Loading article…

Loading article…

19 March 2014

By DES NELSON OAM

By DES NELSON OAM

See the previous installment in this series:

Elkedra jackeroo meets masters of improvisation

There were occasions when I would drive the station’s old Chevrolet three tonne truck the 100km west to neighbouring Murray Downs station. Murray Downs homestead was along the route to Hatches Creek township where wolfram was mined. A big truck from Alice Springs carried supplies for Hatches Creek and stations along the way. Elkedra’s goods were off-loaded at Murray Downs. Fuels, foodstuff, hardware and other items had to be collected on the Elkedra truck.

Burge Brown was the boss of Murray Downs living in the main house with wife Ida and children. Also there were two young white men and a group of Kayditj Aborigines, but the two people with whom I had most contact were old timers; independent old men living alone. The type referred to as ‘Death Adders’.

One of these men was a lean framed character, Jimmy Wilson, a lively old bloke with a mischievous sense of humour. He regaled me with stories of the bush in which he had spent his life, mainly in Queensland and the N.T. What he didn’t know about running cattle and horses wouldn’t be worth knowing. He was fit enough to attend muster at neighbouring stations to see, for instance, that if Murray Downs cattle were in a mob at branding time, their calves would be branded with Murray Downs brand. There were few fences so livestock would wander over boundaries.

It was at a branding camp that I first became aware of Jimmy Wilson’s devilry. A busy day in the branding yard had finished, we’d had our tea by the camp fire and men were un-rolling their swags for a sleep. Jimmy invited me over for a pannikin of tea and a yarn before ‘hitting the swag’.

Jimmy spoke softly, “Have a look where Jack Spratt is”.

Jack had his swag un-rolled on a ‘cyclone’ folding stretcher, quite close to the fire.

“Jack”, Jimmy told me, “is more frightened of spooks in the night than anyone else around here. Watch this!”

Jimmy flipped a small stone towards Jack’s bed. In the still of the night the stone hit the hard ground with an audible smack! Jack sat up and stared about.

Quietly giggling, Jimmy instructed me, “Don’t look at him”.

Jack settled down, Jimmy flipped another stone and again Jack sat bolt upright. Having tormented Jack several times, Jimmy went off to his own swag, chuckling, and swearing me to secrecy.

A few years later when I was living in Alice Springs I invited a couple of girls I had befriended to go to the trucking yards to watch cattle from the bush being loaded onto a train to be taken south for sale. Murray Downs cattle had just been trucked. Among the

stockmen was Jimmy Wilson. I approached him and introduced the girls, youngsters, and new to the Territory.

“Come on over to my camp and we’ll have a drink of tea”, Jimmy invited – with a twinkle in his eye. He turned it on for the girls. He showed how to start a campfire and how to place the billycan. He told stories while the billy was heating. He emphasised the importance of conserving water in the bush.

“You might get thirsty and have just a small water supply,” he said. “You can relieve your thirst for a while by rolling a little bit of water around in your mouth. Like this.”

Jimmy demonstrated by taking a mouthful of water and swirling it around. Then he spat it into the by now boiling billycan.

“No waste, see?”

The girls were too horrified to see Jimmy wink at me. He made sure that the girls drank their tea. That was my last encounter with Jimmy Wilson but I have never forgotten him.

•••

The other Murray Downs old timer was Harry Tait, a rouseabout or odd job man at the homestead. He was a friendly old man who liked to talk to me whenever I visited Murray Downs. He had a repertoire of poetry, some traditional Australian items from such as Adam Lindsay Gordon and Henry Lawson and some of a risqué type which I found, in my youth and convent school upbringing, rather embarrassing.

However, Harry was a good hearted person. He would ask me to “Come and have a drink my boy!” He was quite partial to an alcoholic beverage. I would tell Harry that I had taken a pledge at Confirmation to abstain from alcoholic drinks until the age of twenty-one. Harry always respected this but said that we must have a beer together when I did reach twenty-one.

