Before and after that famous handful of sand

14 October 2016

By KIERAN FINNANE

By KIERAN FINNANE

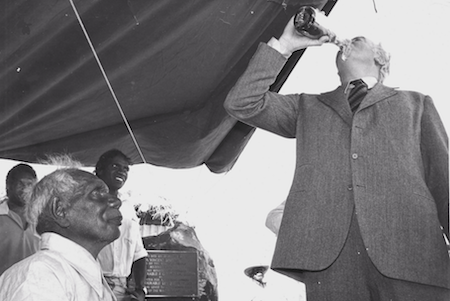

For most people knowledge of the Wave Hill Walk Off and what flowed from it consists of a photograph and a song. Mervyn Bishop took the 1975 photograph showing Prime Minister Gough Whitlam pouring into the hand of Vincent Lingiari – stockman and Gurindji elder – a little of the red sand of his country. Paul Kelly and Kev Carmody wrote the song,“From Little Things Big Things Grow”, in1991; it has become the folklore of the Whitlam gesture.

Together song and photo are taken to celebrate a moment in Australian history when there was some attempt to put things right – the start of restoring land rights to Aboriginal people.

Not quite so, discovered historian and author Charlie Ward when he set about expanding his knowledge of what actually happened then, in the lead-up and subsequently.

Lingiari received the sand in his right hand. In his left hand he is holding a document that we assume to be title deeds under Australian law to the land the Gurindji owned under traditional law. The Wikipedia entry on “From Little Things Big Things Grow” says, for instance, “In 1975, 3,236 km² of land was handed back to the Gurindji people.”

In fact, what they received at that time wasn’t the award of Aboriginal freehold title, as allowed for following successful claim under the Commonwealth’s Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976. Rather it was a pastoral lease. They did not gain Aboriginal freehold title until 11 years later.

“The soufflé’s sinking quite quickly once you’ve realised that,” says Ward.

His book, A Handful of Sand, published by Monash University Publishing after eight years of exhaustive research, recasts the moment not as the start of something, but as coming in the middle of a process of enormous social change. Despite the determined efforts of the Gurindji, especially the leaders of that generation, the push and pull of all kinds of contradictory forces ultimately undermined both their aspirations and those of all Australians who aligned themselves with the symbolism of Whitlam’s gesture.

Lingiari and his fellow stockmen followed their fathers and grandfathers into the pastoral industry. They loved working with cattle and were essential to the operations on Vestey’s Wave Hill Station. “Born in the cattle / grow up in the saddle”, as Ted Egan put it in the song he wrote about Lingiari after the old man’s death, which he part recited, part sang during the moving Alice Springs launch of Ward’s book.

What they didn’t love was working as semi-indentured labour, for decades, ‘paid’ in rations, no wages. Grown men, even elders were ‘boys’ in the stock camp; the women, ‘kitchen girls’ and ‘house-gins’. These were the “poor bugger me” of Egan’s other song, “The Gurindji Blues”, to which the launch audience was treated.

What they didn’t love was working as semi-indentured labour, for decades, ‘paid’ in rations, no wages. Grown men, even elders were ‘boys’ in the stock camp; the women, ‘kitchen girls’ and ‘house-gins’. These were the “poor bugger me” of Egan’s other song, “The Gurindji Blues”, to which the launch audience was treated.

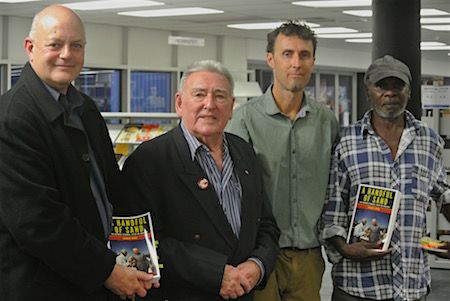

Left: At the Alice Springs launch, from left, Russell Goldflam (MC ), Ted Egan, Charlie Ward and, representing the Gurindji, Milton Splinter.

For Ward, it captures the story more closely than the later Kelly/Carmody ballad. Egan wrote it in 1969 and recorded it in 1971 with Galarrwuy Yunupingu and a spoken introduction by Lingiari. The single went on to sell some 20,000 copies, with the proceeds helping fund the Aboriginal Tent Embassy which sprang up in Canberra the following year.

Although the song expresses the defiance and the clear-sighted determination of the struggle at that time, the final lines spoken by Lingiari now have the quality of epitaph: “Oh ngaiyu luyurr ngura-u / Sorry my country, Gurindji”.

From 1953 the men were paid unequal wages – $6.34 a week compared to a white stockman’s $33 – and by the end of the decade the ‘headboys’ and their families had been given tin sheds to live in. Until then they had been camping in the open, with wurlies as their only shelter.

