Dick Kimber: premier scholar of Central Australia

12 May 2017

By KIERAN FINNANE

Many locals know him as the affable man who loves a yarn outside the post office, as well as the ‘go to’ on virtually any question of Central Australian history, black and white; some remember him fondly as a teacher from their high school days in the ‘70s; others still from his footy days with Westies, on the field and later, running water.

Not as many are aware of his scholarly contributions in the fields of ethnography, history, the deep past, linguistics, rock art, and contemporary Aboriginal art. He is Alice Springs’ own polymath, Richard G. (Dick) Kimber.

On a recent afternoon, scholars in all these fields and others who have known Mr Kimber professionally and personally gathered to acknowledge his life and work, evoked poetically by writer Barry Hill as a “Finke River of accomplishments flowing through this country”.

Many remarks concerned Mr Kimber’s prolific letter writing (the reason why he was so often encountered in the environs of the post office). ANU Professor of Anthropology Nicolas (Nic) Peterson could weigh his personal collection of Kimber letters by the kilo – he has five kilos’ worth, written in very small hand writing on very light paper. This is no ordinary correspondence between friends, but amounts to a “true treasure trove” of information, observations and references.

Neither has this kind of exchange been limited to Professor Peterson, which is why the National Library of Australia has put out a call for donations of Mr Kimber’s letters from all who have received them. Mr Kimber has already made available to the library some of his personal papers –120 archive boxes to date, including 50 boxes of research files on topics ranging from rabbits through solar cars to deaths in custody, and another 15 boxes of photographs.

Almost as soon as Mr Kimber arrived in The Centre – in 1970, taking up a post at the Alice Springs High School – he began travelling widely through the country, especially west of the highway, following his particular interest in Aboriginal people. This is where he first met Nic Peterson, who at the time was living in Yuendumu, studying Warlpiri ceremonial life.

We learned from Mr Kimber himself that his interest in Aboriginal people was sparked in childhood, in books and comics, visits to museums, and to the annual show in Barmera – a town in his native Riverland, SA – where he watched Aboriginal “warriors” in action in the boxing tent.

Later as a student he met Robert (Bob) Edwards AO, who would then have been a curator at the South Australian Museum, and he credited Dr Edwards as the greatest “formal whitefella influence” on his interest in Aboriginal people.

With Dr Edwards and Nic Peterson’s support, Mr Kimber became the first Sacred Sites officer appointed in the NT, a job he held for almost a year, including “three glorious months” of travel, in 1974. He went back to teaching for a while before he became coordinator for Papunya Tula Artists (1976-78).

In the meantime he had met Dr Margaret Friedel, a research scientist with the CSIRO, who became “not a footnote but a headline” in his life, as Prof Peterson said. They married in 1975 and five years later Mr Kimber resigned from the Education Department to care for their two young children, becoming Alice Springs’ first publicly acknowledged “house-husband”.

Above: Dick Kimber and Margaret Friedel with their children, Barbara and Steve.

Harold Furber – Arrernte man and member of the Stolen Generations, who spoke at the gathering about Mr Kimber’s interactions with Aboriginal people in town, including himself – was the first to question, laughingly, how well the children were looked after, noting that Mr Kimber’s house-husband duties coincided with an incredible outpouring of research and writing. Some support was given to this concern later by son Steve Kimber’s many funny anecdotes of his father’s benign neglect, delivering to him an “extremely rich” childhood, full of adventures. There was no hint of neglect though when Steve went off to university and his father faithfully wrote him two letters every week – accounting for 100 of the 500 or so written annually!

From an overview of the extraordinary span of Mr Kimber’s interests, Prof Peterson identified his three main areas of contribution – history, Aboriginal art and Aboriginal ethnography – and his most enduring work, Man from Arltunga – Walter Smith, Australian Bushman, a biography arising out of the meeting of these “two soul mates”. It is Mr Kimber’s only book yet he has written “volumes”, as Barry Hill noted, singling out for particular admiration the essays “Recollections of Papunya Tula 1971-1980″and “Tjukurrpa trails – A cultural topography of the Western Desert” (in Papunya Tula – Genesis and Genius) and “Politics of the secret in contemporary Western Desert art” (in Politics of the Secret). Their richness results from first hand knowledge, “acquired intimately, slowly, modestly”, said Mr Hill.

