Desert Mob: This is who we are

10 September 2014

Above: Tiger Yaltangki, Vincent Namatjira and Emily Cullinan, by Alex Craig, courtesy Iwantja Arts.

By KIERAN FINNANE

There’s the art and there’s the mob. You don’t get one without the other and in many ways Desert Mob has always carried a message of ‘This is who we are’, even if for the outsider the message has often, even mostly, been beautifully opaque. We have contented ourselves with sensate and aesthetic appreciations and been largely left to wonder in awe at the intricacies of code and invention linking marks on canvas with the itineraries and feats suggested by titles and appended stories.

The interest in desert Aboriginal art from audiences and the market have shown people willing and able to enter into this experience with fervour, and many artists, Alison Anderson among them, have told us to not “try to see behind the veil”:

“Don’t try to learn what the inner secrets of the paintings are: the ceremonial secrets, the hidden meanings behind the surface stories. Don’t try, because with every single thing you discover, you weaken us, and weaken our culture. Don’t record us as if we were dying out. Just be happy with the beautiful surface. That’s what the old artists living at Papunya wanted to show, and it’s the way many of the men of the Pitjantjatjara lands think to this day.”

Tiger Yaltangki’s Desert Safari.

But other artists are availing themselves of a range of means to invite us in, on their terms. Not uncovering ceremonial secrets, of course, but revealing something of what is “hidden” in the art that renders Tjukurrpa (the Western Desert languages term popularly translated as ‘The Dreaming’ or ‘The Law’). One way is through interpretive materials and presentations, and there were again some fascinating examples at the Desert Mob symposium last Friday. I’ll look forward to the day when this excellent event, where artists and art centres lead the conversation on their activities and creations, goes online (as the exhibition does) so that more people can share the experience.

This year’s exhibition also includes many alluring examples of artists doing figurative and narrative works about daily life, spirit and mental life, memory and history – other kinds of invitations into their world. A fine showing across the range comes from Iwantja Arts, located at Indulkana in the far north of South Australia, and home to mainly Yankunytjatjara people. On entering Gallery One – and once past the initial impact of just so many works of conviction, accomplishment and often intense colour hanging in a single room – two works by Iwantja’s Tiger Yaltangki were the first to attract my attention. A wild life of the mind exudes from both: ranks of open-mouthed ghost owls fill the field of Mamu Tjurki, while creatures even more fantastic lurk around every corner in Desert Safari. Strange as they are, they don’t appear to frighten their creator. On the contrary Yaltangki renders them with affection and humour. Both works, but particularly Desert Safari with its plain black ground, look like he has been watching (and enjoying) animations. You can almost see these creatures swooping at you out of the dark, almost hear their weird mutterings. And with his title Yaltangki seems to be suggesting, laughingly, that venture into the desert and you might just be in for this kind of encounter. The photo of him in the catalogue (reproduced at top), his hat cocked over one eye, giving a double thumbs up, suggests his wicked delight at such a prospect.

This year’s exhibition also includes many alluring examples of artists doing figurative and narrative works about daily life, spirit and mental life, memory and history – other kinds of invitations into their world. A fine showing across the range comes from Iwantja Arts, located at Indulkana in the far north of South Australia, and home to mainly Yankunytjatjara people. On entering Gallery One – and once past the initial impact of just so many works of conviction, accomplishment and often intense colour hanging in a single room – two works by Iwantja’s Tiger Yaltangki were the first to attract my attention. A wild life of the mind exudes from both: ranks of open-mouthed ghost owls fill the field of Mamu Tjurki, while creatures even more fantastic lurk around every corner in Desert Safari. Strange as they are, they don’t appear to frighten their creator. On the contrary Yaltangki renders them with affection and humour. Both works, but particularly Desert Safari with its plain black ground, look like he has been watching (and enjoying) animations. You can almost see these creatures swooping at you out of the dark, almost hear their weird mutterings. And with his title Yaltangki seems to be suggesting, laughingly, that venture into the desert and you might just be in for this kind of encounter. The photo of him in the catalogue (reproduced at top), his hat cocked over one eye, giving a double thumbs up, suggests his wicked delight at such a prospect.

