Birth of an art movement: the untold story

23 June 2017

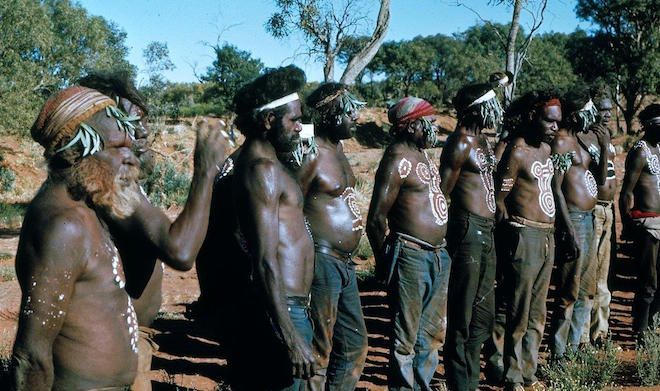

Above, ceremony time, west of Papunya in June 1972, from left: Tutuma Tjapangati, unknown, Ronnie Tjampitjinpa, unknown, Jimmy Wanatjukurrpa, Nosepeg Tjupurrula, unknown, John Tjakamarra, unknown, Walter Tjampitjinpa. Image: Llewellyn Parlette, from his personal collection.

By KIERAN FINNANE

The flame of the Western Desert art movement was lit in West Camp, the Pintupi enclave at Papunya, well before school teacher Geoffrey Bardon arrived in the settlement in 1971, although he is rightly acknowledged for fanning that flame.

This story-changing account of the movement’s origins emerges from a major exhibition, Tjungunutja, opening next weekend at the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory (MAGNT) in Darwin. It brings together paintings, photographs, and film from the earliest years of the movement, many not seen since that time, some never seen in public before.

The very title reflects the revision of the foundation story. It means “from having come together”, referring to the punyunyu – ceremony for novices – conducted at West Camp, starting in the warm months of late 1970.

The Old Men of the settlement – not only Pintupi but Anmatjere, Luritja, Arrernte, Warlpiri, and Pitjantjatjara – mounted the punyunyu as “a challenge”, says Bobby West Tjupurrula, one of the next generation artists who has worked on the curation of this exhibition.

The challenge was to see “who’s got the strongest law and culture”, a way of engaging the troublesome young men of the era in what West, then just a boy, describes as something “like university”. It was only after many months of intense cultural transmission that everyone agreed – they all had strong law and culture, they were “all equal, all the same”.

The challenge was to see “who’s got the strongest law and culture”, a way of engaging the troublesome young men of the era in what West, then just a boy, describes as something “like university”. It was only after many months of intense cultural transmission that everyone agreed – they all had strong law and culture, they were “all equal, all the same”.

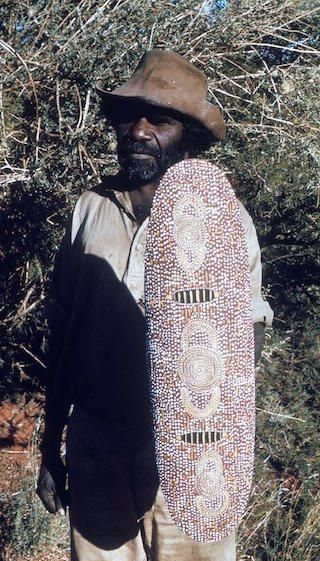

Right: Johnny Warangula Tjupurrula holding a kuditji, west of Papunya, June 1972. Image: Llewellyn Parlette. The kuditji, collected by Parlette and on show at Tjungungutja, shows the tracks of an ancestral wallaby as it travels between water sources, stopping for ceremonies on the way.

It was out of this experience that the painting came, says West: “When they finished their business, they started giving them story, Tingarri, all that one, giving to them to keep it in their mind … From that they started painting … ‘So, ok, I’m going to give my canvas to my son, he can sit down and paint.’ ‘I’m going to give my son too.’ That’s what they said in Papunya.”

Perhaps it has taken joint curation with senior Aboriginal artists and leaders from the region to revise the origins story. Even the artists’ own company, Papunya Tula, represents Bardon, a non-Aboriginal man from New South Wales, as the instigator: the movement began in 1971, according to their website, “when a school teacher, Geoffrey Bardon, encouraged some of the men to paint a blank school wall”.

