Across the world, through time: a search for meaning

18 June 2013

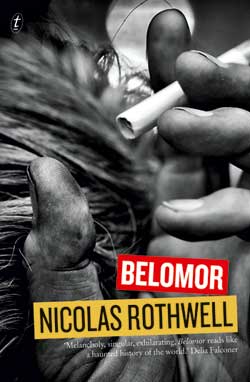

Belomor

Belomor

By Nicolas Rothwell

Text Publishing, 2013

REVIEW by KIERAN FINNANE

Not many of us own up, in our private domains let alone in public, to our searches, our longings for deep meaning in our lives, yet here is a book that goes in and out of our part of the world that does just that. It is a sustained quest for the core of things, for the shape of life, that “reaches down pathways of used time”, but also loops, seemingly effortlessly, around the globe, from the northern reaches of Russia to deep in the western deserts of Australia.

We last saw Nicolas Rothwell, the Northern Territory’s most prominent journalist and writer, in this mode in The Red Highway (Black Inc., 2009). That book was pervaded by a wounded-ness, a close experience of mortality, loss, an apprehension of more to come. This new book, with its title Belomor so full of mystery yet rolling so pleasingly from the tongue, seems to come from a different place: a grave serenity has been reached about the inevitable passing of all things – whole cities, civilisations, great minds, cherished friends, loves – but its author is still passionately bent on a search for meaning, and with that search comes a kind of safe-guarding of what has gone before.

Rothwell, through his un-named narrator, embraces all the modes of knowing that he senses or comes across: we need them all, seems to be his message. Rational analysis, logic, science, the facts of the surface can get us only so far. Being alive to coincidence, intuition, resonances, transcendent visions, inner voices – so easily, blandly dismissed – is what allows his quest to take form, to arrive, finally.

‘Arrive where?’ you may ask. At a point of return that could also have been a starting point, a point of connection, between ways of being and knowing generally thought of as utterly different, as opposed to one another as hot and cold, north and south. It’s reached, via many twists and turns, in two over-arching conversations: one in an apartment in Dresden, East Germany with a dissident thinker, Stefan Haffner, just before the collapse of the Iron Curtain; the other in an out-station, somewhere near Laverton in WA, recounted by a so-called carpetbagger, David Aster, who turns out to be a seeker in his own right. Both take place in worlds in transition.

East Germany was about to disappear from the map and its residents, to suffer a peculiar kind of dissolution. Through the narrator we meet a number of them, each trying to grasp hold of meaning in their fragmented world. Their search and its moments, slipping in and out of their hands, are what counts, as substantial and as transitory as Haffner’s vision of the White Sea at the entry to the Belomorkanal, as its reverberation later in the book, experienced by a younger, newly free East German woman, a film-maker – the “drifting curtains” of spray from waves travelling from east and west and meeting at the tip of a tiny island in the Tiwis. Alongside these, the rebuilding of Dresden’s Frauenkirche, destroyed during the Allied bombing of the city in World War Two, such a material triumph, seems also a vain endeavour. In overcoming one annihilation, it engenders another, in one movement it raises and obliterates the past.

How do we get from Dresden to the Tiwis, to the deserts of The Centre? That is one of the marvels of the book. We see East Germans exercising their new freedoms in extraordinary ways. They’re our model, the narrator’s model. The film-maker drives down dirt roads in the desert for days on end, simply to explore a sense of the unlimited: “The limits we see and agree on are the ones to break,” she tells the narrator. “There isn’t any boundary to what we can conceive, and make inside ourselves; or there doesn’t have to be – if only we can escape the gridlines of our thought, all the patterns that bear down on us and trap us every day.”

The book follows this exhilarating path into history, thought and experience. It doesn’t close anything off. It doesn’t explain – that would be a dead end. Instead it opens up multiple lines of inquiry: if we take this turn, knock on this door, go down this street, get into this car, take up this conversation, what will we find?

The book follows this exhilarating path into history, thought and experience. It doesn’t close anything off. It doesn’t explain – that would be a dead end. Instead it opens up multiple lines of inquiry: if we take this turn, knock on this door, go down this street, get into this car, take up this conversation, what will we find?

The narrator is often initially reluctant to do this, held back by thinking that he knows what lies ahead, but right on the brink of rejecting the possible encounter before him, he goes for it and what riches those intuitive choices deliver.

At right: Nicolas Rothwell. Photo by Darren James, courtesy Text Publishing.

Most of us, I suspect, are unpractised at reading this kind of text – intuitively structured, lyrically written philosophical questing that spans continents, centuries, languages, cultures, beliefs – although the recently published graphic novel, The Long Weekend in Alice Springs, makes comparable leaps and bounds. Rothwell’s narrator often expresses, ahead of us, reservations, scepticism, before plunging in. Choose to go with him to be rewarded.

He meets Australian seekers too, pushing at the edges of knowledge and experience in our old/new continent, following the lure of snakes, of impossible distance, testing willpower, chancing death, meeting it. Seeking Aboriginal Australia, which we see through them, in approach, its dissolution and its survival, moments half-glimpsed. It is through Aster, the least attractive of his go-betweens, that we get to the point that joins the narrator’s journey to its beginnings. With this choice of companion, as well as the un-named road-worker they meet with, Rothwell challenges the strictures of thinking that are so pervasive in relation to Aboriginal Australia. No-one, no single group owns the paths of approach.

There is a beautiful resonance between what the narrator is given by the East German Haffner and what he is given, through Aster, from the old Aboriginal man called Tjampa. That will be for readers to discover. Why though, I wondered, is the narrator’s experience of Tjampa mediated through Aster, what is the significance of that? Rothwell’s Haffner provides something of an answer. Through years he has held on to a poor black and white reproduction of Raphael’s Sistine Madonna. The original was taken from its German home as part of the spoils of war. The reproduction serves to remind him of what it was to see the original: it was “to look on history”, “to be in a succession of a line of thought”. In Australia we live in the presence of a mind-expanding line of Aboriginal thought; we can see it only partially, but even this glimpse should keep us in mind of our privilege.

Kieran. Wonderfully written. Thank you.