Namatjira family's struggles and triumphs

28 July 2017

Archived article

By KIERAN FINNANE

By KIERAN FINNANE

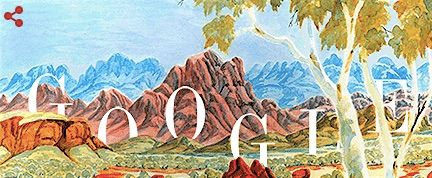

For today only Australian googlers will be reminded of the anniversary of the birth of the artist Albert Namatjira, 115 years ago. When you go to the search engine’s page, “the Google Doodle” is a painting in the Namatjira style by Gloria Pannka.

Google approached Pannka through the Iltja Ntjarra Many Hands art centre, following the launch in Canberra of the Namatjira Legacy Trust in March.

By happy coincidence the multinational giant’s acknowledgement comes just ahead of the premiere at the Melbourne International Film Festival of Namatjira Project, a feature-length documentary tracing the story of the Namatjira family over five generations and “their fight for justice”.

This fight relates particularly to the situation with Albert Namatjira’s copyright. Since 1983, when the copyright was sold to John Brackenreg of Legend Press, his descendants have earned no money from copyright or royalties from reproductions of their famous forebear’s works.

When the arts for change company Big hArt became involved with the family more than five years ago, they began negotiations for the return of the copyright. These have proved fruitless and now they are looking at legal options, strengthened by the acknowledgement in the media of the Public Trustee at the time that sale of the copyright for 50 years (to 2029) was a mistake.

According to ABC Radio National’s Awaye!, the former trustee, John Flynn, is adamant that a full sale for the entire life of the copyright was never discussed during negotiations with Brackenreg.

“But any dealings I had with Legend on the phone or by correspondence — if my memory is correct — was only for the seven years,” he told Awaye!

This has opened up the legal possibilities, says Big HArt’s Sophia Marinos who will travel with Pannka and Lewina Namatjira to Melbourne for the premiere of the film, of which she was the producer.

This has opened up the legal possibilities, says Big HArt’s Sophia Marinos who will travel with Pannka and Lewina Namatjira to Melbourne for the premiere of the film, of which she was the producer.

Right: Sophia Marinos (right) with Gloria Pannka and Bianca Gonos, also in the Big hArt team.

Lewina’s presence is important: a big part of the focus of the Namatjira Project has been to bolster the continuity of the tradition, supporting the passing on of skills to the younger generations: Lewina is not an artist yet but she is “learning to paint”, says Pannka.

Meanwhile, the Namatjira Legacy Trust has raised $45,000 towards supporting the artists and their goals – “It’s a start”, says Marinos.

“We’ve achieved a groundswell of exposure, which is having a trickle down effect, the whole reason we have been doing this project.”

That is being felt at Iltja Ntjarra Many Hands with heightened interest in the art, including acquisitions by state galleries, and new opportunities for the artists, including workshops in skills such as printmaking and photography.

The Melbourne launch of the documentary will be followed by screenings at the Brisbane International Film Festival and the Darwin Art Fair. Theatrical release to follow will include a season at the Alice Springs Cinemas, starting 7 September.

The Melbourne launch of the documentary will be followed by screenings at the Brisbane International Film Festival and the Darwin Art Fair. Theatrical release to follow will include a season at the Alice Springs Cinemas, starting 7 September.

Left: Albert Namatjira with his wife Rubena, some grandchildren and father Jonathon. Gross Collection, courtesy Strehlow Research Centre.

Director of Namatjira Project is Sera Davies. Below is an extract of her statement about the film:

“On one level, this film acknowledges all the stuff of grand whitefella narratives; exoticism and genius and art, cultures clashing and connecting, unthinkable malice and the quest for justice, all threaded into one life.

“Albert’s story plays right to the heart of our preoccupation with telling a particular type

of narrative; our making of an unlikely hero, our impossible demands upon them, our destruction of them when they fail to meet our expectations, our saying sorry about it.

“On another level though, [the film] challenges this singular monocular representation of Albert’s legacy and examines the enduring impact that this type of representation has for current generations of the Namatjira family. It’s our gaze through the single story that ultimately killed Albert and continues to present dire implications for contemporary inter-cultural relations.

“This documentary questions the permissions that we on the east coast have given ourselves to play out this singular tragedy story again and again, and does so by positioning the story in alternate and little explored spaces for us to sit together.

“It’s this Aranda concept of ‘nama’, or sitting side by side in learning and observation, that was demonstrated in the unique friendship of Rex Battarbee and Albert Namatjira. Through their friendship, we are afforded an opportunity to witness the first learnings from a rich dialogue that has forged new pathways into contemporary inter-cultural collaboration.

“The longitudinal and observational framework of the film allows multiple and sometimes conflicting truths to present themselves equally in intimate and honest moments of genuine exchange. This process comes right from the engine room of how this company Big hART operates, to a simple yet powerful ethos that ‘It’s harder to hurt someone when you know their story’.”