Suicide: a new and growing problem among NT Aborigines

18 August 2011

By KIERAN FINNANE

By KIERAN FINNANE

Suicide is a new and growing problem for Aboriginal people in the Northern Territory. The only detailed published study, looking at data from 1981 to 2002, shows that there was only one suicide by an Indigenous man in the NT in 1981, in contrast to seven that year by non-Indigenous men. In the 22 year period the first suicide by an Indigenous woman was not until 1991, while between one and three by non-Indigenous women had been recorded in every year since 1984 and four were recorded that year.

The study by Mary-Anne Measey, Shu Qin Li and Robert Parker was published in 2005 by the NT Department of Health and Community Services. It reports that the rate of suicide amongst men in the NT, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous, increased during the 1990s and early 2000s, while the Australian rate remained stable.

At the end of the study period the rate for Indigenous males began to increase sharply: in 2001 to 2002 it was approximately three times the comparable Australian rate, while the NT non-Indigenous male rate was approximately 1.6 times the Australian rate.

The rates among Indigenous women increased substantially from 1991 to become twice as high as the Australian female rate by 2001-2002. The rates among non-Indigenous women had been lower than the Australian female rate in the 1980s, and reached a similar level in the 1990s.

As we reported last week Independent MLA Alison Anderson has called for detailed recent data on suicides in the NT to be made available. She particularly wants to see the distribution across urban, rural and remote parts of the Territory.

Ms Anderson also asked for statistics on “how many Aboriginal kids actually come into Cowdy Ward and Ward One in Alice Springs with mental illness, paranoia and all the symptoms of psychosis”. She wants to know how many of these cases are related to the use of ganja (cannabis). This call is supported by Laurencia Grant, manager of Central Australia’s only dedicated suicide prevention program, the Life Promotion Program. Set up within government in 1998 in response to a high incidence of youth suicide, the program, while still funded by the government, is now auspiced by the NGO, the Mental Health Association of Central Australia (MHACA). Apart from Ms Grant, the program employs Brian Kennedy, Larissa Knight and Valda Napurrula Shannon.

Since 2001 Life Promotion, as part of its service agreement with the government, has kept a record of suicides in Central Australia (for this purpose, the NT area south of Elliott). The figures are based on police reports of deaths suspected to be suicides and some cases have yet to be officially deemed as such by the Coroner.

They show that from January 2001 to January 2011 there were 108 suicides in the region. The majority of them were male, Indigenous and aged over 25. Specifically, there were 79 Indigenous suicides compared to 29 non-Indigenous; 91 male to 17 female; 69 over 25 years of age to 39 under 25.

The majority occurred in the region’s major towns: 44 in Alice Springs and 17 in Tennant Creek. But the remote areas were over-represented with 47.

This year there have been six deaths by suicide in the Centre. As a number that looks much like recent years. For instance, last year by the end of August there had been eight deaths by suicide. However, the age distribution this year looks different: five out of the six have been under 25. All of the five have been Aboriginal and four out of the five were male. The deaths have also come in a cluster, with five occurring in the two months of July to August. One occurred in the Western Desert, one in the Pitjantjatjara lands, one in Alice Springs, one in the Barkly and one in Warlpiri country.

Preventing and containing possible clusters of suicides is one of the tasks that the Life Promotion team attempts. Acting on the concern that one suicide can put other people at risk, when the team receive police reports of a suspected death by suicide, they call an interagency response meeting. Those attending are members of the Life Promotion steering committee.

Says Ms Grant: “I try to provide everyone with as much accurate information as possible about what has happened. Sometimes this comes from people phoning in from the community affected.

“We try to identify family members, partners, children and other young people who may be at risk and to work out what the capacity for support is from every person in the room.

“We try to identify family members, partners, children and other young people who may be at risk and to work out what the capacity for support is from every person in the room.

“This response strategy has never been evaluated and for most people it goes beyond their job description, but it demonstrates a lot of good will and a recognition of combined responsibility.”

However, agency response can only go so far. Most often it is family and friends who are in the best position to prevent a suicide and a central focus of the Life Promotion Program is to better equip workers and other members of the community to respond.

Some headway had been made in this area with what is known as “gatekeeper training”, with the support of Lifeline in auspicing the Canadian program called Applied Suicide Intervention Skills Training (ASIST), which teaches people about recognising warning signs for suicide, how to respond to them and where to go to get further help.