In 1956 there was a memorable party on the Animal Industry research farm just south of Alice Springs. It was the celebration of my 21st birthday. Two days after I walked along Todd Street. In front of the old Stuart Arms hotel a yardman was hosing the footpath. He was Harry Tait. I said, “Hullo Harry. Do you remember me?”

“How are you my boy!” said Harry.

“I’m good thanks. I turned twenty-one the other day”.

Harry dropped his hose. “Come on”, he said and guided me into the bar. So if I remember Harry Tait for no other reason, it was he who shouted me my first beer, the first of many.

•••

Finally, I must describe the boss, John Henry Driver and his wife, Joan. The Drivers came to the N.T. from Western Australia but became firmly entrenched as Territorians. As previously mentioned, John’s brother Frank was the station mechanic and also held a lease to a large block of land on the southern end of Elkedra. This was called Ilbumric. Frank had his own brand, JET and his own cattle. Another brother, A.R. (Mick) Driver had been the Administrator of the N.T. before I came on the scene. John Driver had been the N.T. Surveyor General before taking up Elkedra about 1946. He was a very forthright person, used to giving orders.

He had several ideas for improving his land. He knew all the levels, rises and dips on Elkedra and had plans for the building of water ponding banks. Part of the run was dominated by a spinifex plain, an area of low productivity. John had an idea that a tanker truck containing diluted molasses could be driven over the spinifex, the molasses solution being sprayed onto the spinifex so making it palatable to cattle. In a room at the station workshop was a supply of chaff bags filled with buffel grass seed. I recall that sometimes while doing a bore run I would carry one of these bags of buffel seed in the ute cabin. Handfuls of the seed would be thrown out as I drove along. This was an attempt at pasture improvement, buffel grass being considered a superior type of fodder. The seed came from W.A. When I made a visit to Elkedra in 1957, buffel grass was well established in at least one area.

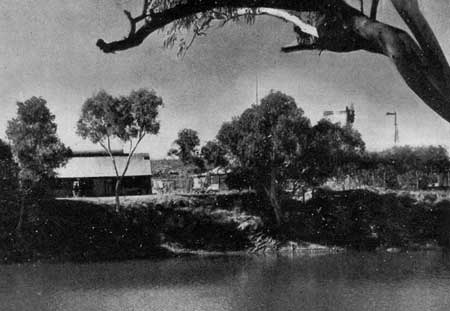

The boss was a conservationist. When sent out to cut fence posts staff were instructed to select mulga trees with more than one trunk. One or sometimes two posts could be cut from a tree, leaving one live trunk to preserve the mulga. This slowed post cutting a great deal but was beneficial to the local ecology. The beautiful tree lined waterhole beside which the homestead (right) is situated was a marvellous haven for birdlife. Shooting of birds near the homestead was strictly forbidden, with two exceptions. Egg stealing crows could be shot in and near the chook yard. Some cormorants were shot in an endeavour to protect the native fish in the waterhole.

John Driver enjoyed visits from CSIRO or government research departments. He could hold his own in philosophical or practical discussions. He enjoyed talking, and arguing. He was able to give such a filibustering type of discourse that he was named “The Sandover Galah”. One other station man enjoyed the title “Sandover”. He was Bob Purvis of Woodgreen station. His large, and renowned appetite earned him the name “The Sandover Alligator”. The names were derived from the Sandover river, a prominent feature to the north east of Alice Springs.

“Never stop learning. Where’s your notebook? A student writes everything down”, the boss instructed me. I already kept a diary, but I heeded the advice. That is why I have been able to produce this current story with accuracy. Much of my memory is in diaries and notebooks.

The Drivers kept in touch with their state of origin by subscribing to “The West Australian” newspaper. Various items used on the station originated in W.A. such as the already mentioned buffel grass seed and things like “Taylorite” paint used for painting corrugated iron roofs and a cement tank. This paint dried to a brilliant white reflective finish.

