Loading article…

Loading article…

13 February 2014

DES NELSON OAM arrived on Elkedra Station, some 500 kms north-east of Alice Springs, as an 18 year old in 1953. Here he continues his series of recollections, starting with a droving trip in the autumn of 1954. (See the first in the series here.)

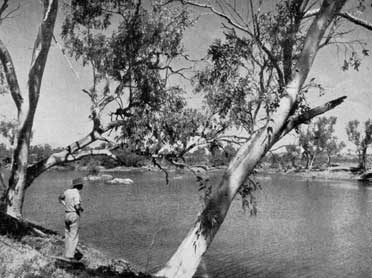

Des, from his home in Cowra NSW, had been inspired to make contact with Elkedra after reading With the Sun on my Back by J.K. Ewers. We owe the location of photographs of the Elkedra of the time to Des’s son Alex Nelson, whose personal archive includes an issue of Walkabout magazine, dated May 1st, 1952, featuring an article about the station by J.K. Ewers.

Early in April 1954 a big mustering job began, to gather a mob of cattle to be droved 500km to Alice Springs. From there they would be put into rail wagons for sale in South Australia. Lots of hard riding was done—there were no trap yards. Four hundred head were assembled.

The month long journey along the Elkedra and Sandover stock routes began on May 16th, 1954, with Jack Spratt as boss drover. Being the only literate person in the group I was given charge of the Way Bill to be presented if necessary to stock inspectors. I also drove the truck.

The average distance travelled daily was 16 km. There was excitement one night when the cattle rushed and there came a headlong dash on the night horses to wheel and quieten the cattle. It was interesting to see how the cattle sorted themselves out at night camps, always aligning themselves in the same position, night after night. To keep the cattle quiet after dark there was a roster of horsemen to ride around the perimeter of the mob. The horseman on duty would sing or talk to keep the cattle settled. I would softly sing songs familiar to me. The Aborigines would chant their own soothing tribal songs.

The average distance travelled daily was 16 km. There was excitement one night when the cattle rushed and there came a headlong dash on the night horses to wheel and quieten the cattle. It was interesting to see how the cattle sorted themselves out at night camps, always aligning themselves in the same position, night after night. To keep the cattle quiet after dark there was a roster of horsemen to ride around the perimeter of the mob. The horseman on duty would sing or talk to keep the cattle settled. I would softly sing songs familiar to me. The Aborigines would chant their own soothing tribal songs.

It was a tense, tiring job. I established much respect for the Aboriginal stockmen.

At the conclusion of the trip there was a brief holiday in Alice Springs. We went to the pictures and indulged in lollies and milkshakes. I bought a brilliant gold satin cowboy shirt embossed with longhorn cattle motifs. One of our men formed a liason with a pretty young woman from Hermannsburg and took her home. This led to troubles in the future.

There was a man who seemed to be regarded as a person of some influence, named Billy Beasley. He became a close associate of mine. I think he may have chosen to look after me. He always was around when I was out bush with the mob. He would instruct me about various matters. He pointed to a distinctive strata line high up in some hills in a valley. That line, he told me was the height that water reached back in the long ago when a huge flood killed everything. Later, life began all over again. I was amazed to realise that this was a parallel with the Old Testament flood story.

Billy told me of areas that were to be avoided because a death had occurred there, or a place may be the pathway of the avenging Kadaitcha men. He told me how a person who broke their law could be ‘sung’ and might die unless a powerful person could perform another ceremony to bring the miscreant back from danger. Ritual ‘singing’ was a very important part of tribal life.

One day, in the stock camp, Billy’s horse stumbled and rolled over him. I got him into the truck cabin and kept talking to him as I went on a long slow drive to the homestead. Although badly bruised, Billy recovered quickly and the bond of friendship between us was strengthened.

I was wearing my loud cowboy shirt one day when Billy approached and said, “Ngwarryay! Gimme that shirt!” Billy was wearing a new pair of jodhpurs. This was a test of my acceptance with the people.

“Right-o Billy! Give me those trousers!”

The swap was made there and then. Next day I saw that another man, not Billy, was wearing the shirt. This was the result of the addiction of Aborigines in those days to the card game, poker. People as far removed from white society as could be imagined were devotees of poker. All kinds of articles would be put down by the gamblers. A box of matches would be considered to be equal to an item of clothing as barter in the gambling game.

After the droving job was out of the way there was a bit of a slow time. It was time for a concert period. There were dances that were for general exhibition. There were men’s corroborees, women’s corroborees and some of great religious significance.