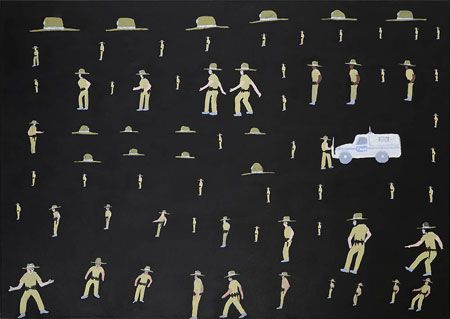

Around the corner an equally intriguing work comes from Iwantja’s David Frank with Policeman Story (above). This is a very different approach to narrative painting (and like nothing I’ve ever seen at Desert Mob), with the story elements – costume, props, gestures, stances – broken into single units and organised into rhythmic rows across the otherwise unadorned canvas. There are a lot of figures, some tiny like tin soldiers, and some larger and more animated, but they probably only represent a few individuals, caught in different poses (including hand on weapon, very well observed). Among the figures, three are dark-skinned and are likely to represent Frank himself who had a long career with the South Australian police. The canvas is crowned by a row of police hats, with smaller hat motifs repeated across the middle and a single paddy wagon on the right anchoring the entire panoply. There’s no narrative action here – unlike Sally Mulda’s interesting police story in Night Time at Abbott’s Camp, in which police (all pink-skinned) are challenging the camp’s Aboriginal residents about drinking grog. Frank’s work seems to be more an image of mental processing – an iconography of police presence in the artist’s life and times.

Around the corner an equally intriguing work comes from Iwantja’s David Frank with Policeman Story (above). This is a very different approach to narrative painting (and like nothing I’ve ever seen at Desert Mob), with the story elements – costume, props, gestures, stances – broken into single units and organised into rhythmic rows across the otherwise unadorned canvas. There are a lot of figures, some tiny like tin soldiers, and some larger and more animated, but they probably only represent a few individuals, caught in different poses (including hand on weapon, very well observed). Among the figures, three are dark-skinned and are likely to represent Frank himself who had a long career with the South Australian police. The canvas is crowned by a row of police hats, with smaller hat motifs repeated across the middle and a single paddy wagon on the right anchoring the entire panoply. There’s no narrative action here – unlike Sally Mulda’s interesting police story in Night Time at Abbott’s Camp, in which police (all pink-skinned) are challenging the camp’s Aboriginal residents about drinking grog. Frank’s work seems to be more an image of mental processing – an iconography of police presence in the artist’s life and times.

There are other interesting figurative works dealing with contemporary life in the Iwantja showing, reflecting a clear curatorial thrust by the art centre. But country as a wellspring for art is also beautifully represented by Alec Baker’s Ngura Piriyakutu (Country in Spring, above left) – the delicacy of new life rendered in finely drawn plant motifs emerging through vivid fields of densely dotted colour.

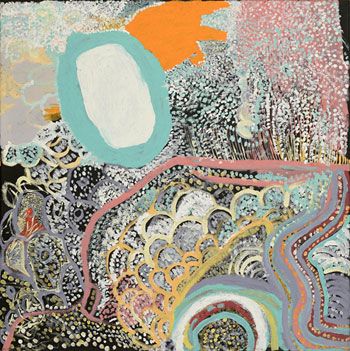

In Gallery Three, Warakurna Artists, from the Ngaanyatjarra Lands in WA, are also showing a range of Tjukurrpa and narrative work, though the balance is more towards the former. Visitors to last year’s Desert Mob will remember the light-boxes from this art centre which were all narrative paintings, some showing scenes of contemporary life in all its interesting difference from and yet connection with traditions, others dealing with historical events, including violent early contact with Europeans. The two in this show are lighter observations, one by Eunice Porter showing wood-collecting out in country (with a truck), the other by Nora Holland, titled Olivia the Pig, reporting on a very specific event – a policeman coming to cart away the animal in question. What is striking in this work is to see what looks like a combination of the two modes, with traditional motifs used to render the wiltja in the foreground in contrast to the blocks of colour denoting the Western-style house, and the figuration to render the truck, the policeman at its wheel and the pig in the cage. Holland’s neighbouring, incredibly lively Tjukurrpa works (such as Wati Pini, above right) underline her gifts, standing out in what is already a strong selection of works of modest scale, hanging well together.