He spoke of Mr Kimber’s writing as characterised by “reverence” and “a sense of justice” to his material, by his “equanimity” of temper, by his command of everything that had been written before. He was a “custodian of nuances”. What mattered most was “men’s and women’s experience of being here”, which he worked to document and to quietly celebrate, acknowledging everything as “part of a greater whole”.

Mike Smith, a pioneering desert field archeologist, now an honorary Senior Research Fellow with the National Museum of Australia, spoke of the importance of Alice Springs nationally as an “intellectual bridge” between black and white Australians, in particular through its association with Hermannnsburg, the Strehlows, Albert Namatjira, Papunya Tula Artists, the Land Rights Act, the homelands movement, the handover of Uluru.

Above: Dick Kimber (3rd from left) and Margaret Friedel with event organisers Tom Griffiths (Professor of History, ANU), Mike Smith, and Steve Morton (scientist, Honorary Fellow, CSIRO).

Mr Kimber, as “a late 20th century version” of Frank Gillen, Mounted Constable Cowle, even the Venerable Bede, found himself as “the right person in the right place at the right time”. A warm, quiet observer, interested and non-judgemental, he often accompanied Prof Smith on his field trips, able to give good advice about who was who in the Aboriginal world and on the dynamics of interactions with them. Their correspondence has been voluminous, a monthly exchange over 25 years. Cross-indexed, Mr Kimber’s letters will become as valuable a resource as Frank Gillen’s, said Prof Smith. The collection might be titled “Just the briefest of brief notes”, his humble sign-off to his often lengthy letters.

In his work as a historian, what most distinguishes Mr Kimber has been his willingness to put forward an Aboriginal perspective, said Philip Jones, curator at the South Australian Museum. His “amateur status” has been a strength and particularly suited the context of his historical work, which often went against the grain in a small society, defensive about the past.

Unconstrained by academia he pioneered a composite approach to writing history well before it became widely accepted, drawing on the interplay between field observations, research in the library and archives, and the input of senior Aboriginal men and women. Behind his genial exterior, he had a “gimlet-eyed capacity to drill down into a subject, a true historian’s capacity to separate wheat from the chaff”, and he did so fearlessly. He had the temerity to question TGH Strehlow, for example, and no compunction in confronting new orthodoxies about fire regimes in Central Australia.

He was among the first to consider the possibility that European influences had begun affecting Aboriginal society before actual contact – through the acquisition of metal ahead of the frontier and the devastation of smallpox before Europeans appeared on the scene.

He paid attention to the way history enables us “to step away from the enmeshing effects of events and the sense of inevitability that they carry in retrospect”, contextualising the actors, white and black, searching for the motivations behind their actions.

He had an instinct for fairness. Dr Jones cited Mr Kimber’s chapter in a history of the 1894 Horn Expedition into The Centre, where he wrote of the initial encounter between Aborigines and Europeans as between two equal peoples. The fact that it was followed by misinterpretation on both sides was not the point; he was interested in how close they came to understanding one another and how far apart they were. In this he provided a model for historical research, which has inspired Dr Jones in his own work: it is crucial to see both sides of a story, to pursue all possible explanations.

He had an instinct for fairness. Dr Jones cited Mr Kimber’s chapter in a history of the 1894 Horn Expedition into The Centre, where he wrote of the initial encounter between Aborigines and Europeans as between two equal peoples. The fact that it was followed by misinterpretation on both sides was not the point; he was interested in how close they came to understanding one another and how far apart they were. In this he provided a model for historical research, which has inspired Dr Jones in his own work: it is crucial to see both sides of a story, to pursue all possible explanations.

Above: Philip Jones in discussion with Dick Kimber at Ooraminna in 2010.

Another feature of his work was his recognition of the opposing forces of conservatism and dynamism in Aboriginal culture, seen best perhaps in his analysis of the Western Desert painting movement and his work on the biographies of the principal artists involved. His approach shies away from the simplistic reading of the movement as the assertion of tradition and land-based knowledge in modern context.

