What makes a patch of dirt a place?

26 November 2013

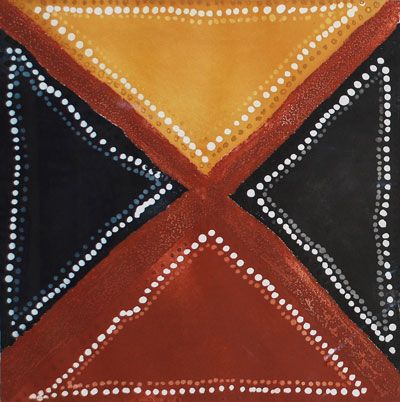

Above: Part of a wall of small works by Tobias Richardson.

RUSSELL GOLDFLAM, President of the Criminal Lawyers’ Association of the NT, opened the Alice Springs outing of the traveling exhibition roads cross: contemporary directions in Australian art. It is showing at Araluen until March 2, 2014. This is his opening speech:-

Good evening, and to mparntwerenye mape, werte. We stand on your country. We don’t just stand on it. We cross your country. We sit down on your country. And, as we are here now to explore, we paint your country.

This exhibition, jointly curated by Fiona Salmon and Vivonne Thwaites from one end of our street, and Anita Angel from the other end of our street – by our street, I mean of course the Stuart Highway – is called ‘roads cross’.

How fitting that they have agreed to meet each other halfway and set up camp here, exactly at the midpoint of their street; and although Vivonne couldn’t make it along tonight, I’m delighted to welcome Anita down from Darwin, Fiona up from Adelaide, and one of our artists, Nyukana Baker, over from Ernabella.

So here we are, all here standing at Mparntwe, where, according to Arrernte sacred geography, the tracks of Yeperenye, Ntyarlke and Utnerrengatye caterpillars, of Irlperenye beetles and Akngwelye dogs, among other beings, where all their tracks criss and cross, marking the country with the signs of their campsites, their battles, their births, their deaths.

And ‘here’ is also Alice Springs, not just a crossroads in the sense of being a transport hub, but for our purposes more significantly, a site of cultural contact, exchange, struggle, birth and death: a place where as much, I think as anywhere, roads cross.

The pivot of this exhibition, the X that marks the spot from which it grew, is Rover Thomas, the grand old master of the Kimberley. When he made his famous Crossroads works – and you’ll see some of them here (image of one, left) as soon as you enter this beautifully hung show – he said he was painting ‘anywhere’. He wasn’t depicting a place in particular. He was depicting the general idea of place itself. And by deploying the icon of the cross to designate place, he was, it seems to me, making a fundamentally important point: that what makes a patch of dirt a place, is that it has been traversed, crossed, marked, ‘impressed’, to borrow the word used by Salmon and Thwaites in their very thoughtful Catalogue Introduction.

The pivot of this exhibition, the X that marks the spot from which it grew, is Rover Thomas, the grand old master of the Kimberley. When he made his famous Crossroads works – and you’ll see some of them here (image of one, left) as soon as you enter this beautifully hung show – he said he was painting ‘anywhere’. He wasn’t depicting a place in particular. He was depicting the general idea of place itself. And by deploying the icon of the cross to designate place, he was, it seems to me, making a fundamentally important point: that what makes a patch of dirt a place, is that it has been traversed, crossed, marked, ‘impressed’, to borrow the word used by Salmon and Thwaites in their very thoughtful Catalogue Introduction.

At first sight, this show looks like a landscape exhibition, but, taking its cue from Rover Thomas, it’s not about specific places so much as it is about the concept of place and the process of place-making. About how to transform patches of dirt into places loaded with meaning and value, by marking them.

Most of the artists here are, however, interlopers, so the terrain can be tricky. Many of them spent years picking their way through thorny ideological thickets, writing academic dissertations with appropriately anxious titles such as ‘Long to Belong’, and ‘A Necessary Nomadism’. The curators too, I am led to believe, had a pretty bumpy ride, negotiating their way over the razor-sharp rocks which pave the road to political correctness.

The elegant but feisty catalogue essays by Anita Angel and Ian McLean chart the tortuously post-colonialist, post-modernist, post-structural way: indeed, there are so many posts and so many signs along this bloody road, it’s a wonder anyone actually gets to see the country we’re passing though at all.

The folk in the big white cubes and tower blocks down south endlessly agonise themselves into cul de sacs over intractable questions of neo-colonial appropriation, and the asymmetricality of cross-cultural discourse, and the skewed power dynamics of interracial collaboration, and the impossibility of true reconciliation, and so on.

