Namatjira project: a film and a legacy

20 October 2016

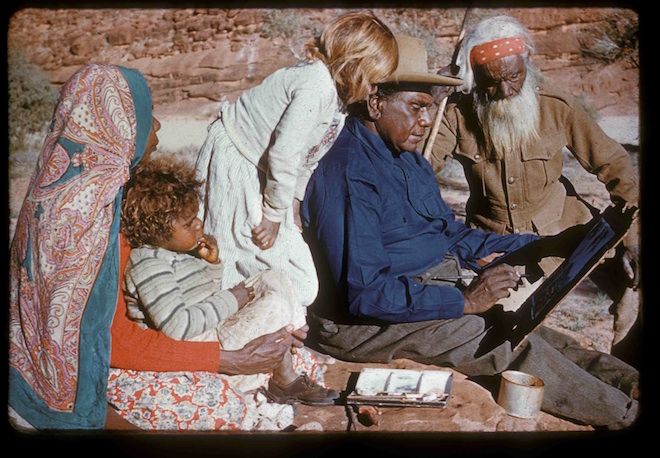

Above: Albert Namatjira with his wife Rubena, some grandchildren and father Jonathon. Gross Collection, courtesy Strehlow Research Centre.

By KIERAN FINNANE

Namatjira is probably one of the most recognised names in Australian art history as well as in the story of black-white relations in this country. It was the audience reaction to this name in an earlier theatre production, Ngapartji Ngapartji, that turned the attention of Big hART, the art for social change company, to their second project in Central Australia, simply named the Namatjira Project.

Starting in 2010, now six years later it has reached an ending of sorts. As with all its projects, Big hART aims to leave a legacy on which the community it works with can build. Part of the legacy in this case is a documentary, tracing the project’s journey, and at the same time the lives of the Namatjira family, descendants of the illustrious artist Albert Namatjira. It will be shown this Friday at Ntaria (Hermannsburg), Albert’s home for much if his life.

There in 1934 he met the non-Indigenous watercolour painter Rex Battarbee. Their wonderfully fruitful friendship was the central theme of the theatre production developed in the course of the project – Namatjira starring Trevor Jamieson – seen by some 50,000 people in the course of its national and UK tour.

The friendship will also feature in the documentary, but attention is equally turned to the lives of Albert’s descendants, the “development of their inter-cultural art” and their “struggle to gain recognition and support”, as Big hART director Scott Rankin puts it.

The profile of this hard-working group of artists has been reinvigorated in recent years – their participation in the recent Parrtjima Festival in Light is but one example. However, Rankin questions the level of support they and the broader remote community art movement receive, given the importance of art and culture to their well-being as well as to the image of the nation, which “trades off Indigenous art”.

“Compare it to the kind of resources poured into the dysfunctional car industry,” he says.

A particular injustice, which receives some attention in the film, is the issue around copyright to Albert Namatjira’s works. The artist himself apparently signed away seven-eighths of his interest to Legend Press, owned by John Brackenreg. In 1983 Legend Press bought the residual rights from the Public Trustee, manager of Albert’s estate, and owns them to this day. (See our recent story and comments here.)

A particular injustice, which receives some attention in the film, is the issue around copyright to Albert Namatjira’s works. The artist himself apparently signed away seven-eighths of his interest to Legend Press, owned by John Brackenreg. In 1983 Legend Press bought the residual rights from the Public Trustee, manager of Albert’s estate, and owns them to this day. (See our recent story and comments here.)

Right: Gloria Pannka made the copyright injustice the subject of her entry in the inaugural Vincent Lingairi Art Prize.

With the national rollout of the film Big hART will launch the Namatjira Legacy Trust, one of the aims of which will be to raise the funds to buy back Albert’s copyright for his family.

Rankin says that this is now more a moral than financial issue: “The healing that would come from the return of the copyright would be of much higher value than the royalties. It’s about what is right and the ongoing cultural relationships in this country.”

All are welcome at the screening, from 5:30pm this Friday, 21 October, at the Hermannsburg Heritage Precinct, Ntaria. There will be a free BBQ, songs from the Hermannsburg choir, short films from the Namatjira project and a post screening Q&A. Bring a blanket to sit on.

Note: This article was modified on 21 October with respect to the timing of the launch of the Namatjira Legacy Trust (during the national rollout, not at tonight’s premiere).

RELATED READING:

Namatjira: for the man and now the project, art was a catalyst for change

Colours of landscape, of dreams across five generations