In the hands of the curation team, working together over more than two years, Tjungunutja tells a different story, a story of grandfathers, for grandsons. Apart from West the curators are the surviving first generation artist Long Jack Phillipus Tjakamarra, next generation artist Michael Nelson Tjakamarra, senior Luritja man Sid Anderson, and MAGNT’s curator of Aboriginal Art, Luke Scholes. Supporting them have been Desmond Phillipus Tjupurrula (son of Long Jack) and artist Joseph Jurrah Tjapaltjarri.

Their own younger generations are the primary audience for the show, says West: “We want to take young people to Darwin, the kids, all the young ones, because all the old people all gone, they finish, pass on.

“We need to encourage young people to continue telling a story, and showing them.”

Thus the exhibition, its content and its installation, first and foremost had to make sense for them, says Scholes, and it was early decided that hearing their languages, seeing their country and communities, and hearing directly from the artists’ descendants (on film) will be as much part of the experience as the highly anticipated paintings, archival photographs and film, and historic ephemera.

Scholes with filmmaker David Nixon supported by Shane Mulcahy spent almost a month in two stints in Papunya, Kintore and Kiwirrkurra, collecting some 28 hours of oral histories from the descendants. Some such as Eunice Napanangka Jack, daughter of Tutuma Tjapangarti, are now reputed artists themselves. Their stories are integrated into the exhibition, not simply available as a supplementary resource. Speaking in their languages, they recall the early years of the art movement as well as life generally in the communities, as it was then, as it is today.

Scholes with filmmaker David Nixon supported by Shane Mulcahy spent almost a month in two stints in Papunya, Kintore and Kiwirrkurra, collecting some 28 hours of oral histories from the descendants. Some such as Eunice Napanangka Jack, daughter of Tutuma Tjapangarti, are now reputed artists themselves. Their stories are integrated into the exhibition, not simply available as a supplementary resource. Speaking in their languages, they recall the early years of the art movement as well as life generally in the communities, as it was then, as it is today.

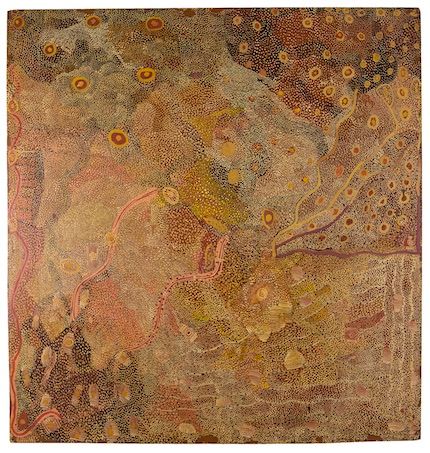

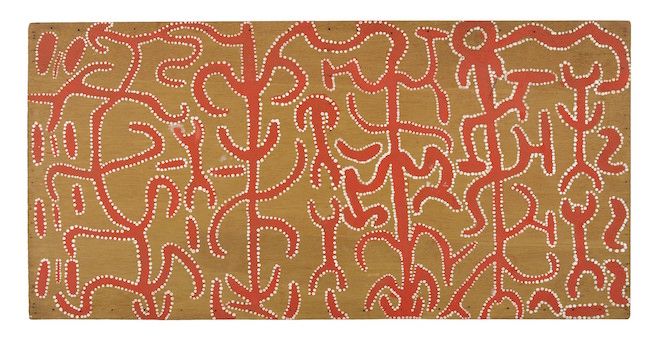

Left, immediately brilliant: Johnny Warangkula Tjupurrula, Water Dreaming, 1971. Collection of MAGNT.

This is particularly what sets this exhibition apart, says Scholes, the missing ingredient of most accounts of the movement, whether in exhibitions or books: “The story is not told in their words.”

“They need to listen, all the tourists,” says West, “to understand properly, how they been living in their communities for a long long time and using painting and other things.”

The paintings are drawn from MAGNT’s rich collection of 220 early works, about half of them presciently acquired by the museum’s director Colin Jack-Hinton in 1972 and the rest by 1980 (with five more added later). They are mostly on boards, often discarded building materials that the artists picked up around the settlement.