Keen to keep in touch with the political scene, John Driver contributed to Federal parliament Hansard. I was introduced to this literature as it was ultimately left in the pit toilet room. Some may think this to be an appropriate place for it!

Much has been written of hard times endured by Aborigines at the hands of station owners in the past. Such criticism can not be levelled at the Drivers. There were sixty to seventy people in the Alyawarra camp not far from the homestead. They were, in general a clean, healthy, and usually happy lot.

At that time they had not succumbed to the destruction wrought by alcohol. They were not permitted to use it. Stockmen and house

helpers were recruited from the camp. They were paid correctly and were well clothed. The Aboriginal stockmen addressed the boss as “John”. To me, the young whitefeller jackaroo, he was “Mister Driver”.

In 1955 I decided to move on. I told the boss that I was considering further studies. He encouraged my ambition. In later years I would encounter John Driver in Alice Springs. He would ask how I was going and what I was doing.

He developed an affliction which caused gradual paralysis and became wheelchair bound. The last time I saw him he was in his wheelchair at the bar of the Alice Springs Memorial Club. He was drinking beer through a straw from a glass on a tray attached to the chair. Other men were clustered around him. With these he was conducting a vigorous, argumentative conversation. His brain was as agile as ever.

Joan Driver was a tall, very correctly spoken lady. She had a busy life. When I arrived on Elkedra the Driver boys Dennis and Roy were twelve years and nine years respectively. They were active lads with a vast backyard to play in. School of the air lessons for them had to be supervised. The oldest child, Penny was at school down south.

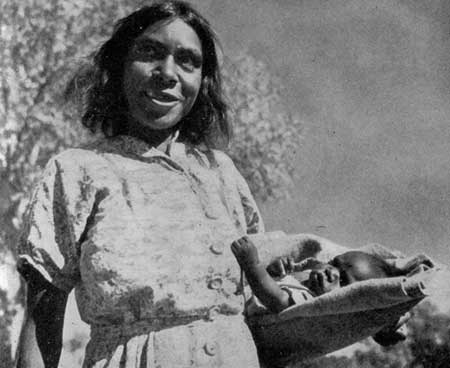

Left: Katie, a ‘house girl’ at Elkedra, photographed for the feature on the station by J.K. Ewers, published in Walkabout, May 1, 1952 (also the source for the photograph of the homestead above).

Daily instructions were given to the house girls, Myrtle and Jemima, but Mrs Driver was the cook, and a very good one. She took part in CWA of the air meetings which were conducted via radio transceiver.

Also at the homestead was Granny Driver, mother of the boss and Frank the mechanic. A pleasant, intelligent lady she was a good companion for Joan. John and Joan were a devoted couple. Joan was much the quieter but with her strength of character she was a good foil to the more volatile John.

Sometimes Mrs Driver would ask me to do little jobs for her. Things like topping up the tank of the kerosene refrigerator or doing maintenance on small household items. She was always pleasant but I had on one occasion to appreciate her care in particular.

On the day of my 19th birthday I was out with the stock camp near Erlpunda waterhole. I had shot two emus the day before. Their legs, like giant chicken drumsticks, had been boiled in a large bucket which contained the fluid in which salt beef had been cooked. So, on my birthday I ate cold boiled emu leg, way out in the bush.

Next day Frank Driver arrived at the camp in his ute. Wishing me a happy birthday, he handed me something and drove off. It was a birthday cake – a delicious fruit cake, made by Mrs Driver. It was surrounded with a coloured crepe paper collar. I was touched by the kindness shown to me. I shared the cake with my work mates and wore the paper collar around my hat until it fell to bits.

John and Joan have passed away and lie together in the Alice Springs cemetery. Their memories live with me.

I really appreciate these stories, not least, because of the kindly historical account, but also for the humanity of the people encountered. Thank you. I look forward to more from your pen.

Great to find this. Burge Brown and Ida were my grandparents.