I heard one of the latter taking place during the time of the Hatches Creek amateur race meeting. Hatches Creek existed because of wolfram mines. As well as a few dwellings there was also a store and a police station. The annual race meeting was an event which brought together the people of the district including a great throng of Aborigines. They took advantage of this gathering to perform the very important initiation, or “man making” ceremony on youth chosen to undergo this procedure.

At night, when the ceremony was taking place there was a crescendo of noise which sounded like the up and down revving of a giant truck engine. This was made by a lot of bull roarers. These were small, flat, broad pieces of wood with pointed ends. A hole was pierced near one end. Through this a metre long piece of home-made, very strong hair string was tied. The operator swung the string in a vertical circle and when the velocity was right he would touch the tip of the instrument on to the ground. This caused it to spin rapidly and produce a loud buzzing sound. The resulting sound of many bull roarers kept away bad spirits and was a warning to women and the un-initiated to keep a long distance away.

The tribal people had a strict moral code. I didn’t comprehend their laws but I appreciated that they prevented intermarriage among closely related groups. These groups were named, each title being known as a ‘skin name’. People of certain skin groups were not allowed to look at one another. If a person was being approached by another of the ‘wrong skin’, often a warning would be spoken. I once saw one of the house girls walk around a corner to be confronted by a wrong skin person. There was immediate closing of the eyes, bowing of the head and mutual turning away. Such accidental events were forgiven, but I was told that deliberate eye contact between wrong skin people would have dire consequences.

I was invited to some of the general exhibition concerts. They were spectacular affairs. Dancers would prepare themselves by decorating each other. Two men would sit on the ground and glue white downy feathers on each other, making patterns. The glue was blood, kept in a wooden dish or a tin can. There were two methods of obtaining blood that I saw. One was to break a glass bottle, then select sharp slivers which were used to pierce a vein in an arm. The other method was to wait until a beast was slaughtered for meat. This was a real bonus as it provided a profusion of blood for feather gluing.

Tall head dresses were made from sticks, laced with string and on which more feathers were placed. Around the ankles, circles of gum leaves were tied.

The stage was a flat, cleared area. A bright fire showed up the dancers and their make-up. They stepped, shuffled and swayed to a chorus of chanting. On one side of the audience, women would beat a rhythm by slapping their thighs. I would join the men on the other side, clicking boomerangs together. There would be talking and laughter between items. It was all very pleasant until one night I noticed Billy Beasley in earnest conversation with some of the men, with glances taken in my direction.

Billy approached me and said, “Ngwarryay, we bin do all this blackfella corroboree and you bin like it, aint it?”

I had to agree.

“Orright”, said Billy. “Now you got to do a white fella corroboree for us”.

I tried to laugh off the idea, but Billy was most insistent. I felt very embarrassed. My mind was racing. Inspiration came.

“All right”, I said, “give me a boomerang”.

I stood in front of the people and held the boomerang in front of me. I made motions as if starting a vehicle, put a phantom gear lever into position, and moved off. I went around the stage making engine noises and went up and down the gears, double declutching (as you had to do with the old trucks we used). Gears whined, the engine strained under the load. After several minutes I stopped in the centre of the stage, put the gear lever into neutral, gave a final rev of the engine then switched off. It was a sensation!

I stood in front of the people and held the boomerang in front of me. I made motions as if starting a vehicle, put a phantom gear lever into position, and moved off. I went around the stage making engine noises and went up and down the gears, double declutching (as you had to do with the old trucks we used). Gears whined, the engine strained under the load. After several minutes I stopped in the centre of the stage, put the gear lever into neutral, gave a final rev of the engine then switched off. It was a sensation!

For weeks afterwards little black children could be seen with a boomerang or a stick doing my truck driving corroboree.

The people had a great sense of humour. The waterhole at the homestead dried up in 1955. Water had to be carried in 44gallon (200litre) drums from another waterhole. One day I took some men and three drums on the blitz wagon to collect water. The blitz was backed down a slope to water’s edge and the drums were filled by a bucket relay. The job done, I moved the truck slowly but hit a small bump and the drums fell off the vehicle. We clustered around a drum to lift it onto the truck’s tray. At the word, “Lift!” strain was taken and someone produced a very loud fart. The men fell about laughing hysterically. It was some minutes before they recovered enough to enable the loading of the drums to be achieved.

Something similar happened one night when the gramophone was in use in the camp. I was disc jockey on this occasion. A song finished and I was in the process of changing records when the silence was punctuated by a big fart. Someone called out, “Hey! Who bin yodel?” A pause, then “Oh! Yodel longa wrong end!”