Much of his understanding is based on face to face contact with the artists, travelling with them and “yarning” along the way. He also acknowledged the contribution to the movement of key external figures, not only Geoffrey Bardon, but Bob Edwards and the Aboriginal Arts Board, including its Aboriginal members. No serious student of the subject could ignore Mr Kimber’s contribution, which, as for the great majority of his work, was a “cogent gimlet-eyed analysis of received truths as much as new material”.

Dr Jones praised Man from Arltunga for the way it shows “all the shades of light and dark of a complex life history”, and Mr Kimber’s work on biography was the subject of many reflections during the afternoon and the next day, in a smaller gathering to discuss possible Central Australian contributions to a forthcoming Australian Dictionary of Indigenous Biography. Mr Kimber has contributed an exceptional 20 entries to the Northern Territory Dictionary of Biography and four to the Australian Dictionary of Biography, many of them notably the biographies of Aboriginal people, “uniquely important” in Australian scholarship and life, as noted by Mr Hill.

There is not room here to outline all of the acknowledgements made on the day. I reproduce below, however, the text of the talk that I gave, because it concerns Mr Kimber’s contributions to the Alice Springs News as a way of reflecting upon his role in the public life of our town.

DICK KIMBER’S ‘REAL TRUE HISTORY’ AND CONTEMPORARY ALICE SPRINGS

This image, painted in 2012, is by the late Alice Springs artist, Iain Campbell, who had no peer in the visual arts for his decades-long penetrating observations of the built environment of the town and the settler culture that played out in it and through it. You may recognise the phone boxes outside the post office and it is indeed Mr Kimber’s reputation for yarning outside the post office that is referenced in the painting’s title. It’s called, ‘That’s not Dick Kimber!’

Apart from the joke, the title immediately begs the question – well, who is it, this man in the blue shirt? I immediately read him as an Aboriginal man – the narrow hips, the slender long line of his legs, the hunch of his shoulders, as well as the fact of making a call from a public phone box in this time of en masse take-up of mobile phones (including by many Aboriginal people).

It is the only time, in more than four decades in Alice Springs, that Iain Campbell painted an Aboriginal figure. His title is an oblique way of recognising this, that he painted his familiars, his family and friends – and Dick Kimber and Margaret Friedel were close friends. He painted his colleagues (there’s an unusual body of paintings from the workplace) and the people who moved in his own quite broad social circles, particularly at the town’s various pubs, clubs and bistros and in the activities associated with them, such as lawn bowls and horse-racing. Not to mention the drinking.

In all these settings, Aboriginal people are distinctly absent. But, as this painting observes, they are there in the street, un-familiars, at the edges of the settler population’s vision. With it Iain Campbell rendered a certain truth about the separateness in ways of living of Aboriginal and other residents and visitors to Alice Springs.

This, however, is far less true of Mr Kimber than of most others. At the post office, for instance, the people he may be yarning with are as likely to be Aboriginal as otherwise.

In the public life of the town, he has been able to put this familiarity, that is personal and long-lived as well as deeply researched and thought about, towards a better understanding between the cultures. The examples are no doubt legion, but I will draw on the ones that I am familiar with, that are based on his contributions to the Alice Springs News, that Erwin Chlanda established back in 1994, and that he and I have kept going ever since. And even then I won’t attempt to be comprehensive.

The most profound would be the series about the Coniston massacre, titled ‘Real True History’, that Mr Kimber timed for the event’s 75th anniversary. The whole text came close to 40,000 words. Given the page constraints of our printed newspaper at that time, we published it in 18 parts, from September 2003 into the following year.

Above: One of the images used in Part 1 of the Coniston series, showing “Natives” on the Granites Track. Source: C.T. Madigan, Central Australia (Oxford University Press, 1944.)

