the centre for many many years, carting tourists to The Rock, but preferred to show them the real and other spots of the centre.

Too many lies at Uluru, and blame and shame on parks management and so-called custodians etc. After so many years in the centre I simply gave up, had enough and fled, by good reasons!

Is this writing eye-opening? Maybe, maybe not, depends who you are, either a pro-Aboriginal-activist with no real knowledge about their culture, or a well-educated normal living being!

Cheers and enjoy the better places of the centre!