Three day trek on foot to reach art centre: revise your definition of 'remote'!

1 May 2012

By KIERAN FINNANE

We’re used to the word ‘remote’ in Central Australia but try this for size: to reach the string of five art centres that make Omie Artists you must trek by foot for up to three days, often (for seven months of the year and then some) in torrential rain, across flooding rivers, clambering up muddy mountain sides and slithering down again. The company’s valiant manager, Brennan King, with six Omie security guards, necessary to protect him from attack by ‘rascals’ from the neighbouring tribe, make this journey several times a year. The artists’ work – among the last traditional barkcloths being produced in the world – has to be brought out the same way, rolled over PVC pipes and hoisted on the shoulders of the art centre coordinators.

How remarkable then for these works, steeped in the law and lore of the Omie tribe of Papua New Guinea and many of them a tour de force of design brilliance, to arrive on our doorstep here in the dry centre of Australia and to resonate so strongly with us.

How remarkable then for these works, steeped in the law and lore of the Omie tribe of Papua New Guinea and many of them a tour de force of design brilliance, to arrive on our doorstep here in the dry centre of Australia and to resonate so strongly with us.

This experience we owe to, apart from Omie Artists, RAFT Artspace in Alice Springs. Its curator Dallas Gold wants to take the pulse of contemporary art in our region (in its expanded definition) and give us a sense of its dynamism, diversity, achievement and promise. This is the third exciting show in a row at RAFT, following on from Tjala Artists’ Punu-ngura (From the trees) and Tobias Richardson’s My Life as Sculpture. The journey has taken us from Anangu homelands around Amata in the far north-west of South Australia via the itinerant and eclectic imagination of Richardson into the mountainous jungle of Omie territory, each stop opening up a window onto a world rich with beauty, ideas, observation and spirit.

The Omie are few in number, King says about 1800 according to a census done by the Omie themselves in 2009. Around 70 artists are producing barkcloths. They live in Oro province on the eastern side of the ‘tail’ of PNG, on the slopes of Mount Lamington, one the country’s most dangerous volcanoes which last erupted in 1951. With no motorised transport into their territory, they live close to a traditional, subsistence lifestyle. While their grandfathers, under the influence of missionaries, traded in coffee, peanuts and tobacco, carrying their crops to market, today selling their art is the Omie’s main source of cash (there are no state subsidies for art centres in PNG). According to King, the money is used to pay for medical services, Western clothing which they’ve been wearing since the 1970s, cooking pots, nails and construction tools, and batteries for torches. There are few other accessories of a Western lifestyle in their world, with the exception of some mobile phones. This is how the art centre coordinators, all of them Omie, communicate with King who is based in Sydney. To get signal they have to climb a mountain or at least a tree. Ingenious ‘bush mechanic’ systems keep the phones charged.

Now start to revise your definition of ‘remote’.

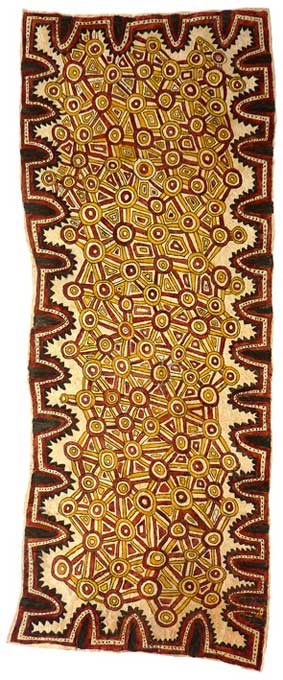

The Omie’s seclusion is part of the aura of the work on show at RAFT, imparted not just as an idea of geography, but in the very materials and time-honoured techniques with which they work. The bark (the inner skin) is cut from the trees growing on their mountains, rinsed in the waters of their fast-flowing streams and rivers, beaten with their mallets fashioned from black-palm wood. Their colours – including greys, ochres, reds, greens and blacks – come from the volcanic mud of Mount Lamington, from fruits, ferns and grasses and the detailed traditional knowledge that tells them where to find the source plants and how to extract the pigments. Their painting implements include the frayed husk of the betel nut, used to apply fill-in colour. Applique work is done with a needle made from bat-wing bone.

The Omie’s seclusion is part of the aura of the work on show at RAFT, imparted not just as an idea of geography, but in the very materials and time-honoured techniques with which they work. The bark (the inner skin) is cut from the trees growing on their mountains, rinsed in the waters of their fast-flowing streams and rivers, beaten with their mallets fashioned from black-palm wood. Their colours – including greys, ochres, reds, greens and blacks – come from the volcanic mud of Mount Lamington, from fruits, ferns and grasses and the detailed traditional knowledge that tells them where to find the source plants and how to extract the pigments. Their painting implements include the frayed husk of the betel nut, used to apply fill-in colour. Applique work is done with a needle made from bat-wing bone.

The barkcloth artists are all women. Omie men’s visual culture is expressed through tattoo art, the decoration of their bamboo smoking-pipes and chieftain’s staffs, and the creation of pig’s tusk necklaces and feather head-dresses.

The barkcloth artists are all women. Omie men’s visual culture is expressed through tattoo art, the decoration of their bamboo smoking-pipes and chieftain’s staffs, and the creation of pig’s tusk necklaces and feather head-dresses.

The barkcloth designs belong to separate clans, passed down from generation to generation through the female line. The sacred mountains and associated creation stories of Omie territory play a large part in what is visualised, but equally, homage is paid to the finest details of the natural world – the skin of the lips of a snake, the hipbones of a frog, the uncurling of fern fronds, the thorns of a vine.

Their own visual traditions are also replicated, particularly tattoo designs for both men and women.

Traditionally the barkcloths were made both for wearing, especially in ceremonies – and are still for this purpose – as well as for hanging in their dwellings. The works on show at RAFT have been made specifically for the art market.

The success of their exhibitions – the first took place in 2006 – has revitalised the barkcloth practice, according to King. Today young women in number are learning the designs and skills from their elders.

When you walk into the gallery there is an immediate association with Persian carpets, because of the intricacy of design and the tendency in many works to frame the design, an Omie aesthetic tradition, says King.

Up close the resonance of many designs with Aboriginal art of the desert is apparent. In some the commonality is astonishing. In particular Dapeni Jonevari’s Frog hipbones and Omie mountains looks like a classic Tingari painting, with its network of concentric circles inter-connected by straight lines. But it goes deeper than that. Our appreciation of the power of these works is enhanced by our education at the hands of Aboriginal artists – that what appear to be abstract patternings are charged with particular knowledge and spiritual force and that the works declare the artists’ profound connection to their land.

Pictured, from top: The entrance to this village’s art centre can be seen on the right. Staff quarters are in a similar building. All buildings are constructed from traditional materials with the exception of nails. The roofs are made from sago leaves. • Omie dance a welcome celebration for Brennan King’s arrival at their newest art centre in January 2010. • Pig tusks and teeth, and fern leaves by Linda-Grace Savari. • Frog hipbones and Omie mountains by Dapeni Jonevari. Photos courtesy Omie Artists.

Below: Omie Artists at RAFT Artspace in Alice Springs. Photo courtesy RAFT.