The anniversary was marked by a commemoration, organised by the Central Land Council, out at Coniston itself. Many townspeople, white as well as black, made the journey, but Mr Kimber’s interest was to also bring the troubling history of the massacre right into the mainstream of Alice Springs public life. He chose a mass distribution medium for publication – in those days and up until 2011 the Alice Springs News was a printed newspaper and was delivered into every letter box in town by a team of mostly children. But Mr Kimber’s ability to communicate with a broad public arose from a number of his unique qualities and experiences.

As I see them, apart from his deep enquiries into the history of the region, these qualities were rooted in his warm, non-judgemental sociability across many parts of the community out of which he arrived at a tone in his writing that avoided raising hackles. Some might argue that hackles needed to be raised but when that happens, people tend to stop reading, or at least to stop thinking. The discussion becomes purely reactive.

The point came up acutely in relation to a caption that I wrote for a photograph of Constable George Murray, who led the retributive posses against Aboriginal people following the death of Fred Brooks on Coniston Station. I described him as a “mass murderer”. Before the next instalment Mr Kimber checked me on this. What was to be gained? The whole point of his carefully laid out story-telling was to allow people to enter into the matter, into the context of the times, examine the evidence and think through to conclusions for themselves.

Looking back, I can see how it was a lesson I took from him when it came to writing my book about more recent troubling violent events as revealed during legal proceedings in the Alice Springs courts. It taught me about finding a way to respect the facts, in so far as we can know them, while remaining in touch with the people and places I was writing about and for. A strategy for shedding light but not heat.

The Coniston massacre story was not the only time Mr Kimber injected this kind of even-tempered approach on contentious topics that were being aired in town and through the Alice Springs News.

He did the same when controversy erupted over the naming of Willshire Street after Mounted Constable Willshire. This had been stimulated by the broadcast of the SBS series, First Australians. Erwin Chlanda didn’t beat around the bush in his opening question.

He did the same when controversy erupted over the naming of Willshire Street after Mounted Constable Willshire. This had been stimulated by the broadcast of the SBS series, First Australians. Erwin Chlanda didn’t beat around the bush in his opening question.

NEWS: Was Willshire a murderer as stated in the series?

The answer typically lowered the temperature.

KIMBER: He was a complex character. Although he did not do the shooting, I believe that he would be accused of murder today, as he was then. Let me put him into a bit of context at the time of his trial.

And so he took readers through the facts, as best as we can know them through the written record. It wasn’t a brief interview. We had to run it over three weeks. Our honour to do so, of course.

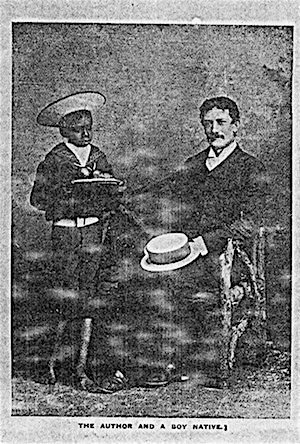

Left: One of the images used for the interview, from Willshire’s publication on “the Australian Stone Age”, titled The Land of the Dawning. It shows “the author and a boy native”.

Mr Kimber’s contributions did not always deal with events of early contact history. In 2007, the year of the Intervention – a time of great tension and upheaval in Alice Springs, in particular for the residents of the town camps – he had invaluable information and perspectives to offer on the many different paths over recent decades that had brought non-Arrernte people into town as well as the steps taken in the mid-1970s to formalise arrangements for the living areas that became known as the town camps. He could relate this history through direct personal contact with people, having volunteered to go in the company of Wenten Rubuntja to conduct a survey of fringe camp dwellers around the town.

In the hands of these two men the survey was much more than a counting exercise. They sat down with people, heard their stories, heard from Arrernte people about who was welcome to stay and why, what kind of connections to Arrernte country they recognised. All of this Mr Kimber recalled – 30 years later – in a long interview with me which we ran over two weeks, putting names and personal context to the often arid and ill-informed debates of the time.

These stories of migration – some of them, of forced migration – were the substance behind his rejection of the term ‘urban drift’, with its implied passivity. The migration was either out of the hands of the Aboriginal people concerned or was motivated by “a sensible decision in their mind to come here, for whatever reason” – and Mr Kimber had given the examples.

