The gaolers and the gaoled: new exhibition

16 May 2017

By KIERAN FINNANE

By KIERAN FINNANE

What’s it like to be in gaol? What’s it like to be the gaoler? What happened to the mentally ill in Alice Springs before there were any specialist services? How is it that , in a town that has destroyed much of its built heritage, we saved a gaol ? How does a women’s museum make sense of their role, housed in an old gaol?

These are among the questions for which the National Pioneer Women’s Hall of Fame (NPWHF) has looked for answers in its new exhibition, Relationships.

The museum began with a vision (Molly Clark’s) and soon a collection – of photographs, documents and a range of women’s objects – that became an exhibition, curated to tell the story of mostly European women’s experience in Australia, particularly Outback Australia. The exhibition opened in the Old Courthouse, opposite The Residency in Parsons Street, before the move to the Old Gaol – a heritage building looking for a new purpose.

The gaol setting though is far from neutral. Even without interpretation its story makes itself felt, quite distinct from that of the core NPWHF exhibition, and the excellent recent addition of What’s Work Worth?. There have been a number of one-off events that have reflected on the story of the gaol as a place of incarceration, including historian Megg Kelham’s reincarnation as Mrs (Bertie) Muldoon, a former gaol matron and wife of Its Superintendent, Phillip Muldoon, and last year’s series of performances, under the umbrella title Let me See.

Now NPWHF, under the guidance of curator Dianna Newham, is tackling the gaol story head on, laying the foundations of a new exhibition upon which they can keep building.

Now NPWHF, under the guidance of curator Dianna Newham, is tackling the gaol story head on, laying the foundations of a new exhibition upon which they can keep building.

Its title, Relationships, is sufficiently broad to take in everything from the gaol’s institutional history to the stories of individuals who have spent time there – prisoners, prison officers, visitors, the mentally ill – or who have shown an interest in it – journalists, heritage campaigners. What has been achieved so far makes for a thoroughly engaging visit.

Deeply moving are two sculptural works which inhabit two of the cells in what was formerly the women’s block. They stand in for the thousands of individuals who have been confined at the gaol for different reasons, and express two fundamental states: one is the desire to be free, the other is the prostration of suffering.

The sculptor is Sia Cox, known for her highly expressive soft sculptures and deep interest in the human figure and face.

One of the figures is perhaps Aboriginal and male, the other perhaps white and female, but each has a humanist breadth that allows the viewer to project other identities onto them.

There is a story that the relatives of Aboriginal inmates would stand on top of Billygoat Hill / Akeyulerre and communicate with those inside by hand signals. Cox’s dark figure stands on the tabletop bolted to the cell wall peering through the high window. The view might be to relatives beyond the gaol walls, but he/she might simply be seeking the consolation of sunlight, of sky, of a tree or a bird. She/he might be remembering life on the outside, or pondering the challenge of returning to it. These were some of my thoughts; you will have your own.

The white figure lies huddled on a chain-mesh bed frame. While the dark figure is tall and quite robust, this figure appears frail, even wasted, and is closed in on her/his anguish. The outside world is out of reach and appears out of mind. This could be a prisoner at a low ebb – full of remorse and regret, depressed, lonely – but the audio in this cell introduces the visitor to another possibility: this could be a person in mental health crisis, incarcerated because nobody knew what else could be done.

We learn from historian Megg Kelham that Alice Springs did not get its first mental health services until the 1970s. The prison officers hated having to take in a mentally ill person, she says, because they knew the illness was not a crime and the person’s distress could also upset the other prisoners.

We learn from historian Megg Kelham that Alice Springs did not get its first mental health services until the 1970s. The prison officers hated having to take in a mentally ill person, she says, because they knew the illness was not a crime and the person’s distress could also upset the other prisoners.

She says one of the gaol’s first “mad” inmates was a European man from a station, who had been exposed to mustard gas. What happened to him is not revealed, but there was no treatment available, no programs, as Tony Bohning, former superintendent, makes clear. Just observation, with the more extreme cases sent to South Australia.

Telka Williams, a past matron, recalls a personal friend in crisis who was brought in: she said “I’ve had my shock treatment, walking through that gate.”

Mrs Williams was compassionate but had no appropriate training. If it got “too tough”, a doctor would be called to give an injection.

She tells another poignant story of an Italian woman, with no English, who had arrived in Alice Springs for an arranged marriage but was rejected by the prospective husband. She had a complete breakdown and was eventually certified and sent to Adelaide: “To me it was heartbreaking,” says Mrs Williams.

