Learning from the hunter-gatherers

31 December 2014

By PETER LATZ

By PETER LATZ

Given both my background and my botanical training, it is no wonder that I decided to set about documenting traditional Aboriginal use of plants. It’s true that I knew all about the plants I had come across during my youth at Hermannsburg, but that was mostly just kids’ stuff, and there was still a hell of a lot more about this subject that I had to learn. Being a Government Botanist there was no way that my bosses would allow me to conduct my research during my working hours. After all I was being paid with taxpayer’s money, and it couldn’t be wasted on blackfellow stuff. Also at that time I was busy helping raise a family, so my spare time was limited.

Luckily, during 1974 Doctor James O’Connell turned up, and helping him in his endeavours enabled me to sneak in some ethno-botanical research. Jim was a ‘goddamm Yank’, but he was a smart one, clever enough to be employed by the ANU Prehistory department in Canberra. When I made his acquaintance, he was living with the Anmatjera people at MacDonald Downs Station, researching their hunter-gatherer practices. It was great to get out bush with Jim’s main informant Jacob, and learn all about this bushman’s plant skills. Going out with the women was even better, as they knew more about plants than the men.

Jim encouraged Jacob and his mates to make him a traditional kangaroo-skin waterbag. This was a unique object, one which I had never seen before and in fact before that time, didn’t even know existed. Making this waterbag requires a great deal of skill. The first thing you have to do is kill the kangaroo by hitting it on the head with a boomerang, so as not to pierce the skin. Then you have to skin the animal through its neck cavity, once again making sure you don’t cut a hole in the skin. Tying off the four holes left by removal of the hands and feet, you now have a water-holding container that can be filled and emptied by the hole in the neck region. About a week before this event you must cut some gashes in the trunks of bloodwood trees, so that they produce a considerable amount of resin, which you then subsequently collect. Mixed with water the resultant liquid, when pored into the skin, will begin the curing progress. To fully tan the skin, you must repeat this exercise, after a week.

At this time Richard Gould (another Yank) was conducting an archaeological dig south of Alice Springs. Jim took me down to help Gould and his crew with botanical matters, which I did with pleasure, because I had never before observed a dig, and found the whole process fascinating. Jim brought his newly purchased waterbag with him and proudly displayed it to Gould and his crew. And his pride was justified because it was a beautiful and very practical object. It not only held a great deal of water, but was also easy to carry, because it fitted comfortably around your body. Jim donated the waterbag to the embryonic Canberra Museum, but as it was only the second such object in any museum, he expressed concern about its long-term preservation.

“Worry not,” was the reply from Canberra, “we showed it to the experts and they said it was beautifully preserved, and they admitted that they could not have done a better job.”

The Aboriginal people at MacDonald Downs were an interesting mob. In the past they had worked for Charles (C.O.) Chambers, a crusty Scotsman who brought his family up from the south with horse and cart, blazing a trail around the eastern edge of the Simpson Desert. Chambers ran sheep on his block, using the locals as shepherds to keep the dingoes at bay. He became engrossed with Aboriginal culture, and so the story goes, disgraced his family by going ‘full blackfellow’ in the last years of his life. So, like the people at Mt Riddock, the MacDonald Downs Aborigines were little tainted by white interference, juggling the best aspects of both cultures.

Jim told me of a certain old man who, while he was still nimble enough, just took off with nothing more than a shotgun and disappeared into the bush for a year, shunning contact with any other humans. Fairly early on he ran out of bullets, and so went back to living a totally traditional life. Only several years later I got to know Toby McLean, a white doctor, who, while working for the same mob of people, became very interested in doing the same bushman exercise. The best he managed was one week out bush, not bad for a new chum with just a rifle and a box of matches. Paradoxically, the Aboriginal people thought he was a total nutter – “fancy putting up with all that hardship, just to prove a point.”

Toby also told me about this old Anmatjera man who in many of the last years of his life totally withdrew from society. He spent his time hiding away in a dark corner, apparently in some sort of trance state. It appears that he was so disgusted with his people’s departure from the traditional hunter-gatherer way of life that he no longer wanted to have anything more to do with them. I suppose he was just waiting to die? The MacDonald Downs mob later moved to Utopia Homelands, where some of them eventually became world-renowned artists. Back in 1975 I would never have guessed that dear old Emily, who then lived at MacDonald Downs, would become world famous.