After limited showing in the early years, much of the collection remained in storage because of the sensitive cultural content of some images. This issue has been resolved following careful consultation, through the Aboriginal Areas Protection Authority, with the relevant senior Aboriginal men. They have restricted some 60 images, while of the rest, 128 have been chosen for showing in Tjungungutja.

Helping to tell the story are photographs and footage of the era. Of particular interest will be the record made by Llewellyn Parlette, an American anthropology student who did his Masters research in Papunya from June to October in 1972. This material, unearthed by Scholes, had never been seen in the Western Desert before, let alone in public.

Scholes’ intensive research in the archives has also shaped his long essay published in the exhibition catalogue, setting the movement’s beginnings in their broader Northern Territory context. Although he acknowledges Bardon’s impassioned contribution, he reveals facets of the story that Bardon’s own accounts have obscured and at times misrepresented.

For example, there was significant administrative support for arts practice at Papunya both before and after Bardon’s arrival in February 1971. The production and sale of artefacts and paintings was a “private enterprise venture” worthy of “fostering”, reported settlement superintendent, Warren Smith in mid-1970.

For example, there was significant administrative support for arts practice at Papunya both before and after Bardon’s arrival in February 1971. The production and sale of artefacts and paintings was a “private enterprise venture” worthy of “fostering”, reported settlement superintendent, Warren Smith in mid-1970.

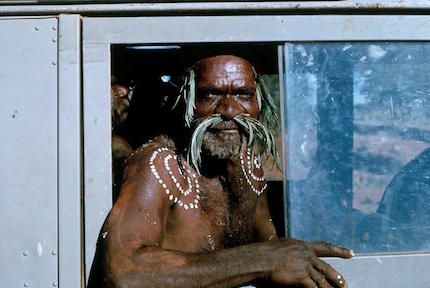

Left, the deep satisfaction of ceremony: George Tjangala afterwards, Warren Creek, June 1972. Image:Llewellyn Parlette.

In the following year Bardon certainly championed the painting of the murals on the walls of Papunya School, till now the moment hailed as the foundation of the movement. Smith’s successor Laurie Owens, responding to the “very striking” work showing “dreaming symbols”, referred to a “very generally felt artistic awakening among the population here”. The impression is of something happening on a broader scale than simply amongst Bardon and the painters. The appreciative nature of the comment is also in contrast to the overwhelmingly negative account of the administration left by Bardon.

A very active supporter of the movement was District Welfare Officer Jack Cooke, who wasted no time in entering Kaapa Tjampitjinpa’s Gulgardi in the Caltex Northern Territory Art Award in 1971. It famously was co-winner of the award, an event always presented as a breakthrough, in part due to Cooke himself who believed it was the first time an Aboriginal artist had entered the award. However Scholes reveals that bark painters from Arnhem Land and watercolour artists from Hermannsburg had been regular entrants in the award for years and in fact joint-winner in the previous year was a Kuninjku bark painter. In 1971 nearly a quarter of the 68 entrants were Aboriginal.

Among those who snapped up other Kaapa works Cooke had brought with him to Alice Springs was Harry Giese, then director of Welfare in the NT Administration who bought the painting for the collection of the Department of Aboriginal Affairs. All this suggests quite a different context for the reception of Aboriginal art in the Territory than has been generally assumed.

Cooke continued to promote the artists and the formation of their company, Papunya Tula Pty Ltd. He helped plug the gaps left by Bardon’s frequent absences and erratic business practices, as did Pat Hogan, the Alice Springs art dealer who took the earliest consignments of work and promoted opportunities for the artists, and Mary White, an advisor on Aboriginal projects to the Craft Council of Australia. White has been virtually unacknowledged in all previous accounts but she provided much practical support and guidance to Bardon and the artists.

However, the big story of what happened at Papunya and that Tjungungutja celebrates is the resilience of Aboriginal law and culture and the brilliance and determination of the artists themselves in presenting it to the world.

Note: MAGNT is committed to eventually bringing Tjungungutja to Alice Springs but this may not be for another few years. It shows in Darwin until 18 February 2018.

Below: Charlie Tjaruru Tjungurrayi, Medicine Story or Man Dreaming, 1971, collection of MAGNT.

That’s a great story, people at the exhibition will love it.

But a “coming together” at Papunya spawned the art movement?

The Pintupi were the outcasts there, referred to as “rubbish Pintupi”.