In Gallery Three, Warakurna Artists, from the Ngaanyatjarra Lands in WA, are also showing a range of Tjukurrpa and narrative work, though the balance is more towards the former. Visitors to last year’s Desert Mob will remember the light-boxes from this art centre which were all narrative paintings, some showing scenes of contemporary life in all its interesting difference from and yet connection with traditions, others dealing with historical events, including violent early contact with Europeans. The two in this show are lighter observations, one by Eunice Porter showing wood-collecting out in country (with a truck), the other by Nora Holland, titled Olivia the Pig, reporting on a very specific event – a policeman coming to cart away the animal in question. What is striking in this work is to see what looks like a combination of the two modes, with traditional motifs used to render the wiltja in the foreground in contrast to the blocks of colour denoting the Western-style house, and the figuration to render the truck, the policeman at its wheel and the pig in the cage. Holland’s neighbouring, incredibly lively Tjukurrpa works (such as Wati Pini, above right) underline her gifts, standing out in what is already a strong selection of works of modest scale, hanging well together.

Below: Warakurna Artists, installation view, Holland’s Olivia the Pig at far right. Courtesy Araluen Arts Centre.

In the same gallery an innovative collaboration, Walawuru (left), by Tjala Arts’ Iluwanti Ken and Mary Pan (sisters) caught my eye. This Desert Mob is remarkable for the number of collaborative works. There is the risk-taking collage installation from Ngurratjuta Iltja Ntjarra Art Centre; Tjungu Palya’s entire showing consists of five large collaborative paintings, involving up to five artists; Spinifex Arts Project is showing two; and Tjala (from Amata in the APY Lands) also has several. What stands out with Walawuru (meaning wedge-tailed eagle) is the combination of media: a painting by Ken, and tjanpi (‘dry grass’, in this case spinifex and raffia, sculpture) by Pan. Ken has an exceptional facility for figuration, drawing with great fluidity and dynamism and her intricate rendering of plumage gives her birds of prey a mythic quality. Her brilliance may overshadow her sister’s simpler representations but this observation is probably irrelevant to the way they think about it.

In the same gallery an innovative collaboration, Walawuru (left), by Tjala Arts’ Iluwanti Ken and Mary Pan (sisters) caught my eye. This Desert Mob is remarkable for the number of collaborative works. There is the risk-taking collage installation from Ngurratjuta Iltja Ntjarra Art Centre; Tjungu Palya’s entire showing consists of five large collaborative paintings, involving up to five artists; Spinifex Arts Project is showing two; and Tjala (from Amata in the APY Lands) also has several. What stands out with Walawuru (meaning wedge-tailed eagle) is the combination of media: a painting by Ken, and tjanpi (‘dry grass’, in this case spinifex and raffia, sculpture) by Pan. Ken has an exceptional facility for figuration, drawing with great fluidity and dynamism and her intricate rendering of plumage gives her birds of prey a mythic quality. Her brilliance may overshadow her sister’s simpler representations but this observation is probably irrelevant to the way they think about it.

At the symposium Ken described how she and Pan “bounce off each other a lot”. They wanted to do a multi-media work about “good hunting and raising healthy children”, so they looked at “how the eagle selects its prey … in order to feed its own children” (a theme she and others have treated before).

Pan, who has placed free-standing woven bird tracks in amongst her company of lizards, said it was also about “how we look upon the land and how we can read the country and know who is going where and who’s hunting what and who’s been eaten. So we look at all the bird tracks … they’re not just random footprints, they’re about how we read the tracks in the country.”