Another significant contribution he made in the News was a five-part series, published in 2005, on drought, to which he gave the poetic title, ‘The heavens have turned to bone’, a translation of a Diari expression. The first part gave a gripping account of the experience by desert Aborigines of an extreme drought, likely to have occurred in the 1770s, and thankfully not since. In a town where history before the arrival of Europeans can be casually dispensed with in a paragraph, this was eye-opening material.

Another significant contribution he made in the News was a five-part series, published in 2005, on drought, to which he gave the poetic title, ‘The heavens have turned to bone’, a translation of a Diari expression. The first part gave a gripping account of the experience by desert Aborigines of an extreme drought, likely to have occurred in the 1770s, and thankfully not since. In a town where history before the arrival of Europeans can be casually dispensed with in a paragraph, this was eye-opening material.

Right: In May 2005 Alice had been experiencing a prolonged dry spell. This photo used to illustrate Mr Kimber’s drought series shows one of dozens of perished kangaroos at Wigley’s Waterhole just north of the town.

Here are a few lines from Part 3 , his evocative account of a drought breaking. We are in 1866, and it hasn’t rained for three years:

“Young children were shown how to choose nice, smooth stones to hold in their mouths, as with the adults, to cause them to salivate and ease the pangs of thirst, though mingulpa native tobacco was preferred. … The rounded stones were invariably water-tumbled white, grey or green, the colours of clouds and hail, and water and water-moss.

“The old people were the first to notice the slight change in their perspiration, the faintest scent from some of the trees, a shininess on some of the leaves as they too ‘perspired’, and the increasing activities of ants. Cloud build-up came, but still there was no rain.”

He goes on with some detail about the preparations people made, then came the downpour “in a waterfall of red-mud rain, clearing the dust-storm in an hour”:

“With the first heavy rain-drops those few people who had not already discarded them had taken their smooth stones from their mouths. Some had joyously thrown them outside, into the dust-clearing rain, others placed them on the inside edges of the shelters.

“Well over a century later, when a bushfire has swept an old camping area clear, or the grazing and trampling of cattle have caused the soil to erode, some of these smooth stones can still be seen. They strike the eye because they are out of context in the general landscape.”

This is memorable writing. Such vivid, sensual detail of Aboriginal people living in this country as they did before the arrival of Europeans and then the deft jump forward to now, showing how the traces of that life that can still be seen if you care to look.

But what kind of difference has all of this – exceptionally interesting, revealing material put into the public domain for broad consumption – what kind of difference has it made?

When I look back over the decades I have spent in Alice Springs, I can see that there has definitely been change. The old settler ways and the old romantic image of the hardy Outback town, blind to its whiteness, have come critically under pressure from contemporary Aboriginal ways – Aboriginal political voice and strength as well as all those things that get summed up as ‘Indigenous disadvantage’.

This shift often seems like a matter of one step forwards and two backwards, but that it has not caused a much greater sense of fracturing, can be put down in part, maybe even to large degree, to the cultural work done by many people, Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal, in the fertile space between us. I’m thinking of the art and music and other creative projects and partnerships, the language learning and maintenance, the intellectual enquiry made broadly accessible through film, journalism and other writing, and the inter-cultural relationships that have been built around all of this, on a ground of generosity and forgiveness, compassion, and a mutual desire for a better future.

In this Mr Kimber has undoubtedly made a major and unique contribution. The town and region have much to thank him for.

Links to the ALICE SPRINGS NEWS articles mentioned above:

Coniston series Part 1, published on 10 September 2003, is archived here. The links to each article in the series are assembled here. This series is in our foundation archive of the printed newspaper. Each page archives all the major articles for the issue. Scroll down the page to get to Mr Kimber’s Coniston article.

Willshire series Part 1, published on 20 November 2008, is archived here.

Town camp history, published on 21 June and 19 July 2007, is archived here and here.

Drought series Part 1, published on 18 May 2005, is archived here.

Last updated 27 May 2021, 10.17am.