An amusing event took the form of a play. Two officers from the government Native Affairs department arrived by car from Alice Springs. Scrubbed, clerical types they had come to make a census and conduct interviews with the Aboriginal men. The men were stood in line while the officers moved along, questioning and writing on a clip board. All went along efficiently, then the Native Affairs men left. There were chuckles from the locals. I had watched the event. I think it was on the following day that a performance took place which I was also lucky enough to see.

Again, men were put into a line. Two star actors represented the public servants. They moved along the line, stopping before each man to ask questions. A piece of bark served for a clip board, a stick for a pencil. String was tied around ankles and into this was poked a small stick to represent a pencil tucked into a sock. They had not missed a thing! A dialogue went like this:-

“What you name?”

“Quartpot”. A scribble on the bark clip board.

“You gottim any wife?”

“Yu-i, might be two, might be three”. Great laughter from the audience and a shriek from his wife.

“You got any kids?”

“Oh, big mob! Too many!” More hilarity.

So on it went in a spirit of great fun.

My confidant, Billy Beasely later told me, “We bin tell that government mob a big mob of rubbish. None of their business what we bin do!”

Somewhere on old official files there may be ‘rubbish’ data from Elkedra Aborigines.

There was an incident in 1955 which was not much discussed in my presence, being the young jackaroo. I knew that it involved a disturbance between Alyawarra people of Elkedra and the Kayditj people of Murray Downs, the station neighbouring us to the west. A Kayditj man had been shot to death. A policeman arrived to question the locals.

He asked each man, “You got a rifle?”

The usual answer was “No”, until one man, displaying the honesty that was usual to these people, replied, “Yeah, I got a rifle”.

“Where is it?” from the man of the law.

“Him there!” said our man, pointing to his wurley.

This caused quite a stir as at the time almost all N.T. Aborigines were deemed to be Wards of the State. They were not supposed to consume alcoholic beverages, were not allowed to vote in elections in their native land, or to possess or use firearms.

I knew several men who were taken to Alice Springs as witnesses in court. When he returned, one of them regaled us with his experience in town with much hilarity.

A boss man in the court, presumably the magistrate and very likely, J.W. “Judge” Nicholls, a rather rotund person had addressed our man, as he described.

“This proper big fat feller frog binjy bin yabber longa me—‘You gotta tellim true feller now! No more tellim lie! You bin tellim proper true feller!’”

This was received with much laughter especially as the narrator used his hands to demonstrate the size of the “Big fat feller frog binjy”. He also caused merriment by describing the antics of drunken white fellers outside the Stuart Arms Hotel. I never did learn the outcome of the court enquiry.

Branding time was a very physical event. It was exciting and conducted with exhilaration. Calves or sometimes larger animals were lassoed by a rider mounted on a bronco horse. The beasts were pulled up to the branding rail in the middle of the stockyard, leg roped and thrown, hot branded, ear marked, and males were castrated. After a day of this activity we always slept well.

One day I was out riding with Peter when we came across a young mickey bull. Peter dived off his horse and threw the bull down by twisting its tail, then tied its rear legs with a leather strap. Neither of us was carrying a knife. Peter showed me how to hold the animal down while he looked about and found two white quartz stones. He smacked them together, breaking them. The broken parts had sharp edges. Using one of these impromptu knives, Peter ear marked, then castrated the bull. When it was released it chased us around a bit before running off into the bush.

Some time after the homestead waterhole dried up I watched Frank the mechanic scolding some of the men.

“What’s the matter – have you mob forgotten how to make rain? Where’s those old rain maker men gone?”

No reply was made but some weeks later two men approached the homestead area. A fire was lit and allowed to burn down to ash then left to cool. The two then returned, carrying bunches of eagle feathers. There was some quiet singing, then ashes were thrown into the air and long aerial sweeping motions were made with the feathers. I was told that the ashes represented an invitation for clouds while the feather waving would draw up real clouds. Their job done, the men quietly left.

Next day, 10mm of rain fell at the homestead but more had fallen to the north as the Elkedra River flowed and partially filled the waterhole. Had those men read the meteorological signs and put on a show? Did their ceremony have any influence? Who knows, but they certainly had a win.

Next day, 10mm of rain fell at the homestead but more had fallen to the north as the Elkedra River flowed and partially filled the waterhole. Had those men read the meteorological signs and put on a show? Did their ceremony have any influence? Who knows, but they certainly had a win.

Sometimes events were not so light hearted as many described so far. Because of his status on the station, it was decided to build decent accommodation for Jack Spratt and his full blooded Aboriginal wife. It was a corrugated iron structure with large hinged panels that could be propped open for ventilation and on one end was a big stone fireplace and chimney. It was a mansion compared with the wurleys of the general Aboriginal population, who insisted that they were quite happy with their wurleys.