The two also spoke interestingly about their work as whole. I think this is Pan speaking (all of these comments were made in Pitjantjatjara and translated by Linda Rive): “Our work is really all encompassing, we work all the time, we’re full time artists, we work in so many different media, we’re always busy. It’s become our whole life, depicting our life and also finding ways in which we can put our ideas down into works of art. So we spend a lot of time thinking, designing and creating and making and producing.

“So all of these various works are all very inter-connected. What we do is … follow on from one idea to the next to create a holistic representation of life in the bush, we’ve got the tracks in the ground, we’ve got the birds in the air, we’ve got the trees and the land and country and all the culture, story and intelligence that goes with that.”

“So all of these various works are all very inter-connected. What we do is … follow on from one idea to the next to create a holistic representation of life in the bush, we’ve got the tracks in the ground, we’ve got the birds in the air, we’ve got the trees and the land and country and all the culture, story and intelligence that goes with that.”

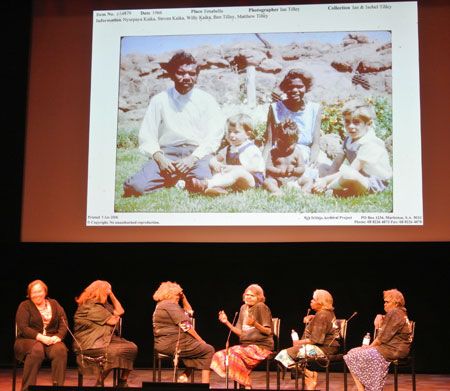

Right: Mary Pan speaking. Iluwanti Ken next to her, then Nyurpaya Kaika-Burton. The women introduced their presentation with an inma (dance) about the Mima Mamu (monster woman), which is why their faces are whitened.

Ken added: “This is really celebrating who we are, celebrating our own culture, looking at ourselves and celebrating us, and looking at us and our work. This has got nothing to do with white people, this is very much who we are. That’s what we are presenting in these works and celebrating our culture.”

On the day at least, no one could rival the celebratory zeal of their fellow artist Nyurpaya Kaika-Burton. She doesn’t have a work in the exhibition this year although she is “part of Tjala and also a Tjanpi Desert Weaver”. Two things were making her feel overwhelmingly proud: one was the acknowledgement of her “dear husband”, Willy Kaika, whose photo was on the symposium program cover and projected as the backdrop image when there weren’t other images running. The photo showed him with the Kulata Tjuta (spears) installation at the 2014 Adelaide Biennale earlier this year. (It was the subject of the Tjala presentation at Desert Mob 2012 and I have also written about it in my essay for this year’s Desert Mob catalogue).

The other source of great pride was her own latest project: “I’m writing my own book, in my own hand, so I’m a writer now.” She spoke of how lucky she is to be “educated to read and write in my own language, Pitjantjatjara … completely literate in my own language, one of the few” and so able to write about her life in her own hand, from her own mind, without a mediator, without a translator.

The other source of great pride was her own latest project: “I’m writing my own book, in my own hand, so I’m a writer now.” She spoke of how lucky she is to be “educated to read and write in my own language, Pitjantjatjara … completely literate in my own language, one of the few” and so able to write about her life in her own hand, from her own mind, without a mediator, without a translator.

Left: Nyurpaya Kaika-Burton entertaining the crowd with a story of how she came to marry her “dear husband”. The backdrop image, from the Ara Irititja Archive shows the young couple.

This triumph was warmly applauded. Kaika-Burton was reluctant to leave the stage. The other women had gone but she was still there, throwing her arms in the air and joyfully declaiming: “So why am I standing here in front of you today? It’s because I’m celebrating who I am and my own culture!”

Someone else who requires no mediator is Lizzie Ellis (left). Born and raised in country around Docker River and Warakurna, she is an accredited linguist of broad experience. In 2010 she moved back to her country and now lives at Tjukula. She works at Tjarlirli Art in a cultural liaison position and also paints. A painting by her is in the show but at the symposium she showed a short film she directed.