A vision of a better life had been articulated by one of their elders, Tipujurn (Sandy Moray) from about 1950: getting back their own land and running their own cattle operation. It gradually gained acceptance – “a dream they would cling to, until the time was right”.

That time came in 1966. The Commonwealth’s Arbitration Commission decided that all pastoral workers in the NT should be paid equal wages but that the transition be made over three years to allow pastoralists time to adjust. The Gurindji were sick and tired of waiting: anger over unequal pay boiled over and on August 23 they went on strike, walking off Wave Hill Station.

They went first to the Wave Hill Welfare Settlement (Kalkaringi) and then on to Daguragu on Wattie Creek, the site of the famous ‘handover’, and from where they would strive to create a new living area for their people, in charge of their own lives, sustained by their own cattle operation under the name Muramulla. Their aspirations included a fully bilingual school, where Gurindji children would be equipped for independence in the contemporary world, but also educated in their traditional law and culture.

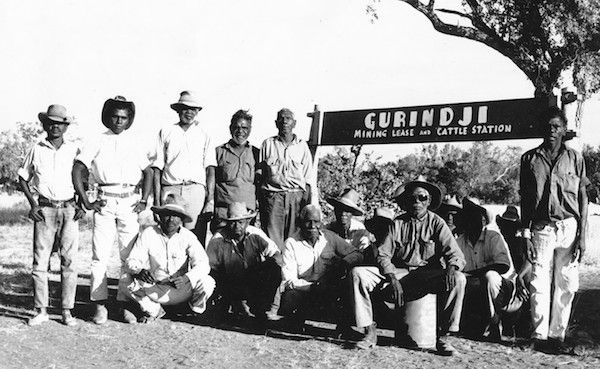

Above: Gurindji men with the sign painted for them by Frank Hardy, at Wattie Creek in 1967. Vincent Lingiari is standing next to the sign at left. Brian Manning Collection.

Ward’s book details this struggle. In many ways it was visionary and valorous but, sadly, in the fundamental respect of achieving genuine lasting independence, it foundered.

Folklore would have us believe that Vestey’s, the British company that owned Wave Hill Station, was the villain in the saga, but for Ward conservative politicians, nationally and in the Territory, were the Gurindji’s real foes.

Peter Nixon, Country Party Minister for the Interior in the federal Coalition Government, wanted at all costs to avoid dealing with the issue of land rights. After a visit to the Gurindji at Wattie Creek in 1970, he told the House of Representatives : “The government believes it is wholly wrong to encourage Aborigines to think that because their ancestors have had a long association with a particular piece of land, Aborigines of the present day have a right to demand ownership of it.”

A window of opportunity opened for the Gurindji when Whitlam led Labor to power in the following year. The Gurindji strikers had been embraced by the Left, in particular by the student and union movements, and they had a persuasive ally in the writer Frank Hardy, who in 1968 published his book about their struggle, The Unlucky Australians.

The Gurindji took full advantage of these relationships. Kelly and Carmody’s song suggests that “eight years went by, eight long years of waiting”, but far from it, says Ward: “They weren’t sitting around, they weren’t waiting, they were working really bloody hard for that eight years.

“They were accumulating cattle, building cattle yards, building their homes at Wattie Creek with the help of Abschol and other groups. And many of those senior Gurindji people were travelling interstate, raising awareness on speaking tours in Sydney, Melbourne and Canberra, meeting with people like Bob Hawke, then leader of the ACTU.

“In between all that, they would be sitting in the camp making boomerangs and other artefacts, which they’d give to kartiya (their non-indigenous friends) to take with them down south to auction, to raise money for the business, the Muramulla Cattle Company.

“There was lobbying, petitions, letter-writing, meetings with Ministers. All this went on for that eight years, a big struggle for land rights.”

“There was lobbying, petitions, letter-writing, meetings with Ministers. All this went on for that eight years, a big struggle for land rights.”

Right: The moment after the ‘handful of sand’, PM Whitlam taking a slug of champagne, Vincent Lingiari and his son Victor Vincent looking on. Photo courtesy Rob Wesley-Smith.

The Gurindji’s claim under the Land Rights Act was not submitted until four years after the ‘handover’, largely as a result of the fledgling and conservative NT Government threatening them with eviction. This was on the basis that they hadn’t met certain conditions of the lease, such as building the requisite amount of fencing for that financial year.

The threat of eviction was unprecedented in the history of the pastoral industry, says Ward. Some two thirds of leases were usually in breach of their covenants.

“It was about making a point. It was the early days of self-government and the Country Liberal Party and Chief Minister Paul Everingham were adverse to Aboriginal land rights and Aboriginal-owned cattle stations.”