They were traditional (considered backward) when the other groups were rapidly adopting the skills needed to fit into the Whiteman’s world.

The administration burnt their spears in a public ceremony aimed at humiliating them.

It didn’t help that Papunya was not their country, they were trespassing on Arrente land.

Their leadership had been devastated in the 1960s.

In 1964 half the people who came in from the desert were dead within six months.

West Camp was squalid and infectious diseases ravaged the Pintupi living there.

The administration kept away from it, describing it as a heath hazard (for themselves).

Pintupi resilience was shown by moving away from Papunya, to Waru Wiya and Ya Ya and finally to Kintore in 1981.

While at Ya Ya they were often precluded from the benefits at Papunya such as food, because the administration there wanted them to return rather than assist their autonomy.

It was at Ya Ya that the art movement flourished, the Pintupi had no official support and were desperate for food and vehicles.

Art provided one of the few sources of income.

Ian Dunlop’s film shot at Ya Ya in 1972 provides a first hand description of the art movement facilitated by Bardon.

Whereas at Papunya official support for art was often directed away from the Pintupi, Bardon recognised their genius and focused on them.

The art movement has its roots in Pintupi autonomy and resilience in the face of adversity and discrimination.

Ralph, I appreciated reading your response.

It is interesting who government authorities acknowledge and discredit, and why this is so.

I comment on my comment. Interesting should be replaced by infuriating – very very sad. Very very destructive.

Ralph, Thanks for your comment although I’m not sure that any of what you say contradicts the account of the Aboriginal curators. In the article I have quoted Bobby West Tjupurrula from the interview I did with him on the instigating spark for the movement. Here is how he puts it in the catalogue:

“Pintupi people were having a hard time at Papunya. There was a lot of fighting, a lot of arguments and they wanted that to change … The Pintupi men wanted to show people in Papunya that they had really strong law, Tingarri. … They were giving it as a gift, that Tingarri. Warlpiri, Luritja, Anmatyerr, were watching, waiting for their turn …

“After that, after Tingarri, that’s when they did dot painting, body painting. Then they did that [Honey Ant] mural at the school, made it public, letting everyone know they were all together.”

In 1999 Turkey Tolson Tjupurrula gave a similar account to Paul Sweeney of ‘big ceremonies’ just before Geoffrey Bardon’s arrival:

“All the tjilpis in one place, big mob of old men teaching us. Not only Pintupi; there was Warlpiri, some Arrernte.”

Tolson’s account is quoted by Vivien Johnson in her book Streets of Papunya: The Re-invention of Papunya Painting (pp 64-5) when she is considering reasons from an Aboriginal perspective that Papunya people might have had for picking up their paintbrushes.

Bardon himself acknowledges this impetus for the murals in his 2004 account: “These murals as conceived by the Western Desert people, as I was to find out, were to satisfy an Aboriginal community split quite dramatically between tribal groups.” He characterised the ceremonies that had taken place as having required “a compromise between the Anmatjira, Aranda, Pintupi, Loritja and Warlpiri forms” and similarly the appropriateness of the murals had to be negotiated “between the four tribal groups at Papunya”. (Quoted by Johnson, p65)

Diane, Bardon’s invaluable contribution to the movement is acknowledged by the curators. The challenge I have highlighted is to his primacy as an instigator. In that story, the emphasis of the Aboriginal curators is on their own cultural processes. Luke Scholes’ essay gives a detailed account of Bardon’s role in his Papunya years, while also documenting the contributions of other non-Aboriginal people.

I don’t think any of the curators of this exhibition can be seen to be responding to an agenda of “government authorities”.

The DVD Mr Patterns [Geoffrey Bardon] 2003 directed by Catriona McKenzie fills in some background from another perspective. Also Settle Down Country and Benny and the Dreamers DVDs provide some Pintupi historical background.

I’ve just spent some time visiting this exhibition, and Dave Nixon’s accompanying film deserves all the awards.

I can understand the confusion. My lineage is with the Mackinac tribe and yet more than half of us are recognized under the Sioux tribe.

I remember Johnny W who proudly exclaimed to be Warlpiri, pretending not to like the Pintupi, and yet loved the Pintupi, while later I found out, his mother was Pintupi!

Hope at some point to see this amazing exhibition!