Someone else who requires no mediator is Lizzie Ellis (left). Born and raised in country around Docker River and Warakurna, she is an accredited linguist of broad experience. In 2010 she moved back to her country and now lives at Tjukula. She works at Tjarlirli Art in a cultural liaison position and also paints. A painting by her is in the show but at the symposium she showed a short film she directed.

It’s called Kuruyurltu, the name of an important place west of Tjukula and ancestral home of her mother and aunty. “They lived there traditionally,” she explained, “with no clothes, they’d never seen a white man.” First contact came quite late, in the 1950s.

The film shows a painting trip to this place by Tjarlirli and Warakurna artists. Ellis (directing videographer Matt Woodham) films her aunty Tjawina Porter (in a scene from the film below right) and cousin Lyall Giles speaking about Tjukurrpa – stories of how the country, that we are looking at and the artists are painting, was brought into being by the deeds of the Tingari and other creation ancestors. We also see a scene of Ellis and Porter calling out from afar directions to a young relative as she climbs the cliff, following the path her ancestors once had to, to get to water – a clear example of transmission of knowledge that is constantly emphasised by the artists as a motivation for their work.

In the exhibition there are three works by Tjarlirli artists (Esther Giles, Tjawina Porter, and Lizzie Ellis) with the title Kuruyurltu – interestingly all in a muted earthy palette in contrast to most of the other striking work on show from this art centre. I can’t say that I can somehow ‘read’ them as a result of seeing the film but it has given me a richer context for looking at them.

In the exhibition there are three works by Tjarlirli artists (Esther Giles, Tjawina Porter, and Lizzie Ellis) with the title Kuruyurltu – interestingly all in a muted earthy palette in contrast to most of the other striking work on show from this art centre. I can’t say that I can somehow ‘read’ them as a result of seeing the film but it has given me a richer context for looking at them.

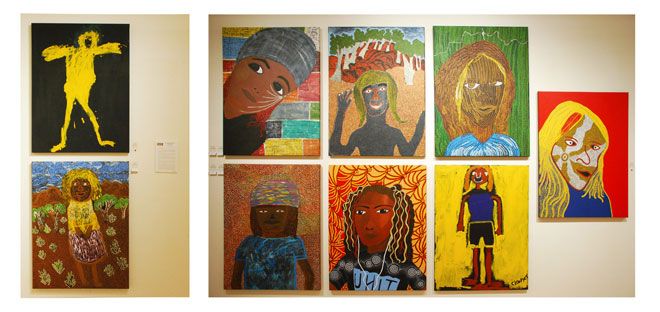

I am giving readers here the merest taste of ‘the art and the mob’. There are almost 300 works in the show and there were nine presentations at the symposium, seven from art centres. It is/was an invigorating experience, an excursion into places and scenarios few outsiders get to know at close quarters, and in the hands of exceptional guides. There are the frail elder artists who continue to paint – such as Ninuku Arts’ Harry Tjutjuna with a pulsating work, Kungka Tjuta. There are the new recruits of all ages – from Trudy Inkamala, a mature woman who only took up sewing at Yarrenyty Arltere within the last year and has triumphed with her Girl in an orange dress (acquired by Araluen), to Colin Watson, a child of six, who took part in the Minyma Kutjera Arts Project’s This is me series. There’s the classicism of the roots of the movement, as elegantly demonstrated by the selection from Papunya Tula Artists; there are the walks on the wild side, some of which I’ve discussed. In a worrying world, what an affirmation of optimistic vitality from the heart of the country.

Minyma Kutjera Arts Project’s This is me series. Colin Watson’s work top left. Installation view, courtesy Araluen Arts Centre.

Trudy Inkamala’s Girl in an orange dress crowning the Yarrenyty Arltere soft-sculpture showing. Gallery Three on opening night. Photo by Alice Springs News Online.

Well written … good stuff!