Other barriers stood in the way of Muramulla’s success, including meeting the requirements of the Department of Aboriginal Affairs (DAA) and the Aboriginal Development Commission who funded them. Then came a blow from which it would have been hard to recover in any circumstance: they were forced to de-stock under the national Brucellosis and Tuberculosis Eradication Campaign.

By the time they won freehold title under the Land Rights Act in 1986 the decline of the cattle operation was terminal.

They were back on their country, however. That was something, but they had to contend with other powerful drivers of social and technological change: “The conditions in which ceremonial life could take place were changing, it was becoming more and more challenging to maintain it,” says Ward.

“The economic relationships within the community were changing, young people had different priorities and greater independence, some were leaving, old people were dying.

“There were responsibilities that were inherited with self-management that weren’t necessarily chosen, huge pressure on senior people to maintain law and order and to manage all these organisations that were created under self-management and self-determination policies.

“It was onerous and ongoing, making daily demands on their time and energy and taking it away from maintaining traditional law and culture.”

“It was onerous and ongoing, making daily demands on their time and energy and taking it away from maintaining traditional law and culture.”

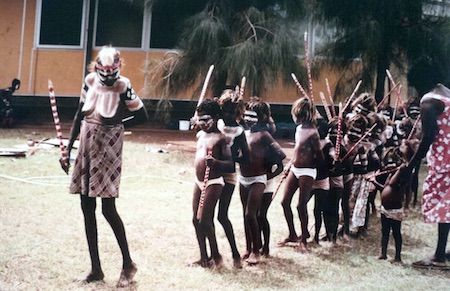

Left: A girls ‘Culture Class’ at Kalkaringi School, 1983. Photo courtesy Elaine Bullock.

They were also often caught between external agencies working at cross purposes. Ward points out that Aboriginal self-determination was the policy of DAA, but that was only one agency providing services in Kalkaringi and Daguragu. The Department of Education, for example, resisted the Gurindji elders’ desire for a genuine two-way school.

“The Gurindji had a vision about where the school should be – in Daguragu – and their own involvement with it,” says Ward. “There would be whitefella teachers, but the elders would also teach culture and law, it had been clearly articulated over a 15 year period.”

What they got instead was a school in Kalkaringi, delivering a largely mainstream program, with the elders allocated just one lesson a week for language and culture. Their vision was never realised.

“They gave up and passed away,” says Ward. “It’s still a sore point in the community, that the services are in Kalkaringi and that Daguragu is neglected and run down.”

There was some success, in that Gurindji of the next generation were able to step into roles within the school, the clinic, the council and so on, but not managerial roles – much as has happened in other remote communities.

And what of the non-Aboriginal side of the story? It’s something Ward has thought a lot about.

“I’ve interviewed dozens of former public servants and community advisers and in almost all cases I’ve come away with a sense of people with good motivations doing their best in difficult circumstances. So I don’t ascribe blame to individuals.”

Ward hopes that readers will get an understanding from his book of the pressures and the massive contradictions that Indigenous people were trying to resolve in that period, of the burdens placed upon them by virtue of their situation and external forces.

He thinks too much importance can be ascribed to policies in place at the time, and that this is often the case when we look at what’s happening in Aboriginal communities.

“I don’t think we do that to the same extent when we’re looking at social developments in the mainstream. A large part of what was going on at that time was more a result of the dynamics of inter-cultural change and where that process was up to at that time.

“The economic dimension also had a big influence and was an outcome of policy quite often, but possibly the policy of five years earlier, or more universal policies and not the policy of self-determination.

“I’m not saying policy is irrelevant – the effect of the electoral cycle and funding cycles is quite significant, but there was a lot else going on. The Gurindji leadership were renegotiating the place of traditional law, they were dealing with restrictions on the way of doing things imposed by the mainstream. That was taking a lot of energy and time and creating a lot of conflict and change within the society and alcohol amplified it all.

“Another thing in that period was that politicians were realising the parameters of self-management. They were in a double bind. How hands-off could they be if an Aboriginal community ran out of food, or if people were really struggling without basic services because of their lack of experience in running a business or managing a utility?

“Responsibility gets slated home to government, so they had an interest in intervening and employing people who would prevent these things from happening.”

Ward’s account stops in the mid-80s and he is reluctant to comment on present-day circumstances, even if he wants readers to draw out the story’s contemporary relevance for themselves, in particular to use hindsight to invigorate more discussion about the role of government in remote communities, whether it’s fit for purpose, whether there are ways it could be modified, and approaches changed.

He writes in his preface about growing up with a romantic sense of the Australian bush inherited from his father (historian Russel Ward) and the folk songs he sang. They celebrated bushrangers, shearers, drovers, alcoholics and stockmen but Aboriginal people were absent. He hopes his book gives readers a sense of Gurindji society and the land rights movement as driven by real people, that “brings them into the world in a way we can relate to, to understand their struggles, their humanity, the issues they had to deal with”.