BACK TO THE TOP END

During 1975 it was back to Arnhem Land, where two other botanists and I were given the task of conducting a botanical survey of Elcho Island, 500 kilometres east of Darwin. We had a 4×4 vehicle sent by barge to the island, and we later flew in to the then mission station, which is now the township of Galiwinku.

We almost didn’t make it on time because of an amusing incident at Milingimbi, our last stop before Galiwinku. One of the residents expected that a motorbike he had ordered from Darwin, would be part of the unloaded freight. When it didn’t appear, he grabbed an axe and was about to chop off the wing of the DC3 aircraft, before he was restrained. Apparently his motorbike was long overdue.

Elcho Island Mission was a beautiful place at that time, a well-ordered small tropical town, overlooking an emerald sea. The native occupants appeared happy and prosperous, most of them were gainfully employed, either tending the large prolific garden or doing such things as baking fresh bread for the settlement. (Things have change since then, as described in Richard Trudgen’s excellent book, When Warriors Lie Down and Die.)

The missionaries got a local Aboriginal man, Peter, to settle us into the country, and on our first night he helped us catch a nice big barramundi for our dinner. Late on the second day Peter had to attend a funeral, or mortuary ceremony, and so he left us to our own devices.

We spent an interesting but uneventful week collecting plant specimens and mapping the vegetation communities. This changed however, when early on Saturday afternoon we decided to leave our camp, situated on a nice beach about 10 kilometres from the Mission, and drive off to explore an area to the north.

I was driving as we initially headed back along the track to the Mission. While busy manhandling the truck around a corner and up a small hill, I caught sight of something out of the corner of my eye. Was it true that I had seen three young women walking beside the road, and did I really see one of them exposing her breasts? “Latzii,” I thought, “you’ve been too long in the bush, and you’re starting to see things – pull yourself together.”

Our expedition took longer than we thought, and we got back to camp after dark. What we found was puzzling. In the middle of our tent was our torch – a large model equipped with a flashing-light emergency-beacon – busily flashing away. And someone had helped themselves to tea and biscuits and our nice fresh bunch of bananas.

After I examined the footprints around the camp, I came to the conclusion that the three women I had seen on the way out, had come to our camp and had waited around for us to return, when they would have probably offered us some ‘rest and recreation’. They didn’t realise that botanists out bush, continue to work on Saturday afternoon. This incident made us realise why the Missionaries didn’t want us to camp anywhere close to the settlement.

While we were on the island we met the local linguist, John Rudder, whose job it was to translate the New Testament into the local language. I managed to persuade the other two botanists that we should use John to help us produce a list of aboriginal plant names, and their uses, for our final report. They agreed, so John arranged for us to go out bush with several local women to obtain this information first-hand. This was an interesting exercise, as our chief informant was top-notch, as feisty as they come, mostly treating us blokes as ‘ignorant male whitefellows’. Very different from my ‘aunties’ from the desert, who are much more restrained.

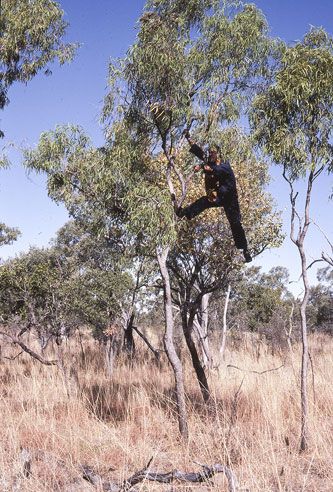

PHOTO by KEN JOHNSON, taken in Septmeber 1985, showing Peter Latz collecting eucalyptus fruit off the Carpenteria Highway.

MORE next week.

PREVIOUSLY:

Tomcat and Turpentine Bush: adventures in the Tanami

Being a cowboy: not all it’s made out to be

Close shaves in the Top End

Dining like kings with a bushman of high degree

Onyer Latzie. More of these wonderful stories.

Love Latzie’s snippets, thanks Erwin.

Great stories … keep them coming. However, the pedant in me has to ask wasn’t it CO Chalmers, rather than Chambers? And it is definitely Dr Toby McLeay (still working in remote Aboriginal health in WA) rather than McLean?