“Mr Kimber” is a formal title rarely used to describe the gentlest, kindest,loveliest old ratbag bloke in Alice. A scholar and a gentleman – The Galloping Glacier who kicked 10 goals 4 points at full forward in a breakout performance for bottom team Melanka against top team Pioneers in the early ’70s in a game of footy at Traeger that will live forever in Central Australian folklore.

Dicky Kimber – Legend. That about sums it up, I reckon.

Dick and Iain, two powerful figures in our community: great, humble,friendly who made me welcome at work at Alice High in the ’70s, will be forever in my memories.

The booklet by Dick,”Cultural values associated with Alice Springs water”, was part of my toolkit when working in the tourism industry.

This wonderful tribute to an extraordinary man required the touch of a rare journalist – one with deep knowledge, and empathy. We are very fortunate to have both of you.

You knew him for his scholarly abilities, we who were at Melanka Hostel with Dick just knew him as a bloody good mate. What a wonderful story I have just read. Hey Dick, go you good thing.

DILLON (Bloody Brian) O’Sullivan

Great tribute Kieran. I have a few letters from Dick, who generously assisted my research into Coniston and a biography of his friend Darby Ross.

I was pretty young at the time and Dick was so enthusiastic about my project and I credit him with inspiring me to find a way through it all and complete it.

He also inspired me to delve deeper into NT history and try to understand the context within which many of Darby’s stories were told and the way Aboriginal oral history and written history could sit together to tell a story.

He reminded me so much of Darby – generous, inquisitive, trying to see both sides, fascinated by the clash of cultures and finding humour in it, the importance of remembering the past and trying to understand it, and of course a love of footy!

Loved seeing this story about my wonderful friend, Dick.

I also have a trove of Kimber letters, dating back decades, as Dick kept me updated about those stories of Central Australia that I was missing in the States.

I’m only sorry that I couldn’t be there to toast him myself. Thanks to Kieran for the tribute.

I was so fortunate to have Dick as a teacher, and proud that I was able to cite him in my Masters thesis.

Dick Kimber is a wonderfully generous man.

Sorry I couldn’t be there to honour you, Dick, but I’m toasting you now.

Thanks for all the yarns and all the stimulation. These are fitting tributes.

Dick taught my wife, Bess Nungarrayi, at Alice Springs High School in the early ’70s. Bess remembers him as a fine and inspiring teacher. He was a good friend to my father in law, Dinny Japaljarri. He was one of the kardiya that Japaljarri most trusted and respected. Dick has given me his time and knowledge generously and without hesitation. He is one of those rare human beings who treats the subjects of his research and scholarship as complete and complex, fully human personalities regardless of their culture and ethnicity. He is above all an insightful student of our shared humanity.

I have also had the great good fortune to serve on a jury with Dick’s wife Margaret. I have always acknowledged and recognised our need for the support that is given us by our loving spouses/partners. Margaret gave me the advice and support I needed to take on the daunting task of a jury foreman in a complex and difficult case. They are a wonderful couple and both a great asset to this town, the Territory and the country.

Thank you both,

Cheers,

Dave Price

Wonderful tributes to a remarkable and humble scholar and gentleman. There would be few published or unpublished works ranging across Central Australian art, ethnography, history and environment which were not enriched by Dick Kimber. A local and national treasure.

Mr Kimber was my 1st-year English teacher at Alice Springs Highschool. Didn’t learn a lot of English but learnt a lot of things and was exposed to ideas that were needed in the Territory at that time, these have been invaluable all my life.

Always wanted to thank Dick and saw this chance.

Thanks, Mr Kimber.

Hi Dick. It’s Elizabeth McDonald. I have meet you in Alice Springs. You gave me a photo of my great grandfather Sandy the old white Scottish man who owned the old pub at Arltunga.

I would like to know if readers can send me some photos because we are having a big family reunion in Buruga this year. Please give me a call on 0499 724062.

Such a wonderful summary of Dick’s impact on our community. Thanks, Kieran, you continue to shine. Vale, Dick Kimber.

A great mate and friend.

Dick could always see all points of view.

Terry’s movie pal and choc top lover.

Marg, Barb and Steve, you did him proud.

Love Gadsby family.