Note: All historic photos are reproduced from A Handful of Sand.

Yet another delightful presentation, Kieran. Thanks.

Well done, Kieran. A comprehensive review of an excellent book, a must for anybody who wishes to come to terms with complicated First Australian issues. Charlie Ward’s book is as significant a literary milestone as his father’s The Australian Legend – and that’s a big call!

Aboriginal groups like the Gurindji can’t effect rehabilitation on their own, but they seem to be doomed to levels of support from kartiya that are often self-centred and counter-productive. The one single positive outcome is that the Gurindji are still in contact with their land, unlike so many other groups, who were dumped as fringe dwellers around Alice Springs, Katherine and Tennant Creek. Hopefully, they will eventually forge a lifestyle for their members, based on the old and wonderful vision of those great Australians, Vincent Lingiari and his team.

I agree Phil, thankyou Kieran. Let’s address the education story. Federal and Territory agendas.Time for some truths. We need to hold those who have been in power accountable.

I recently spoke with Philip Ruddock, asked him about his Five Point Plan – definitely linked to national education management. Asked him if he felt it was linked to the suicide epidemic – he gave me his new card. The Hon Philip Ruddock. Special Envoy for Human Rights. 2018-2020 as candidate for the United Nations Human Rights Council. He invited me to come and see him.

Maybe he could be interviewed and with many others held accountable.

@Diane de Vere, ‘Holding people accountable’? Diane, I suggest you reread Kieran’s review. One strength of Charlie’s book is its argument that it is hard to blame individuals for the outcomes of complex processes. Historical understanding such as he offers is an antidote, not a prop, to the desire to know that one is on the right side of history.

Thanks Tim. It is not the Individual but the System he [Ruddock] represents, the political machine. And yes they must be held accountable and he would be a good one to start with, The father of the House.

My personal comment was a response to the education thread in Kieran’s review. How the stockmen’s “aspirations included a fully bilingual school, where Gurindji children would be equipped for independence in the contemporary world, but also educated in their traditional law and culture.”

“Ward points out that Aboriginal self-determination was the policy of DAA, but that was only one agency providing services in Kalkaringi and Daguragu. The Department of Education, for example, resisted the Gurindji elders’ desire for a genuine two-way school.”

“The Gurindji had a vision about where the school should be – in Daguragu – and their own involvement with it,” says Ward. “There would be whitefella teachers, but the elders would also teach culture and law, it had been clearly articulated over a 15 year period.”

“What they got instead was a school in Kalkaringi, delivering a largely mainstream program, with the elders allocated just one lesson a week for language and culture. Their vision was never realised.”

This pattern has been repeated over and over.

“Ward’s account stops in the mid-80s and he is reluctant to comment on present-day circumstances, even if he wants readers to draw out the story’s contemporary relevance for themselves, in particular to use hindsight to invigorate more discussion about the role of government in remote communities, whether it’s fit for purpose, whether there are ways it could be modified, and approaches changed.”

Tim believe me I know of this struggle and as an educator who has worked with the traditional elders of the central western desert who shared this same vision, [I refer to the Pintupi Kintore 1980’s] I now bear witness to the devastating impact on the children and families of these wise visionary leaders.

Herron, Howard, Ruddock, Shane Stone to name a few set the agenda and orchestrated the plan, announcing self determination and self management did not work. Thirty years of reforms, restructuring, secret behind closed door agreements, disenfranchise and divide communities and fail to deliver services.– while politically selected highly paid Government ministers and senior executives are shuffled around never being held to account.

Am looking forward to reading Charlie Ward’s book.

Commonwealth was, still is, protecting its abusive claim it is lawful to divide and qualify Australians’ rights and responsibilities using racial identification as their measure.

Since arrival of Captain Philip, from management to self governing, then throughout independence under the Australian Constitution, clear intent has been that ALL Australians to be equal in their rights and responsibilities regardless of racial identification.

Yet the Commonwealth qualified, still qualifies, worthiness of Australians using racial measures.

The Commonwealth claimed pre 1967 it lacked constitutional authority, yet still qualified rights and responsibilities of Australians, and NT residents, using racial identification as their measure, with most abused their label “Aborigine”.

Terms “Aborigine” and “Indigenous” remain racist terms.

Terms are used by racists and governments, to confuse, deny, delay, distract and to divert people, particularly those simple or ignorant, away from learning, then exercising and protecting their otherwise held rights as Australians.

The Commonwealth qualifies rights and responsibilities of Australians using racial tags … likely soon to seek an endorsement for its racism.