This exhibition shows us that the way out of the that dead end is not to try and theorise or think or argue or talk your way out, but to paint your way out. As the famous philosopher quoted in the Catalogue archly put it, ‘in art it is hard to say anything as good as: saying nothing’.

These artists have thought, and read, and argued their way into the thicket. And then they’ve painted, or sewn, or photographed, or sculpted their way out of it again. To put it another way, they’ve worked their way in, and, to borrow a musical term, played their way out. And, although there is great diversity in this exhibition, which is part of its strength, it seems to me that much of what is on display here is the product of a prominent, if not necessarily dominant, strategy.

These artists have thought, and read, and argued their way into the thicket. And then they’ve painted, or sewn, or photographed, or sculpted their way out of it again. To put it another way, they’ve worked their way in, and, to borrow a musical term, played their way out. And, although there is great diversity in this exhibition, which is part of its strength, it seems to me that much of what is on display here is the product of a prominent, if not necessarily dominant, strategy.

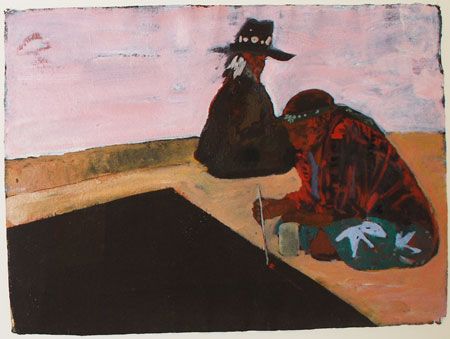

Many of the artists in this show have sat down on country and observed Aboriginal people meticulously, methodically, unselfconsciously – and beautifully – going about their painting business. There’s a small and modest but highly revealing picture (above) by Una Rey here which depicts just this.

The lesson is simple and clear: if you want to mark a place, to make a place, that is what you do. You sit down on country, you lose yourself in its beauty, you dip your brush, and on this cavernous empty space, the void of your canvas, you venture to dab a little dot of vivid, livid colour. I suspect that it often turns out that losing yourself like this is a pretty effective way of finding yourself, a gleaming little bit of you having mysteriously impressed itself into the canvas while you were working, so that now you are in place, just as place is now in you.

Roads cross at a place we call X, the site of transection and transaction. But X is also our symbol for the unknown, the intangible, the variable, the mystery. At the heart of all art worth its name sits an X, the X about which, as the famous philosopher warns, it is probably best to say nothing.

So in deference to Mr Wittgenstein, I won’t embarrass myself by continuing to talk about the mysteries of art. That’s really not my field anyway. My field is law. The law is also a site where roads cross: our settlers’ law has marked and scored this country, obliterating, or more frequently, merely ignoring pre-existing Indigenous laws.

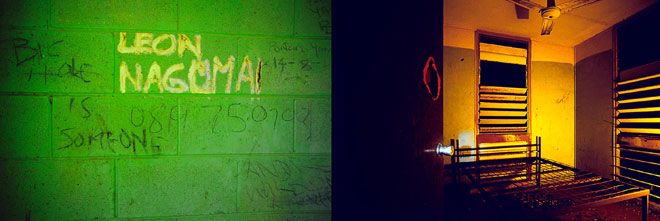

The walls of the foyer of the Alice Springs courthouse, a suitably miserable and dilapidated place, given the miserable and dilapidated stories which are recounted there every day, are hung with small framed early works from Papunya in which, no doubt, are encrypted fragments of the Pintupi legal code, not that anyone who sits there ever remarks on them.

In that courthouse, magistrates and judges are prohibited by law from having regard to traditional laws or cultural practices when assessing the seriousness of an offence. Over the last thirty years, we have moved further and further away from the dream of recognising each others’ laws, of being a place where roads respectfully cross.

In my view, this dismal trend is part of a broader paradigm shift in relation to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Nowadays, the once unchallenged model of self-determination is regarded by many as a failed social experiment, and in its place a sense of profound malaise has descended. We have long celebrated Aboriginal excellence in sport, but even there some of the gloss has worn off recently, in part, sad to say, because of events in that very same Alice Springs courthouse.

In the field of visual art, though, and perhaps only in this field, Indigenous Australians lead the way, both locally and globally. This is extraordinary, and it is precious. It gives us, as a nation, a rare opportunity to show authentic respect to the peoples whose country we have crossed. We do not show that respect properly in our Constitution, or in our lawbooks, or in our courtrooms. But we do show it in our museums and galleries. And in particular, we show it here, in this exhibition, which is why, above all, I am delighted to declare ‘roads cross’ open.

Russell Goldflam 16 November 2013

Below: From the series mightbe somewhere by Pamela Lofts.

Interesting words, spoken well. Thanks Russell for sharing your thoughts on these works with us.