Walking, writing between frontier and home

17 August 2017

Archived article

REVIEW by KIERAN FINNANE

REVIEW by KIERAN FINNANE

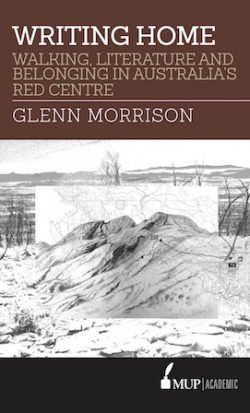

Writing Home: Walking, Literature and Belonging in Australia’s Red Centre

By Glenn Morrison

Melbourne University Press, 2017

326 pp.

Songlines and Fault Lines: Epic walks of the Red Centre

By Glenn Morrison

Melbourne University Press, 2017

188 pp.

It is not often that two books from the one author appear in such quick succession. In mid-March Alice Springs journalist Glenn Morrison launched his Writing Home, the publication of his literary doctoral thesis; five months later comes Songlines and Fault Lines, essentially the same work rewritten for the general reader or as Morrison (pictured at its launch in the Red Kangaroo bookshop) puts it, “with the dead French theorists taken out”.

I was keen to read both, for the interest of Morrison’s subject matter primarily but also to see how he managed to translate a densely referenced book of ideas on “Walking literature and belonging in Australia’s Red Centre”, the subtitle of the first work, into the pitch of the second work, subtitled “Epic walks of the Red Centre”, which sounds more like an offering to the adventure-oriented tourist.

In brief, Morrison does this well, staying with the ideas, breaking down the abstract language, filtering out some of the theory, and adopting a more conversational tone. He also adds his own narratives at the start of each chapter, orienting the reader, in the familiar modes of travel writing and journalism, to the locale of the “epic walks” whose literary construction and meaning he goes on to discuss.

This, however, is not what is most interesting to note in Morrison’s achievement. Rather, it is his challenge in both works to the idea of ‘the frontier’ as a way of conceptualising how we think about Central Australia. For settler Australians it has been the dominant idea from the start, tenaciously so, although along a spectrum of “porosity” that Morrison traces through the various literary accounts he examines.

He asks whether the idea of the frontier – representing the Centre by opposing binaries such as nature / culture, primitive / modern, wilderness / settlement, real / other – gets in the way of settler Australians being able to reimagine The Centre as home, a place of intercultural exchange and emergent hybrid culture.

He asks whether the idea of the frontier – representing the Centre by opposing binaries such as nature / culture, primitive / modern, wilderness / settlement, real / other – gets in the way of settler Australians being able to reimagine The Centre as home, a place of intercultural exchange and emergent hybrid culture.

The literary accounts he selects are “walking narratives”: they all retell a journey on foot. It is not hard to see the value of this criterium, as it is the foundation of the earliest representations of this country, the stories of the Dreaming (the songlines of his second title). “Walking is something we share, Aboriginal and settler. It defines us as humans,” writes Morrison. The encounter through the body with the landscape, he argues, could open up for the walkers, and those who read or listen to their narratives, possibilities of shared ways of being in it.

Left: Cover art for the academic title is by Alice Springs artist Deborah Clarke.

Before such an encounter, its space – the country or landscape – exists; it is constructed as place by the “embodied” experience and its representation (my summaries of Morrison’s ideas and quotations are drawn mostly from the first book). The six representations he chooses make for a palimpsest, a multi-layered account of this place – “the Red Centre” is Morrison’s shorthand although it too is a construction – and its history. One account is chosen as a “literary snapshot” for each of the following historical phases: the precolonial era; the exploration era,1860-1911; an interwar period, ending around 1945; the Menzies era of the 1950s-60s; the Land Rights period, 1970s-80s; and finally what he calls the Intervention era, from the late 1990s to the present.

The precolonial walk – as recounted by Tommy Kngwarraye Thompson in “A man from the Dreamtime”* – Morrison characterises as a pilgrimage, a ritual practice, in part as a way to oppose the old pejorative idea of the Aboriginal “walkabout”.

By anyone’s standards it is an “epic walk”, from Kaytetye country (some 350 kms north of Alice) to Arabana country around Port Augusta, a distance of 1700 kilometres one-way. The walkers on the southward journey are Marlpwenge and his ‘wrong skin’ wife Nalenale (on the return journey she is replaced by a ‘right skin’ wife). The narrator, shifting from inside to outside the story, is sometimes the Dreamtime Ancestor Marlpwenge, sometimes the contemporary man, Thompson.

As they travel the walkers traverse the home country of other language groups, which allows Morrison to reflect on the Kaytetye (and by extension Aboriginal) sense of place, home and borders. In contrast to the hardened settler frontier, which is resistant to inter-cultural exchange, Aboriginal language group borders are “porous”, to use his term, with ‘a way of being’ shared by groups on either side.

The Dreamtime journey maps “a geography of survival”, physical as well as social / cultural, across these territories. Thompson’s retelling – sometimes using postcolonial place names and referring to the railway, roads, camel journeys, for example – also accounts for historic change, countering the cliché of a timeless culture.

