Grandson and grandmother come before the Royal Commission

16 March 2017

Above: BY with a legal representative and Counsel Assisting Tony McAvoy SC during a video link to the commission.

By KIERAN FINNANE

“Where are their parents?” It’s a frequently heard question in the popular debate around young people in trouble and in detention.

Today the Royal Commission into youth detention in the NT heard from a grandmother. She followed her grandson into the stand.

His evidence was actually via video link but was webcast live into the commission and streamed on the net. His father was present as his support person. He went by the pseudonym BY, and to protect his identity his grandmother was named only as CA, although she is a well-recognised figure around Alice Springs.

His oral evidence, in response to questioning by Counsel Assisting the Commission, Tony McAvoy SC, focussed mainly on what happened to him while in detention, but his statement was quite frank about the kind of trouble that had landed him there.

It began when he was around 13, stopped going to school and started drinking (introduced to it by an adult, his father’s cousin). The first offence for which he was sentenced was not specified, but he was put on diversion. A breach of its conditions led to his first stint in detention, at Aranda House, then sent to Don Dale.

When he returned to Alice Springs, boredom led to him hanging around the streets with mates – “a dangerous place particularly at night”.

“I had seen people beaten up. I took a knife from home because I was worried someone might stab me for something as simple as not giving someone a cigarette. I got caught carrying a knife.”

Back to detention, three months to serve in Alice Springs. Got out, “same old stuff”, got caught, sentenced, back to Don Dale, back to Alice, back to Don Dale again, and into the adult gaol in Darwin while he was still 17.

Again his statement is quite frank about his behaviour. He was no model prisoner, but neither was he in a model prison. For instance, although he had not been spitting – according to his statement and repeated today in his sworn oral evidence – he was subjected to wearing a spit hood, without notification or explanation. He even says a guard apologised for putting it on, as “I know you haven’t been spitting”. The hood was put on each time he went for medical attention during a five day period when he was otherwise kept in isolation and lockdown, allowed out only twice for showers.

I could go on at the risk of enticing more comments from those who are convinced “the little darlings” get what they deserve. (That’s working out so well for everybody, isn’t it?)

So my interest is more in what BY’s grandmother had to say about what could make a difference in the detention system in her view. She spoke as a grandmother but also as someone with extensive experience in the community sector.

So my interest is more in what BY’s grandmother had to say about what could make a difference in the detention system in her view. She spoke as a grandmother but also as someone with extensive experience in the community sector.

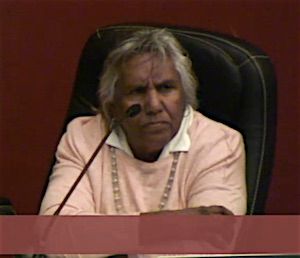

CA (left) is trained in suicide prevention (Applied Suicide Intervention Skills Training, ASIST). She has organised groups with mothers who have lost their children to suicide. She is a family wellbeing trainer, has worked in child protection, around narrative therapy and in groups for women who have been sexually abused. She has been a representative on the NT Women’s Advisory Council and represented NT women at an international women’s conference in Beijing. She worked as a counsellor for the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse.

One of the problems CA thinks the detention system faces is “not looking at Aboriginal kids as individuals”. They are instead all put in the “one box”. Because her grandson is Aboriginal it is “assumed he came from a broken home, a dysfunctional home”. That is not the case: she described a “close family”; both his parents are “workers, home buyers”. She credited them also with passing on the inter-generational learning that she had received from her parents and grandparents: “We kept our values and beliefs.”

So she would like to see the system take each case individually: talk to parents, get them and the grandparents involved. “Support for that child comes from the parents, grandparents and the community.”

She told the commission of the difficulty she had in getting information from police about what was happening when her grandson was first arrested at just 13 years of age. It was a “scary moment”, as the family had no idea of what was involved, what to expect.

BY’s mother, who is non-Indigenous, had more luck getting answers; the attitude changed when she, CA, went in to police station.

CA spoke of hand-picking people to form an “Aboriginal support team” to work with young people in the system.

She was aware of the limits of relying on Elders to do this work, as “only a handful” are active and they are also required for other programs.

There are younger men and women who have the requisite “empathy” for the job, but they need better training: “Sometimes they need to broaden their minds” as she did when she undertook the learning that allowed her to work as she has done.