Jack’s wife had a baby which unfortunately was a very weak infant. It died inside the dwelling we had erected. Jack’s wife refused to enter that structure again.

A row broke out concerning the girl from Hermannsburg who had been brought home by one of our stockmen after the droving trip. I think the trouble was due to the upsetting of ‘skin’ relationship rules, but I am not certain about this. The camp divided into factions. I recall a night when a loud discussion took place. It seemed quite civilised when compared with white man’s rowdy parliamentary procedures.

An old man from one side stood up and with no interruptions gave a lively oration in support of his company’s view. He sat down, then an old man from the opposition rose up to state his view. The problem could not be solved by discussion. It was decided that the solution would be settled by a fight.

This took place at a bore on the south end of the station. I watched, sitting on a swag on the back of the station truck. While battle lines were being arranged, Billy Beasley approached me and asked for the .22 calibre pistol that I carried in my swag. I said, “Fair go, Billy! You told me one time that Blackfella business is Blackfella business and Whitefella business is Whitefella business. Well, my revolver is Whitefella’s business”.

Billy graciously accepted this statement and went back to the area where the opposing sides, looking very ferocious, with spears and boomerangs, faced one another. They advanced towards each other, then spears were thrown – not very accurately, I noticed. On one side a man was cracked on the ankle by a boomerang. On the other side a warrior was injured in the rib area by being poked with a steel yam stick.

It was all over, and the two groups mingled amicably. Somehow, all was resolved. Again I thought how civilised it all was.

The Alyawarras were very possessive of their country. I concluded that the various tribal groups were in fact separate nations and may not be on the best of terms with their neighbours. One hundred kilometres east of Elkedra homestead, was Murray Downs homestead, the base of a population of Kayditj Aborigines.

White people have rivalries. Sydney versus Melbourne, for instance, Alice Springs and Darwin, or Aussie Rules compared with Rugby League. These can not compare with ancient tribal hostilities such as existed between the Alyawarras and the Kayditj. This was demonstrated when a dispute arose in the stock camp. The men had become disgruntled about something of which I cannot recall now but I do remember that they threatened to walk off the job.

“That’s all right”, said Jack Spratt. “You mob clear off. I’ll go over to Murray Downs and get plenty of workers from there.”

Instantly the strike was cancelled. No way could our men countenance the presence of Murray Downs people on Elkedra.

Although the people were very much attuned to nature, there were some incidents which were interesting, or puzzling. Willy willys, or whirl winds, were disliked. They were bad items which could be diverted by pointing a little finger at them while saying, “Mundy, Mundy”. (I still do this).

The men did not like chattering Willy Wagtail birds. They would throw things at them to shoo them away. The Wagtails were said to listen to what the men were talking about then go away and tell their conversation to the women.

I caught a praying mantis and put it on my shirt. I was told to get rid of it or it will “Give you a headache”.

I caught a knob-tailed gecko. When disturbed these pop-eyed little reptiles rise up on their spindly legs and make a rasping sound. I put the one I had captured into my hat and carried it over to a group of people who were sitting under a tree. When they looked inside my hat, there was a yell and I was amazed to see the whole mob run as if I was pointing a gun at them. I never did find out what was so formidable about that funny little lizard.

Itchy feet got the better of me so I left Elkedra in 1955 and went south for some months. On my return to the N.T. later that year I gained employment with the Animal Industry Branch of N.T. Administration, first in Chemistry section, then in Botany section. Bushwork was involved in these positions, which suited me very well. To my good fortune, early trips with both sections involved visits to Elkedra. Being a professional, John Driver was willing to co-operate in scientific endeavours. I was able to briefly renew some of the acquaintances of my jackaroo days. However, I inevitably lost contact with the station people. Rarely, I would meet one of them visiting Alice Springs.

The community of Warrabri, now Ali Curung, was established on Murray Downs country around 1955. I believe many Alyawarra people went to live there—among the Kayditj!

Nearly sixty years have passed since my time as an Elkedra jackaroo. It was a pivotal time of my youth. I remain forever grateful to have had these experiences with the Alyawarras. I am grateful for what they taught me, and I am grateful that in spite of the warning from the boss, I “got friendly with the Blacks”.

NEXT: Frank Driver, brother of the boss, and other ‘characters’ from Elkedra and Murray Downs.

Thanks.

Many thanks. Very interesting. And, for me anyway, a new take on Australian race relations. We only hear the bad side – and I’m sure there is truth in it – but there is obviously a good side as well.

Hello, my name is Deanne. I am Jack Spratt’s granddaughter. My mother is Jeanne Spratt, Jack’s daughter. She would like to meet Des. We live in Alice Springs.