This is the story that sticks to the prone figure for me: the whiteness, the ghost of her marriage hopes; the frailness, her feeling of being utterly abandoned.

In one of the larger common rooms, a Story Wall, designed by Elliat Rich, has been installed. It shows a range of objects, some of whose connection with the gaol is more immediately obvious than others. It’s worth sitting down here and again tuning in to the audio. A spotlight synced to the recordings picks out which object in the display they are referring to.

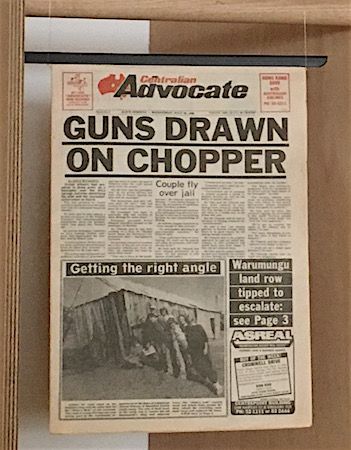

A front page of the Centralian Advocate is headlined “Guns drawn on chopper”; a subheading reads “couple fly over gaol”. The couple in question were Erwin Chlanda, then a freelance journalist stringing for commercial TV stations (who went on to establish the Alice Springs News), and a helicopter pilot. In the audio Mr Chlanda explains that he was doing a story for Channel Seven on the Territory’s high imprisonment rate and wanted pictures of the gaol as overlay.

The authorities declined to give him access so he hired the chopper and asked the pilot to fly over the gaol as low and for as long as he was comfortable. Hovering overhead while he got his footage, he could see the prisoners waving to him and the guards running. He later learned that they were arming themselves, even though they had recognised him as a local journalist, and were preparing to shoot.

The authorities declined to give him access so he hired the chopper and asked the pilot to fly over the gaol as low and for as long as he was comfortable. Hovering overhead while he got his footage, he could see the prisoners waving to him and the guards running. He later learned that they were arming themselves, even though they had recognised him as a local journalist, and were preparing to shoot.

“Journalism at the point of a gun!” – it made national headlines.

Another quite dramatic story is linked to a pair of glasses. It’s told by former Australian Senator Jo Vallentine, who came to Alice Springs to protest against the presence “in the living heart of our country” of the US spy base at Pine Gap. She was one of the first at the protest to be arrested and charged.

When she returned later for the court case, she protested her innocence, invoking the Nuremberg Principles of “a higher law than the law of the land”. Nonetheless, she was found guilty and fined but refused to pay. So she was sent to gaol.

Far from any special treatment being accorded her as a prisoner of conscience and an Australian Senator, she got the usual – the disinfecting shower, prisoner garb to wear, and all her personal effects removed, including her reading glasses and briefcase of papers. Without her glasses all she could read were the admonishing signs on the walls and the headlines of the few Women’s Weeklies lying around. She spent her time meditating and praying.

We hear again from Tony Bohning here, about “Bohning’s chain gang” – the prisoners who built the Larapinta Trail (the object on display is a brochure for the trail). Prisoners would vie for a spot on the team; there was never enough employment to go round, he says, commenting that the biggest problem confronting prison authorities is trying to “combat boredom and occupy minds”.

There’s also a liquor bottle displayed with a photograph of some men socialising that Mr Bohning speaks to. He comments on the “strong culture of drinking” among male and female prison officers, who became socially isolated “by virtue of the work” they did. They became callous, lost their compassion for people, he says. He found this sad, but rather than address the issues, they drank and toughed it out – they were “hard times”.

There’s also a liquor bottle displayed with a photograph of some men socialising that Mr Bohning speaks to. He comments on the “strong culture of drinking” among male and female prison officers, who became socially isolated “by virtue of the work” they did. They became callous, lost their compassion for people, he says. He found this sad, but rather than address the issues, they drank and toughed it out – they were “hard times”.

These insights into the gaolers, not only the gaoled, have stayed with me. More no doubt can be heard in the stories playing in the men’s cell block, which I have saved for a future visit.

My final stop on the day was in front of the DVD titled Save the Gaol, that runs on a loop in the old kitchen area. It was created by filmmaker David Nixon, with interviews and research by Dianna Newham.

In a little over 20 minutes it tells the terrific story of the concerted local campaign to save to Old Gaol from demolition, as the NT Government of the day intended.

When you see our local political representatives at that time – Alderman (later Mayor) Fran Kilgariff, MLA Peter Toyne – sticking their necks out, joining the demonstrations and the vigils; when you see the daring of some of the campaigners – Mike Gillam, Domenico Pecorari, “Radical Pensioner” Jose Petrick – you wonder where that strong civic feeling has gone. Is there nothing that warrants a determined fight anymore?