They also need to be trained to stand up to authority figures: “A lot of our people are ‘yes’ people, they don’t speak up for the children and themselves.”

They also need to understand that “we work with mandatory reporting”: they must not let things be “swept under the carpet”.

“If it’s a family member in the community, they might let it go and it’s wrong,” she said.

Of processes in the system that could be improved, she suggested the following:

• Make sure assessment is done at entry and exit.

BY had a medical check although never an eye test until recently, when he was given glasses; and never a hearing test, although it is known there is a high incidence of deafness amongst the Aboriginal prison population.

• Look at educational level.

Unhappiness and difficulty at school was one of the reasons BY started to go off the rails, it would seem.

Schooling in the detention centre came down to working through booklets, he said. He didn’t learn much, the work was easy and in any case the answers were at the back – he used to cheat a lot.

He enjoyed learning about cooking at Don Dale but a transfer back to Alice prevented him from finishing the course.

He was later “kicked out” of the classroom and put on a work program, mowing lawns and other odd jobs around the centre.

• Goal setting for the youth.

BY said of himself that he “spent a lot of time thinking about my problems but I didn’t come up with any real answers.”

His statement refers to one guard, Travis, who knew his family: “Sometimes we’d talk about my life and what I would do in the future.”

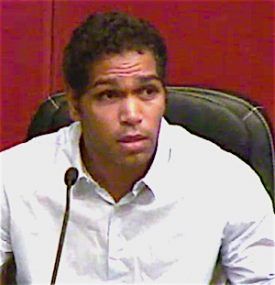

Jamal Turner (left), who appeared before the commission on Monday, said in his statement that apart from one time with the program called Reconnect, “I don’t remember anyone else ever helping me plan for my release or helping me once I was released. My mum was the only one.” This was despite his serious recidivism: he was in detention over 10 times between the ages of 14 and 18, his offending rooted in his Ice addiction.

Jamal Turner (left), who appeared before the commission on Monday, said in his statement that apart from one time with the program called Reconnect, “I don’t remember anyone else ever helping me plan for my release or helping me once I was released. My mum was the only one.” This was despite his serious recidivism: he was in detention over 10 times between the ages of 14 and 18, his offending rooted in his Ice addiction.

His concluding thoughts on the system are both unsurprising and damning. He read them aloud to the commission on Monday:

“I don’t think the detention system makes kids better. The whole time I was in detention I was worried about being assaulted by guards or other kids. That’s why I mostly kept to myself. I also acted tough because if you don’t then people would pick on you. I think most of us that come out of detention come out more angry and acting tough than when we went in. It didn’t make me want to be a better person.”

• Have a mental health team.

The commission heard yesterday from shot supervisor at Don Dale, Barrie Clee, how ill prepared staff in the system were for dealing with those issues: not only no training, but no information about the the specific problems or disability of their clients.

Despite some very challenging physical experiences, BY said his worst memories of detention were when he felt “anxious, lonely, and scared”. Visits from his family would help but there were long periods, when he was in Darwin, when those were infrequent and he felt “really alone and worried about what would happen to me.”

“Where are the parents?”, always an interesting question when you put it in an historical context.

How many of our good old pioneering families recognise their not completely white offspring. You know the children of those women and young girls used by these fellas. Who owns the stations and businesses started by these guys on country stolen from the children’s Aboriginal family. And often built with cheap or slave labour. The white kids or their black brothers and sisters?

Our present situation is built on our past history and as much as we want to hide it, it’s still there and it’s not pretty. With all the talk about domestic violence today we need to remember that this place was settled by white people with a huge amount of violence. The effects of which are still impacting today. That violence and mistreatment was accepted as the norm and ok to a great extent, and I think that many in the community still think it’s ok.

It’s wearying having to always remember to not only lock the door when I leave the house, but to also lock it when I re-enter the house.

Following a lapse on the second count (how could I forget?) last night I awoke to find a midnight creeper helping himself to the beer in my fridge.

On his way in, he had armed himself with a pair of secateurs. Held aloft in a threatening manner, they make for a scary sight.

Now, I don’t know if he comes from a broken family, or from a loving family. But I do know that should he ever find himself in detention, then I will definitely be among those reckoning he is getting what he deserves.

During this Royal Commission we hear a great deal about the alleged mistreatment of detainees.

We are hearing much less about the mistreatment doled out by those same detainees to members of the general public.