Some new creative ideas seemed to be called for to adapt this style of training to the life realities of many Aboriginal people in Central Australia. These are being brought together by the Life Promotion Program under the heading of “Suicide Story”. This is a training package made up of short films, audio material, animation, artwork and activities, all designed to get Aboriginal people talking about suicide, understanding why it has become a problem in Aboriginal communities, some of the cultural beliefs around suicide, and what they can do to respond to both serious concerns and common threats of suicide.

Ms Grant says threats can be thrown around pretty freely in order to get things that the person wants and at times are a form of domestic violence though they can be acted upon impulsively and irredeemably. They confuse the issue of suicide and the behaviour is worrying for the person or family on the receiving end.

So far the training has been trialled in Tennant Creek, Yuendumu, Hermannsburg, Numbulwar (off Groote Eylandt), Alice Springs, Mutitjulu and Ali Curung. Life Promotion have now received funding for two years from the federal Department of Health and Aging to extend the training.

Ms Grant says it has been particularly valuable for the program to be able to employ Aboriginal people to help deliver the training. Valda Napurrula Shannon, based in Tennant Creek, has developed a program activity around fire, which has such a central role in Aboriginal life. Participants are asked to identify the things in life that feed a person’s inner fire, that keep them going each day, and the things that can cause a person’s fire to die down and what needs to be done to re-stoke that fire.

Ms Grant says the activity is very effective, easy to do and Life Promotion has been approached by other organisations to train their workers using this tool.

Causes

No-one would doubt that each suicide has its own complexity, but there are some common associated factors and patterns.

The 2005 study of suicide in the NT, extracted information from the Coroner’s files over three years from 2000 to 2002.

During that time Indigenous people accounted for 45% of the NT deaths by suicide. Three-quarters of all deaths by suicide occurred in the Top End and the following figures all relate to Top End data.

Demographic risk factors appeared to be: marital status (63% of suicides were by single, widowed, divorced or separated people); employment status (41% were unemployed); and occupation (56% were involved in physical work).

Associated risk factors appeared to be: alcohol or other drug use (56% at time of death, 72% around or prior to time of death); depression or other mental illness (49% had such a diagnosis); relationship problems (25%).

For the majority (61%) there was more than one factor present.

Relationship problems were the most common associated factor for younger people; alcohol, for those aged 35 and over.

Males accounted for 85% of all suicides, with the most common associated factor being alcohol, followed by relationship problems.

The study also found that only one third of the people who had committed suicide had had contact with a health service provider in the previous 12 months.

Lifeline – 13 11 14

Beyond Blue – www.beyondblue.org.au

Reach Out – www.reachout.com.au

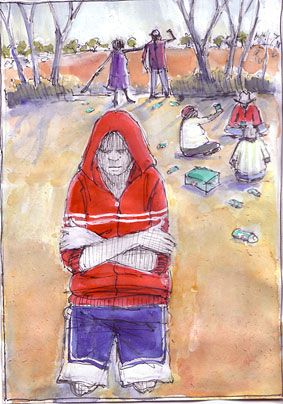

PHOTOS: Top – feeling unloved. Centre – hearing voices. Drawings by Sue McLeod for “Suicide Story”. Below – Suicide Story training for Pitjanjatjara people held at the college in Yulara in May 2011. Laurencia Grant kneeling at the front, far left.

A very good article and highlights the fact that something is seriously wrong and needs to be addressed. Among the alcohol and cannabis issues there is no doubt that strong families are also the key to addressing the problem.

Relying on alcohol for the self medication of mental health problems, coping with abusive disfunctional relationships, subsisting in a harsh environment that offers little opportunity for personal development or gainful employment, culturally alienated from the old and new worlds, disconnected from the mainstream, feeling hopelessly overwhelmed by practical realities, wallowing in thoughts and emotions, uncared for and uncaring … why is anyone surprised people choose death.

Our grip on life is fragile and for those battered by brutal reality, the sensitive souls or damaged minds, there is little respite beyond drugs.

It’s good to see Ms. Grant’s Life Protection team out there trying to re-stoke the fires, offering practical assistance to at risk individuals and devastated communities.

Overcoming the environmental factors, the physical and historical realities, the personal issues is a huge, unenviable challenge.

You can’t create resilient communities with alcohol, and the jury is still out on the pharmaceuticals. Do they actually work or create more mental instability?

The MDMA family (eccy’s) can help generate loving feelings and I personally don’t find cannabis nearly so lethal or disabling.

Life is often made bearable, comical, laughable and inconsequential with a big smokey toke on an attitude adjuster.

cheers,

Michele

Byron Shire, NSW.

[ED – Cannabis is illegal. The Alice Springs News is publishing this comment under the principle of freedom of speech.]