The practice by Aboriginal people, both of walking these ancient trade routes that were also spiritual pathways and of telling the stories of these journeys, is a networked imagining of place and an articulated geography of home, writes Morrison – “an entire universe” of which settler Australians are largely ignorant.

The practice by Aboriginal people, both of walking these ancient trade routes that were also spiritual pathways and of telling the stories of these journeys, is a networked imagining of place and an articulated geography of home, writes Morrison – “an entire universe” of which settler Australians are largely ignorant.

Right: Walking the talk, Glenn Morrison leads a “storied walk” along the Todd River during this year’s Alice Springs Writers Festival. With him are two of the story-tellers, Veronica Perrurle Dobson and Fiona Walsh.

Into this space, with no concept that such representations might even exist, journeyed the explorer John McDouall Stuart. Every step he took in his multiple attempts to cross the continent from south to north (successful on the sixth attempt in 1862) was up against the frontier, as he saw it, away from home (settlement) and into a primitive wilderness (though one that yet might yield the prospect of a future home / settlement).

The arduousness of his journeys is the stuff of legend, which is Morrison’s point. Their representations in Stuart’s journals as the struggle of (civilised) man against (primitive) wilderness reinforces the dominant myth of Australian national identity and serves also to hide the expropriation of Aboriginal land.

In the journals Aboriginal people are represented mostly by absence, although occasional observations – for instance of their footprints, their signal fires, and, at Attack Creek, their fighting skills – yield “a momentary glimpse across the frontier”.

Overall though, Stuart was in this environment for too brief a time to make much sense of it, says Morrison: it remained for him a harsh wilderness, unforgiving, difficult, awaiting transformation: “In this way, Stuart anticipates generations to come of outsider travel writers who are equally ill-equipped both materially and culturally to faithfully portray the complexity of the Centre.”

In contrast TGH Strehlow’s Journey to Horseshoe Bend, not written till a century later but recounting events of 1922, evokes a Central Australian place – along the Finke River between Hermannsburg and Horseshoe Bend – with “all the intimacy and reverence of home”.

This text, presented as a novel, is really a memoir, telling from the point of view of Theo, the 14-year-old TGH, the story of his father’s last journey and ultimate death. In it the frontier is permeable: narrating his “lifeworld”, Strehlow, born and raised at Hermannsburg, is insider and outsider in one, delivering a European view of the landscape and an Aboriginal description of Country, something new in Australian literature.

While he may have been co-opting cross-cultural ideas to construct “a map of himself” (serving to validate controversial actions of his later career), Strehlow’s text also maps a way forward for settler depictions of place, says Morrison, for a literature of “inhabitation”, embracing the Centre’s “postcolonial complexity” and confronting “its hegemonic representation as a divided frontier”.

This way forward, however, was not yet in the public domain when the next account considered by Morrison was published. This is Arthur Groom’s I Saw a Strange Land, published in 1950, recounting the author’s experiences of the Centre, including prodigious bushwalks, in 1946.

This way forward, however, was not yet in the public domain when the next account considered by Morrison was published. This is Arthur Groom’s I Saw a Strange Land, published in 1950, recounting the author’s experiences of the Centre, including prodigious bushwalks, in 1946.

Left: Participants in the “storied walk” going into the dry river bed at Middle Park, half way between the town centre and the Telegraph Station. Mrs Dobson was waiting there to speak of this home place for her family as she grew up.

Groom’s concern was to make a case for protecting the Centre’s “wilderness” and its Aboriginal people; he sought to convert the strangeness of both from liability to asset, arguing for turning large tracts of land into conservation zones. What he saw in his Strange Land was not Stuart’s “great unknown”, but a managed version of nature, which a tourist can experience.

His conservation goal may have had merit, but his opposition of wilderness to civilisation, of escape to home, is a binary representation, a re-inscription of the frontier, argues Morrison, and is inadequate to capture the “patchwork political geography” of the Centre. The presence of Aboriginal people, whom Groom encountered at Hermannsburg and Areyonga, should have worked against his idea of wilderness, but they remained for him mysterious and inscrutable; there is no notion in his text of the landscape as Aboriginal homeland.

Better than ‘frontier’ as a way of representing the Centre is the concept (originally advanced by Mary Louise Pratt) of a ‘contact zone’ – “much richer and loaded with possibility”, as Morrison writes. While the frontier manifests sporadically in Bruce Chatwin’s best-selling The Songlines, the book is markedly more open in its sense of place in ways typical of a contact zone: writing of Alice Springs and the Centre, it renders a zone of “culture old and new, foreign and home-spun, ancient and modern”.

First published in 1987, The Songlines is the text that Morrison considers in the context of the Land Rights era. Like Strehlow’s, Chatwin’s text is also presented as a novel, although it too is memoir-like, tracing through its narrator Bruce two journeys in the Centre Chatwin undertook over nine weeks in the 1980s. Unlike Strehlow, Chatwin was an outsider but fiction allows him to render an insider’s view (informed by interviews) through his like-minded character Arkady, a non-conformist intellectual and tireless bushwalker who works as a go-between with Aboriginal people.