Something seems to be missing, that fire in the belly about shaping the town’s future, not being ridden over rough shod.

At least it was there in spades at that time and succeeded in saving the Old Gaol. We can be grateful to the brave campaigners that they did so, when so much else has been lost, and grateful too to the NPWHF, in particular Ms Newham and her collaborators, for finding ways to tell its story.

Below: Mike Gillam and Domenico Pecoraro coming back over the gaol wall after filming inside to prove the government of the day wrong in their assertions that the gaol buildings were beyond saving. With them is an ABC TV news cameraman. Waiting at the bottom to take the ladder was Jose Petrick, “Radical Pensioner”.

It’s ironic enough that a women’s museum finds itself in an old gaol but it’s all the more so given its appearance previously in an old courthouse.

The NPWHF’s occupancy of the Old Gaol highlights the long term chronic incoherence of the NT Government’s approach to heritage issues in Alice Springs, regardless of political persuasion.

When the NT Government (then CLP) announced in 1991 that a new gaol would be constructed south of Alice Springs, the initial intention was to preserve the Old Gaol. I suggested that the Spencer and Gillen Museum might be relocated there (subsequent to my earlier suggestion it be moved to the Araluen Centre complex), given that the NT Government had announced its imminent closure at the (then) Ford Plaza in April that year. My idea was enthusiastically supported by Roger Vale, the Minister for Tourism.

During the NT election campaign of 1994, the ALP promised to build a new home for the NPWHF at the Araluen Centre (reported in the Alice Springs News).

The CLP had a change of heart about the Old Gaol, deciding to demolish it to make way for hospital extensions and real estate infill development that had become all the rage in Alice Springs during the 1990s. While controversy raged over the fate of the Old Gaol, the NT Government also made plans to relocate the Spencer and Gillen Museum to the Strehlow Research Centre at the Araluen complex. The new Central Australian Museum was officially opened in August 1999, in conditions that have compromised the integrity of both the museum and the SRC.

Amongst those prominent in the clash to save the Old Gaol were Labor MLA, Peter Toyne, and then Alderman Fran Kilgariff (she was elected as mayor in 2000).

Yet when another heritage controversy erupted a few years later over the fate of the heritage-listed Rieff Building they were conspicuous by their absence.

Notwithstanding that the NT Heritage Council not once but twice affirmed the heritage significance of the Rieff Building, the Labor Government overturned its listing which was enabled by legislation passed by the previous CLP administration in the wake of its failure to destroy the Old Gaol.

The Rieff Building was destroyed in 2006, the same year the NPWHF was relocated to the Old Gaol (much to the dismay of its founder Molly Clark, I’m told). The opening of the NPWHF in its new home was supported with great fanfare from the NT Government, which announced that “The hall of fame will be the centrepiece of a first-of-its-kind tourism marketing plan for Central Australia” – a plan which subsequently fell into obscurity.

What would our country look like if government and corporations entirely had their way? Do these people never travel overseas and revel in the beautiful old historical built environments? I think how it took the NSW BLF to save the Sydney Public Domain behind the Opera House when developers in cohort with the NSW Govt were intent on destroying the space and the glorious fig trees. The historic Rocks area, even the grand Queen Victoria Building were destined for demolition! What is wrong with people when they get a little power? They can do a lot of permanent damage in their brief five minute tenure. A pox on many of them.

Somehow Kieran we saved the gaol when we got our act together after the bogan developers saw the quick buck before our town’s heritage, and destroyed much of our town. Alice certainly isn’t ‘A town like Alice’, and a million miles from the fictional Willstown in Shute’s novel.

What must tourists think when they arrive and find the rust bucket, The Plaza and now the Supreme Court? To add insult to injury there are forces to reopen Todd Mall to traffic and make fifty car parking spaces! Like that will change business fortunes. The Mall is for tourists who enjoy strolling when they feel safe. It’s really quite sad.

The saving of the Old Alice Springs Gaol was the last major win for our town’s built heritage.

It makes me laugh when I hear some blame the “conservationists” for stifling growth and bringing on the town’s present-day economic woes.

From my recollection, developers have won practically every heritage-related battle since that time, much to the detriment of our town’s once iconic Outback character.

And yes, there is still a fire in the belly of most of us from that time, but it is a slow burn, drenched in a sadness and disappointment that the system itself is stacked against our town’s heritage and that there are just so many times one can bash one’s head against a wall that just won’t budge.