The book has been fiercely criticised in some quarters, but it took to a huge audience an understanding of “particular geographies”, inscribed by the songlines – a term Chatwin coined for the Dreamtime walking routes – as the home of Aboriginal peoples. It also leaves the way open for an intermingling of cultures, defusing, writes Morrison, “constructions of Central Australia as a frontier, [which has] enormous implications for Australian identity”.

After all this it is a bit deflating to come finally to the text Morrison studies as a reflection of the Intervention era; indeed it is deflating to realise that ‘Intervention’ is the label he gives, not without reason, to this moment we are living in. The text he studies is Eleanor Hogan’s Alice Springs and in particular her second chapter, “The Gap”, where the author goes for a walk between her apartment and the neighbourhood supermarket (not exactly an “epic walk”).

In Morrison’s analysis, the text reveals a hardening of the frontier, a further distancing of the Centre from ideas of home: “A sense of home is masked by a politics of suffering and disadvantage, which is privileged over other aspects of place and identity. This representation of frontier counters recent evidence, especially in the arts, of increasing intercultural exchange,” he writes. (Here he references my commentaries, including The Fertile Space Between Us, but could have mentioned also the very on-topic The Long Weekend in Alice Springs by Craig San Roque, both the essay and the graphic novel adapted from it by Joshua Santospirito. It is strangely missing too from his reading list on the Red Centre, as is my pertinent book, Trouble: On Trial in Central Australia.)

Morrison is critical of Hogan’s choice to not engage in discussions of Aboriginal culture. This reconstructs the frontier, as does her reinforcement of popular media perceptions of Aboriginal people as victims lacking agency while, on the other hand, demonising white people. All this is inadequate to account for the more nuanced “lifeworld” of Alice Springs, he writes.

Because her focus is so much on the impacts of alcohol, Hogan’s Alice Springs, despite its title, “does not produce a narrative of place,” says Morrison, “so much as a political geography of a particular issue”.

Because her focus is so much on the impacts of alcohol, Hogan’s Alice Springs, despite its title, “does not produce a narrative of place,” says Morrison, “so much as a political geography of a particular issue”.

Left: Morrison introducing Pat Ansell-Dodds, the fourth story-teller of his “storied walk” along the Todd, concluding here at the Old Telegraph Station. It was the enforced ‘home’ of members of the Stolen Generation, including some from Mrs Dodds’ family.

Given all this interesting reflection on how the Centre is and has been represented, and his well-argued case for a more open sense of place than the frontier idea allows, it is reasonable to examine from this point of view Morrison’s own narratives. These are found in his second book as short accounts (of a few pages) to orient the reader to each of his selected texts.

It speaks to the strength of the frontier mentality that one so attuned to recognising it as Morrison can also fall into it. For example, the opening pages of his chapter on Strehlow are written very much as an outsider looking in, from quite some distance at that. He drives to Hermannsburg from Alice Springs, pressed for time (he has one morning). He gives a neat enough observational description of what he sees in a quick tour of the community, but interacts with no-one.

Most surprisingly, he weaves into this a background commentary focussed on what he says is the community’s “well-known propensity for violence”. This is stated baldly, without citing any specific examples, any sources or offering any insights (indeed he says he has “no answers”). The only person quoted is Heidi Williams, the non-Aboriginal former wife of Warren H Williams (the quote is excerpted from an interview she gave as an election candidate to Erwin Chlanda in these pages).

As he strolls through the Strehlows’ house in Hermannsburg’s historic precinct Morrison feels haunted by the spectre he has set up, of a ravaged culture under “assault” from modernity, its people “driven and at the same time frozen by localism, standing at the eye of an ideological cyclone”. A florid frontier indeed.

In Alice Springs, where he has lived for almost two decades, he writes effectively (introducing Chatwin’s text) of his ‘embodied’ experience on a warm humid day, walking between Olive Pink Botanic Garden and the town centre, but again he doesn’t do much better on encounters with Aboriginal people: he calls hello to an Aboriginal man on the street, laughs with him when he coughs on the inhaled smoke of a cigarette; he describes an Aboriginal woman “hawking her paintings to diners” at a Todd Mall cafe, while a tourist reaches “nervously for her handbag”.

In introducing Hogan’s text, he has a more extended encounter, with a middle-aged Aboriginal woman called Rosie: she has been stabbed by her daughter’s husband. He writes matter-of-factly about Rosie and her predicament in contrast to Hogan who tends to project a lot onto her encounters, but there is nothing in his own writing here which really runs counter to Hogan’s frontier.

I am not quibbling here, this is important. I think Morrison would consider it important, but it can be hard to see clearly what one’s own writing is doing. However, this criticism goes for writing that is a small fraction of the sum of his work and it does not overshadow the significant contribution of his two books.

__________________________

*Published in Growing up Kaytetye, Jukurrpa Books (IAD Press), 2003, stories by Tommy Kngwarraye Thompson compiled by Myfany Turpin.

Well considered review Kieran and good on you Glenn. I very much enjoyed reading the PhD and expect the new book will see a much bigger audience get the chance to appreciate your writing talents.